AARAKSHAN

(“reservation”) 2011, Hindi, 164 minutes

directed by Prakash Jha

produced by Firoz A. Nadiadwala; story by Kamlesh Pandey; associate script writer: Ravinder Randhawa; screenplay: Prakash Jha, Anjum Rajabali; dialogue: Prakash Jha; choreography: Jayesh Pradhan; art director: Jayant Deshmukh; costumes: Priyanka Mundada; lyrics: Prasoon Joshi; music: Shankar, Ehsaan, Loy; cinematography: Sachin Krishn

|

Prakash Jha’s AARAKSHAN takes one of the most controversial and divisive political and social issues in post-Independence India—the government’s industrial-strength affirmative-action policy of “reserving” a substantial percentage of bureaucratic posts and “seats” in government-sponsored educational institutions for historically disadvantaged groups—and intermarries it with industrial-strength and star-power-driven Bombay melodrama. This is an audacious miscegenation in a cinema that generally avoids even the mention of caste, and though the results are uneven—a predictably emotion-dripping and sometimes saccharine story, enacted amid glossy sets and well-tidied locations (mostly in and around Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, which looks terrific here), with larger-than-life heroes and villains and a much-too-tidy conclusion—the effort is commendable and, in a few standout sequences, the dialog powerfully evokes some of the raw emotions, deep-seated prejudices, and real dilemmas in which the reservation issue is enmeshed. Jha likes to engage with modern Indian life in a semi-realist mode, as he did in his 2010 film RAAJNEETI (“politics”), which grafted the ancient Mahabharata’s tale of sanguine intra-familial rivalry onto the fortunes of a contemporary political dynasty that sometimes deliberately evoked the charismatic and tragic Nehru-Gandhi clan. But that film consisted largely of a succession of grandiose set pieces, with only minimal (and, perhaps because Mahabharata-inspired) rather uniformly distasteful character development. In AARAKSHAN, Jha takes it slower, crafts more complex and sympathetic characters, and allows for some extended and dramatic (if rather declamatory) exchanges. |

|

|

|

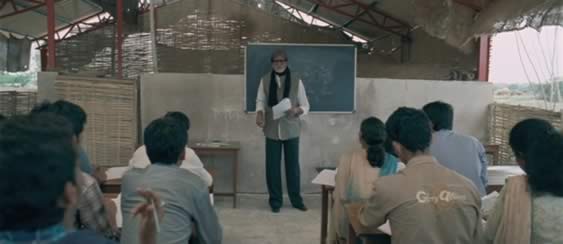

Amitabh Bachchan plays Dr. Prabhakar Anand, a mathematician and the principal of an illustrious private educational institution, STM college, whose reputation he maintains through high and scrupulously fair standards. He gives employment to his meritorious protégé, a physics teacher named Deepak Kumar (Saif Ali Khan), though other faculty members cruelly imply that Kumar is only there because of the “reservation quota” that favors him as a Dalit (“oppressed,” the term now preferred by many for caste groups formerly labeled “untouchable,” “scheduled caste,” and “Harijan,” as well as by numerous occupational and usually pejorative names). Kumar romances Dr. Anand’s daughter, Poorbi (Deepika Padukone), even as he plans to pursue a Ph.D. degree in the US. A workaholic social servant, Dr. Anand devotes much of his time outside school to offering free tutoring in math to poor children, including Muniya (Aanchal Munja), the daughter of Shambhu (Yashpal Sharma), a local dairyman of the Yadav caste (a large caste group in northern and central India officially classified among the “OBCs” or “Other Backward Classes” who are also eligible for special affirmative-action initiatives). The harmony of the college is marred by Mithilesh Singh (Manoj Bajpayee; the character’s surname, in this context, suggests feudal landlord caste status), a wavy-haired academic entrepreneur who supplements his teacher’s salary with income from a chain of highly-successful “coaching centers” that charge high fees to prep students for India’s all-decisive exams. In this, he is in league with the sleazy state Education Minister, Baburam (Saurabh Shukla), who seeks to install Singh in Dr. Anand’s position after the latter refuses to bend the rules and grant admission to Baburam’s low-scoring nephew. Baburam and Singh get their chance in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s 2008 decision upholding the Mandal Commission’s recommendation that 27% of places in government-sponsored educational institutions be reserved for OBCs (in addition to the 22.5% quota already set aside for “Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes”). College life is disrupted by the controversy, and Dr. Anand is quoted in the press supporting the policy as a way of correcting historical injustices. When the STM College board of directors demands that he retract his statement, Anand resigns in protest. Not content with this, Singh and his cronies embark on a campaign to ruin him completely, maligning his reputation and managing to evict his family from their recently-built private home, which has, with cruel irony, been transformed into one of Singh’s “K.K. Coaching Centers.” The ex-principal takes shelter with his cowherd friend, and, refusing to be defeated, sets up a free academy amidst the lowing buffalo of the dairyman’s tabela or cowshed. Here he is soon joined by Kumar, who gives up a cushy graduate fellowship at Cornell when he learns of the turn in his mentor’s fortunes, but who runs afoul of the local police (who are, of course, in the pocket of Baburam and Singh) when he stages a one-man attack on the offending coaching center. Dr. Anand’s woes multiply—but so do (pun intended) his underprivileged math students, who turn out to ace the qualifying exams, upstaging their expensively-coached middle-class peers. At this point, the evil cabal that now controls STM decides that Dr. Anand and his upstart school must be annihilated.

|

|

Bachchan’s performance, strong overall (it was nominated for a Filmfare “Best Actor” award) is at its most affecting in moments when he is subdued and nearly broken, rather than when he is loudly declaiming about his siddhant (“principles”). Saif Ali Khan, more commonly seen as a hunky heartthrob, does a commendable job as a bookish physics teacher prone to occasional bursts of righteous rage. His eloquent and angry speech in defense of reservations, following the vandalizing of the college cafeteria by a group of low-caste workers, is one of the film’s most powerful moments. His casting was assailed by some Dalit activists, however, since his family background, albeit non-conventional (his father was a Muslim Nawab turned cricket pro, and his mother, actress Sharmila Tagore, hails from the most illustrious Brahman clan in Bengal) places him squarely in two elites. Deepika Padukone looks young enough to be a college student in love with her teacher, and is, as usual, gorgeous. There are no memorable songs (on the contrary, the embarrassing Mauka “[Give me a] chance!,” sung by Kumar and a low-caste chorus with full-blown “Bollywood” choreography, is utterly dispensable and best forgotten), and the film’s feel-good ending, if perhaps rather beside the point (and after its several good points have repeatedly been made), can only be called a disappointment. Jha invokes (literally) devi-ex-machina, bringing the school’s mysterious founder and patron, Shakuntala Devi (Hema Malini in a beatific cameo), abruptly back from the Himalayan ashram to which she had retired decades earlier, to intervene to prevent the imminent destruction of All That Is Good—which she does simply through a few-second cell-phone call to an even higher-level politico than the Bad Guys were able to invoke—the state’s Chief Minister (and, evidently, her lackey). Instantly, machine guns droop, riot-geared police turn into genuflecting peons, and heartless officials tearfully beg forgiveness. That central yet problematic and contested Indian concept, dharma (“righteousness,” “morality,” among many other meanings), threatened by the forces of a-dharma, is upheld, in other words, through another equally problematic and ubiquitous subcontinental notion: sifaarish (“influence” or “clout”).

|

|

[The T-Series DVD of Aarakshan has good image quality and provides subtitles for both dialog and songs.]