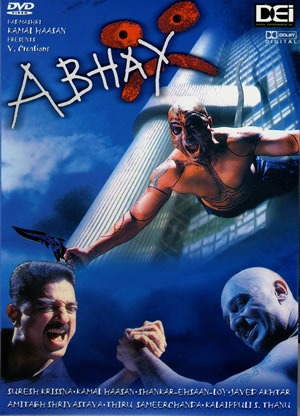

ABHAY

(“Fearless,” 2001, Hindi; also available in Tamil as AALAVANDAAN)

Directed by Suresh Krissna

Story and screenplay: Kamal Haasan

Music: Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy and Mahesh; Lyrics and poems: Javed Akhtar; Dialogue: Amitabh Srivastava; Cinematography: S. Tirru

Celebrated Tamil actor and screenwriter/director Kamal Haasan’s newest tour-de-force is visually astonishing, dramatically unrelenting, and emotionally disturbing — a rollercoaster ride over the ravaged terrain of the dark side of the human soul. Haasan has explored such territory before, in films ranging from relatively mainstream (1993’s MAHANADI) to wildly maverick (2000’s HEY RAM). ABHAY tries to be both, and though initial media reports suggest that the balancing act may not be successful in terms of the bottom line, the effect of the film’s marriage of a highly intelligent imagination with tried-and-true narrative themes certainly offers viewers an extraordinary experience: something like a South Indian folktale seen through the darkened glasses of Freud and Foucault and clad in the logo-imprinted garb of fin-de-siecle global consumerism and mass-mediated entertainment.

The basic story develops yet another variation on the now-classic theme of two brothers on opposite sides of the law (cf. MOTHER INDIA, DEEWAR, GANGA JAMUNA). Here Vijay Kumar (his first name, meaning “victory,” echoes early Amitabh Bachchan roles) is the much-decorated leader of an Indian-army SWAT team charged with flushing out terrorists; his twin brother Abhay (“fearless,” and likewise aptly named) is a schizophrenic accused of the childhood murder of his stepmother and confined to an asylum for the criminally insane. Both roles are played by Haasan, and the double impersonation is pursued with extraordinary zeal; the actor shaved his head and bulked up for the lunatic brother, whose scenes were shot a month behind those of the trimmer army commando. Abhay is the “heavy” of the duo in more ways than one; his voice is deeper, his gait more ponderous, his violence more gratuitous (or is it? — this assumption is briefly but perhaps importantly questioned near the film’s climax), and his overall persona more authoritative and interesting. By film’s end he has acquired the surreal aura of a sort of monster shaman and living transformer-superhero. The effect, through digital magic, of seeing the twins together is properly spooky, and the dual portrayal offers another consummate performance from an actor already renowned for multiple roles and disguises.

Trouble develops when Vijay brings his pregnant fiancée, news anchor Tejaswini (Raveena Tandon) to the asylum to meet Abhay, and the sight of her begins reopening the secret of the twins’ past — a tragic childhood of neglect and abuse that culminated in Abhay’s murderous act. Taking Tejaswini to be his reborn stepmother, Abhay resolves to “save” his brother from her clutches; his predictable method of doing so involves a wholly unpredictable and very suspenseful sequence of stratagems and coincidences. Along the way, he meets (and generally mangles) security guards, psychopaths, drug addicts, middle-class burghers, lots of cars and trucks, and one substance-abusing popstar, Sharmilee (Manisha Koirala), who performs in an eye-popping song and dance sequence (Cheete ki chaal) that seemingly sends up “worldbeat” and THE LION KING. Meanwhile the camera does its best to get inside Abhay’s hallucinating head, aided by state-of-the-art digital effects and stunningly surreal sets. The effect is often spectacular, as when Abhay wanders through a postmodern Delhiscape that blends the bazaar picturesque with the consumer detritus of multinational capitalism (with its corporate logo-lenders presumably paying for their on-camera time?). Though the digital magic always retains something of a dark and jagged edge, this Abhay-in-Wonderland sequence helps build viewers’ empathy for his arrested, childlike personality, even as they witness his gory, video-game-like rampages.

Although the barrage of special effects may at times appear gratuitous, closer examination reveals little here that has not been positioned by a meticulous directorial vision. Allusions to other films, both Indian and Western, are rampant and seemingly deliberate: they offer parody in the technical, non-ridiculing sense (as in musicology) — of intentional improvisational quotation and elaboration. Haasan clearly has his eye on both DEEWAR and SHOLAY (a recurring coin-toss motif is used to great effect), and also on Hitchcock’s PSYCHO, and the more recent hits DIEHARD, TERMINATOR, and SILENCE OF THE LAMBS. There’s a brief but inspired homage to Chaplin, and bouts of animation modeled on Saturday-morning TV superheroes. The live actors’ own fights suggest the cartoon-like antics of World Wrestling Federation superstars.

There is, in short, much to admire — even to marvel at — in this carefully crafted film, especially when one compares it to some other stylish but vacuous efforts (e.g., an ill-plotted, would-be psychological thriller like AKS). But this being so, it is appropriate to ask where a film that packs so much stunning visual baggage is finally taking us. Since its second half is dominated by a grim saga of child abuse (one that is marred, unfortunately, by a misogynistic and conventional double standard that ultimately redeems a drunken and brutalizing father while condemning his equally-abusive 2nd wife as an irredeemable churail or witch, and also by a pretty but tritely exoticizing cameo of the Todas, a tribal people of the Nilgiri Hills), one obvious message of the film is that children tend to imitate what they see — and go on reproducing it as adults. This suggests a curious, even ingenuous auto-critique of the bloody spectacle that super-saturates the film — a film, indeed, that one must hope small children are not permitted to watch. It also suggests the darkest possible reading of its own “happy” ending, and of its presumed prognosis for the future of its characters (and the world?): that decorated-hero Vijay may turn out to be more like his father and twin brother than he (or we) would like to believe, and that the endemic and explosive violence that has itself become another trademark of late-capitalist entertainment — an expression of the animal within us that is never altogether tamed by socialization, and that is also selectively fostered by the agency of the state — may be destined to replay and parody itself endlessly in the global hall of mirrors. Clearly, this is not a feel-good conclusion, so why is it all so good to watch? If Haasan meant to leave us with this dilemma, then he is even smarter than he appears.