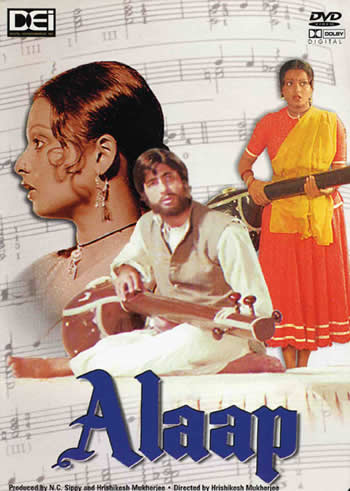

ALAAP

(“Prelude,” Hindi, 1977)

Directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Produced by N. C. Sippy

Story idea: Harindranath Chattopadhyaya, Hrishikesh Mukherjee; Screenplay: Bimal Dutta; Dialogue and lyrics: Dr. Rahi Masoom Reza (“Koi gata” by Harbansraj Bachchan); Music: Jaidev; Cinematography: Jawant R. Pathare; Art direction: Ajit Banerjee; Playback: Lata Mangeshkar, Yesudas, Kum Faiyyaz, Asrani, Madhurani, Bhupendra, Dilraj Kaur, Ustad Bade Gulam Ali Khan

Dedicated to the memory of the great singers K. L. Saigal and Mukesh, this charming and unpretentious film offers a palate-cleansing change from the spicy “masala” epics that dominated its era, and features their superstar Amitabh Bachchan in a decidedly offbeat role. Though its central themes of protracted father-son conflict and of a suffering artist in a callous world are routine enough, its comparatively realistic depiction of life at various social levels in a provincial town, witty yet understated dialogues and beautiful songs that are deftly integrated into the storyline, and masterful but low-key performances all serve to lift it above the ordinary.

As the film opens, Alok (Amitabh Bachchan) completes a degree in classical music and returns to his hometown where he promptly reconnects with a childhood friend, the spirited horsecart driver Ganeshi (comedian Asrani, who played the Hitler-esque jailer in SHOLAY), who entertains him enroute home with a comic folk-style song to his mare (Binti sun le, “Hear my plea…”). Back at the prosperous family home, Alok is reunited with his adored sister-in-law (Lily Chakraborty) and elder brother Ashok, but soon runs afoul of their dictatorial father Triloki Prasad (Om Prakash). Alok calls his old man “Herr Hitler,” and with good reason, for he exemplifies the petty tyrant-in-his-own-domain mentality of certain upper-class men, who tyrannize their families and express their “feelings” only through tersely barked commands. Papa peremptorily informs Alok that he must now abandon the silliness of music and join his brother in the family law office. After a humorous nighttime song in which Alok assumes a barrister’s role and pleads the moon’s case to his sister-in-law, he accompanies his brother to town, but plays hooky from the family firm to visit Ganeshi’s modest home. In an adjacent building, he finds a singing lesson in progress, taught by a retired courtesan of Banaras, Sarjubai (Chhaya Devi); the pupil is Ganeshi’s sister Radhika Prasad, nicknamed Radhiya (Rekha). Sarjubai’s devoted male companion, known simply as “Maharaj” (Manmohan Krishna), plays percussion.

After a prickly initial exchange with the grand old lady, Alok wins her heart and is accepted as a pupil, much to his own and Ganeshi’s delight; Radhiya too is secretly pleased. He also learns of Sarjubai’s relationship, long ago, with a heartbroken Raja (Sanjeev Kumar), which leads to the song Ayi ritu saavan ki (“the season of rains has come”).

Alas, Triloki Prasad soon comes to know that his son is consorting with “useless riff-raff”—people who drive tongas and smoke beedies—and flies into a rage, both because of Alok’s disobedience of his order and because he himself is running for the Chairmanship of the Municipal Corporation (the equivalent of Mayor) and he will not have the family honor besmirched (there is a nice vignette here of him plotting caste-bloc politics with a couple of cronies—a true slice-of-life). He soon takes up the court case of a scheming merchant who is seeking to have old Sarjubai and her neighbors evicted, and he also tries to arrange Alok’s marriage with the merchant’s spirited daughter Sulakshana (Farida Jalal), but luckily she already has a lover, one Kishen. Triloki Prasad triumphs in court and Sarjubai loses the home she had purchased with a lifetime of savings; Alok is furious and uses the money his triumphant father has given him for buying a car to instead purchase a horsecart with which to earn an honest living: thus he will daily shame his stiff-necked father and live in sympathy with the humble people he has come to love and whom his father seeks to destroy.

Given that both baap and beta (father and son) display similar rigidity of character, Alok’s life goes steadily downhill from here on, despite his eventual marriage (requested by Sarjubai) to the devoted Radhiya and, in time, the birth of a son to the couple. Several attempts by his wife, sister-in-law, and brother to patch things up with the perpetually fuming Triloki Prasad come to nought, and it takes Alok’s own fading health (like many a rickshaw driver, he contracts tuberculosis), and a visit from the now aged Raja, to make the scales fall from the old man’s eyes. Too late, though: Alok’s melancholy final song Koi gata, main so jata (“Someone sings, as I fall asleep,” penned by Bachchan’s real-life father, poet Harbansraj Bachchan) sounds like an elegy for both him and Sarjubai.

Although Rekha gives a fine and understated performance as Alok’s adoring and long-suffering wife, romance of the usual sort is downplayed here, and the strongest female character is in fact the aging courtesan-singer Sarjubai, wonderfully portrayed by Chhaya Devi. Though she gradually assumes the role of Alok’s lost mother, she never lapses into the pious maternal stereotypes common to so many Bombay films, but instead offers a complex and rare portrait of an earthy, mature, and experienced woman who has both loved and suffered deeply. She thus adds a further dimension to the history of portrayal of courtesans and professional women in mainstream cinema (cf. BHUMIKA, PAKEEZAH, UMRAO JAN), and even though few specific details of her life are provided, we sense the extent of her experience and of her independence of spirit, and we feel that we know her deeply by the film’s end. It is she, with her surrogate but deeply devoted family, who is the real antithesis of the selfish and self-righteous Triloki Prasad, who gradually cuts himself off from all his near and dear kin.

[The DEI DVD of this charming film features a superior quality print, though it is marred by a tendency for the image to move up and down during the first few scenes— as if the frames were slipping out of alignment (didn’t anybody check on this?). Though a bit irritating, this undesirable feature does not persist and is not enough to spoil viewing. Subtitles, though not provided for the many songs, are generally good, however they mistakenly call Ganeshi’s sister “Raziya” (a Muslim name!).]