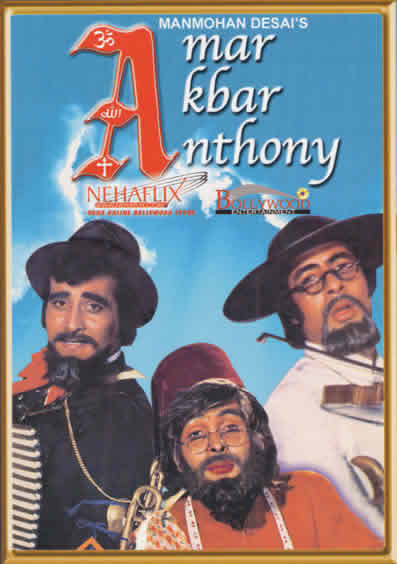

AMAR, AKBAR, ANTHONY

(Hindi, 1977, 174 minutes)

Produced and Directed by Manmohan Desai

Released by M. K. D. Films

Story idea: Pushp Raj Sharma; Story: Mrs. J. M. Desai; Screenplay: Prayag Raj; Scenario: K. K. Shukla; Dialogue: Kader Khan; Art Director: A. Rangraj; Editing: Kamalakar; Director of Photography: Peter Pereira; Lyrics: Anand Bakshi; Music: Laxmikant, Pyarelal

This robustly entertaining and enduringly popular film offers the first full display of what would become the classic features of a Manmohan Desai masalablockbuster: a star-studded cast featuring three pairs of heroes and heroines, a fiendishly-complex two-generation-spanning plot involving tragic separations and miraculous reunions, a spectacularly-suffering Mother (usually played by Nirupa Roy), a fast-paced alternation of emotionally-distinct, semi-autonomous episodes (which Desai termed “items”) that run the gamut from tragedy to action-adventure to romance to slapstick, and a heavy handed yet simultaneously self-parodic invocation of popular religious and patriotic symbols. These are already signaled by the title’s alliterative trinity of Sanskrit, Arabic, and English personal names, signaling (in properly descending demographic order) the Hindu, Muslim, and Christian communities whose essential unity and harmony—within the copious bosom of a (visibly Hindu) Mother India—is one of the film’s (and Desai’s personal favorite) themes. Here it is reaffirmed through the (literal) blood brotherhood of the male protagonists.

As the film opens, a chauffeur named Kishenlal (Pran) is released from prison after serving a sentence for a hit and run accident. He returns home to find his wife, Bharati (Nirupa Roy)—whose name evokes the nation’s—suffering from tuberculosis, and their three little sons starving. He is furious to learn that his rich employer Robert has not honored his promise to support the family, for indeed (we soon discover) Kishenlal himself was innocent of any wrong, but took the rap for an accidental killing at the guilty Robert’s request, on condition that his family receive triple his wages during his jail sentence. When he confronts the villain in his lair (played as a comical Anglo-Indian by Jeevan, the actor famous for portraying the mischievous sage Narada in numerous mythological films – cf. JAI SANTOSHI MAA), Robert first humiliates him and then orders him killed by his goons, but Kishenlal escapes in a car that (unbeknownst to him) is loaded with smuggled gold bullion. He returns home to discover his sons abandoned by Bharati, who has left a suicide note (as she doesn’t want him to have to spend money on her T.B. treatment). Since Robert’s men are in hot pursuit, he loads the boys into a car and rushes them to a nearby park where he leaves them under a statue of Mahatma Gandhi—incidentally, it happens to be August 15th (Indian independence day). Before Kishenlal can get back to them, the little boys get accidentally “partitioned” and are found and adopted by (respectively) a Hindu police officer, a Muslim tailor, and a Catholic priest. At the same time, Bharati, running through the forest, is struck by a falling tree limb and loses her eyesight, and Kishenlal is apparently killed in a fiery car crash. But no!—the latter survives, and even gets away with the gold, though a police constable mistakenly reports to poor, blind Bharati (who has now decided to live, enduring blindness as God’s punishment for her suicidal impulse), that he and their sons have all perished. Haay!!

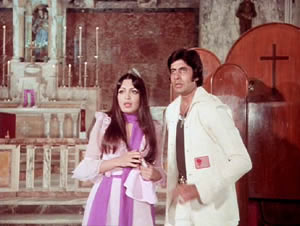

Fast forward twenty-two years: the middle son is now a streetsmart Goanesque liquor dealer named Anthony Gonsalves (Amitabh Bachchan), who exasperates his priestly benefactor but atones for his waywardness by giving half his earnings to the Blessed Virgin. Amar (Vinod Khanna) has followed in the footsteps of his adoptive father to become a dashing and exemplary (which is to say, tough) police officer, and Akbar (Rishi Kapoor) is a passionate qawwali singer in love with a young doctor named Salma (Neetu Singh). All are going about their business when an old, blind woman who sells flowers on the street (take a wild guess as to who she is!) is struck by a car, and the three boys, who turn out to share her bloodtype, are pressed into service as donors. In one of the film’s most memorably overdetermined visuals, this is done by direct transfusion from three beds positioned under windows that frame (respectively) a temple, a mosque, and a church, while “Mother India” lies unconscious on a fourth bed at the boys’ feet.

Although this may sound like the grand finale to an epic film, it is in fact only the end of the 25-minute prologue to this one: the credits roll as the boys placidly give their blood to the poor maternal “stranger.” The remaining two-and-a-half hours will naturally be devoted to contriving, but artfully delaying, the revelation of who is who, reuniting the sundered family, and giving the evil Robert his just deserts. But since all this is a foregone conclusion, most of viewers’ attention can be surrendered to the cavalcade of “items,” including love interest (of suitable religio-ethnicity) for each of the boys, knockabout brawls and car chases, Bachchan’s Bombay-mod wardrobe, zippy dialog spiced with plenty of street slang, and a hilarious final triple impersonation.

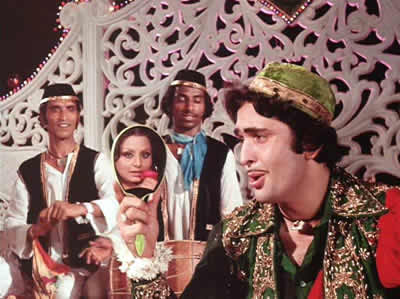

The bouncy Akbar Illahabadi, King of Qawwals, is the first to fall in love, wooing his beloved Salma during a public performance of the rousing and suggestive filmi qawwali Parda hai parda (“There is a veil”):

There is a veil, and behind the veil,

a modestly veiled woman,

and if I don’t unveil her,

then my name isn’t Akbar!

But when Salma’s strict and dwarfish lumber dealer father forbids their union, Akbar rounds up a group of transvestite hijras (the real thing, from the looks of them) to taunt him with the song Tayyab Ali pyaar ka dushman (“Tayyab Ali is the enemy of love!”). Overcoming his enmity will require a minor subplot involving an angry courtesan (the father’s ex-mistress) who sets the house on fire, allowing Akbar to display his courage by rescuing both Salma and her dad.

Officer Amar gets (for reasons to be discussed below) the most cursory romantic treatment: he apprehends a stylish young woman named Lakshmi (Shabana Azmi) who is hitching rides with strangers and then delivering them to a gang of robbers; however, we soon learn that she is only doing this at the behest of an evil stepmother (the famous actress Nadira in a cameo) who is threatening her beloved grandma. In a trice the stepmom and her dastardly gang are behind bars and Lakshmi shifts to the kindly Amar’s house, to henceforth be seen only in saris and with properly tied-back hair, engaged in virtuous activities such as taking in the laundry. She is, in short, well on her way to becoming a good, middle-class Hindu wife. No further surprises here.

Anthony falls, after a suitable buildup, for a London-returned knockout named Jennie (Parveen Babi), who attends the same church that he does and is ostensibly the daughter of Kishenlal (remember him? the boys’ actual father, who got away with a box of gold). The latter—thinking his wife dead and his sons irretrievably lost—has now become a crime boss himself and is getting back at Robert, who has been reduced to working for him. But in fact, Jennie is actually Robert’s daughter, whom Kishenlal kidnapped as part of his revenge, and when Robert escapes from Kishenlal’s surveillance and reestablishes himself as a rival smuggler king (this happens in a matter of minutes), getting her back becomes his number one priority, a task at which he is assisted by a ridiculous platform-soled strongman named Zebisco (Hercules). But first Anthony declares his love to Jennie during a rock’n roll Easter function (those Christians sure know how to party!) at which he emerges, top-hatted and monocled, out of an enormous Easter egg to perform the comical song My name is Anthony Gonsalves, which sends up all the pretensions (including rapid-fire but nonsensical English declamation) of certain Anglo-Indians: a cabaret version, one might say, of G. V. Desani’s novel All About H. Hatterr.

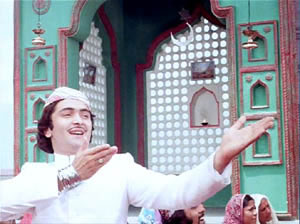

Poor blind Bharati stumbles in and out of these episodes, for she is now in contact with all three boys, though she does not yet realize that they are her own sons (of course, they touchingly call her “Ma” anyhow, as is quite proper in Hindi). Causing the scales to fall from everyone’s eyes will require intervention by Higher Powers, represented by suitably folksy deities of the three traditions: Santoshi Ma, Sai Baba (an early 20th century Muslim holy man who is now revered by many Hindus as well), and Jesus-and-Mary—assisted by cobras, a magical locket, and a bleeding crucifix. The pop qawwali-bhajan Shirdiwale Sai Baba (“O Sai Baba of Shirdi”), performed by Akbar and an ecstatic congregation in a shrine incorporating the Muslim crescent and star and a Shiva bull and lingam epitomizes this unembarrassed syncretism.

As the above synopsis should suggest, India’s religio-ethnic minorities are hospitably and centrally accommodated in this film, yet they are also presented (as American minorities have often been in Hollywood films) as embodiments of rakish comedy, exotic color, proletarian uninhibitedness, and yes, rhythm. Naturally they are junior brothers (who are traditionally permitted more license in the joint family), and moreover they are reassuringly Hindu inside (indeed, of one blood with Amar and the Mother, and as the voiceover song intones during the transfusion scene, “Blood is ever blood, never water.”) But as juniors and Others, they get to display the boisterous highjinks that would be inappropriate in their Senior, the grave patriarch-in-the-making Amar, who serves as the dharma-devoted Rama of this set, and whose most emotional scene occurs (naturally) when he recognizes and embraces their father. As a police officer (back when police officers were still routinely portrayed as incorruptible), he also represents the “dignity” of both the State and the middle class (and it seems appropriate that he is played by actor Khanna, who—after a flirtation with the Rajneesh movement—would eventually end up as a Hindu-nationalist Member of Parliament). Hence when it comes to a fistfight between Amar and Anthony, viewers will not be surprised to find the great and lanky Amitabh for once taking a beating; even if he is an inch shorter, Big Brother has to win. But despite their (necessary) weakness, minorities are clearly the spice of life in Desai’s worldview, and tellingly, the straight-laced Amar is the only brother who doesn’t get a song of his own, merely participating in show-stopping ensemble pieces: the triple-duet Humko tumse (“I’ve fallen in love with you”)—a lovesong uniting all three brothers and their sweethearts in separate locations, and featuring the voices of Lata Mangeshkar, Mohamed Rafi, Kishore Kumar, and Mukesh—and the final title-song trio (in which he gets to comically impersonate a one-man wedding band), when the bad guys get their comeuppance.

[The film is available in at least two DVDs, one distributed by Baba Traders (unseen by this reviewer), and one by Bollywood Entertainment. The latter is of decent, though not exceptional, quality. English subtitles are unfortunately not provided for the film’s seven songs.]