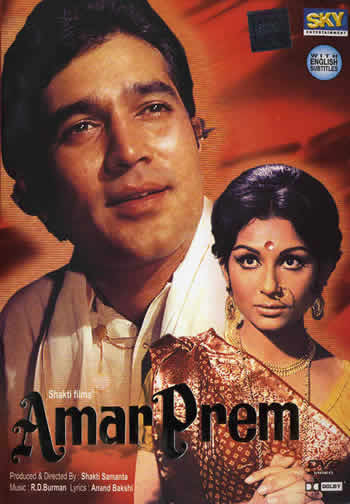

AMAR PREM

(“immortal love”)

Hindi, 1971, ca. 180 minutes.

Produced and directed by Shakti Samanta

Story: Bibhuti Bhushan Banerji; Screenplay: Aravinda Mukherji; Dialogue: Ramesh Pant; Cinematography: Aloke Dasgupta; Editor: Govind Dalwadi; Art Director: Shanti Das; Playback: S. D. Burman, Lata Mangeshkar, Kishore Kumar; Lyrics: Anand Bakshi; Music: R. D. Burman

Like its Samanta-directed, Khanna and Tagore-starring predecessor ARADHANA (1969), this is a weepy but moving paean to feminine suffering and self-sacrifice. Apart from its strong Burman-Bakshi score, it seems notable mainly for its semi-realistic depiction of the tribulations of a young woman forced into prostitution after fleeing an abusive marriage, and for its lighthearted vignettes of the Calcutta red light district (including prostitutes chomping on pani puriswhile gushing over Dev Anand films). The heroine Pushpa (Sharmila Tagore), whose days are chastely spent in puja and in wistfully gazing at the neighbors’ children, passes her evenings dutifully dispensing liquor and snacks to her whimsical patron Anand (Rajesh Khanna, here projecting a toned-down version of the suffering-optimist character he played in the 1970 film of that name), but any overt suggestion of a carnal relationship between them is discretely avoided. Nevertheless, Pushpa experiences the full social opprobrium of the “fallen woman” and suffers accordingly—and lengthily and spectacularly—until even her harshest critics must recognize her as an embodiment of “immortal love.”

As the film opens and credits roll, a young and tearful Pushpa stealthily flees her in-laws’ village to the ironic accompaniment of a folkish song (Doli men bithaike, “seated in a palanquin,” sung by the composer’s celebrated father S. D. Burman) that recounts the arrival and myriad hopes of a new bride. We soon learn that, because of her failure to conceive, Pushpa’s husband has married a second time and taken to beating her with a burning stick, scarring her back. But when a child’s false report that she exchanged sexual favors for money turns her maternal village neighbors against her as well, leading even her widowed mother to denounce her as a whore (kulta), Pushpa has no recourse but to accept the offer of a prosperous but leering and snuff-addicted local grandee, Nepal Chacha, to work in his palatial “home” in Calcutta.

This proves to be, of course, a brothel, albeit dubbed a “music school” and presided over by the kindly-looking Mausi (“Aunty,” Leela Mishra). Here Pushpa’s chaste and plaintive voice attracts the attention of Anand Babu, a refined and world-weary business executive who hides his personal sorrows (occasioned, as we later learn, by a socialite wife who doesn’t appreciate him and is uninterested in conjugal life or childbearing) in jocular philosophizing and nightly drinking bouts. Naturally, he has stumbled into the Quarter only by accident and is at first properly repelled by its raffish denizens, but Pushpa’s opening song Raina biti jaaye (“night has passed…[and my dark one has not come],” a sensual-yet-devotional lyric in which she assumes the voice of Krishna’s beloved Radha pining in separation from him, and sung by Lata Mangeshkar, naturally) draws him irresistibly to Aunty’s place, where he becomes a regular, eventually setting Pushpa up in her own spacious suite.

The filmmaker is at pains to keep Anand’s ecstatic appreciation of Pushpa’s talents properly pure (he first praises her for “turning this room into a temple” and tells her that her name should be not Pushpa but Mira—after the Krishna-devoted Rajasthani saint-poet), but audiences need only recall the sultry love scene between these two in ARADHANA’s Roop tera mastana song sequence to read between the carefully-drawn lines. A similar inference is drawn by the upright Mahesh, a village neighbor who chances on Pushpa’s setup while searching for a flat in the city and is visibly disgusted, even while giving her the painful news that her mother (to whom she has regularly been sending money via the unscrupulous Nepal Babu) is actually long deceased—and that she too is “dead” as far as the villagers are concerned. Pushpa (who until then seemed quite happy with her silks, gold jewelry, cosmetics, and lavishly-decorated household shrine complete with images of Ramakrishna and the Mother) is freshly crushed, but is comforted, after a fashion, by Anand’s supremely melancholic ode to the cruelty and futility of life (and of grief about it), Chingare koi barhke (“If some ember bursts into flame [the rains will extinguish it]”), sung on a swaying boat being rowed along the night-lit Hooghly. It includes the beautiful and telling verse,

Don’t ask me how

The mansion of my dreams crumbled.

This saga wasn’t the work of outsiders,

But of those close to me.

If an enemy deals a blow,

Then a friend helps one recover.

But when a dear friend inflicts the wound,

Then who can heal it?

Much of the rest of the film (and there is plenty more) alternates between scenes of similarly restorative interventions by the tipsy but perspicacious Anand, and of Pushpa’s growing love for (and suffering over) the little boy Nandu, son of Mahesh, who now lives in the neighborhood. Nandu’s shrewish stepmother prefers her own three children, and the abused and half-starved lad gladly accepts the hospitality and treats proffered by the elaborately-coiffed neighbor lady whose house always echoes with singing—although this leads to still further abuse of both him and his benefactor by his conventionally moralistic parents.

Pushpa suffers in silence, eventually nursing little Nandu through a near-fatal illness and paying for his medical care—his recovery to full health and (cloying) cuteness is celebrated by the song Bada natkhat hai (“You are very naughty”), which evokes the love of foster-mother Yashoda for the young Krishna. Anand Babu, ever clad in the immaculate and crisply-starched kurta and dhoti of the Bengali bhadralok gentleman, reflects bemusedly on the futility and thanklessness of it all (e.g. in the song Yeh kya hua, “What happened?”). After wringing every possible tear out of this scenario of a star-crossed yet loving “family” (with Pushpa and Anand as surrogate parents to Nandu), the screenplay abruptly separates them, then fast-forwards to an epilogue in which the now-grown Nandu—a successful engineer—encounters the now-graying (but sober and even more sagely) Anand, who helps him to locate Pushpa (now reduced to scrubbing pots in a seedy boarding house full of garrulous Bengali types).

Needless to say, immortal love is (amid torrents of tears) resoundingly reaffirmed. Yet when all is said and wept, the film, despite its bathos, stands out not only for its lovely songs and its indictment of middle-class hypocrisy, but for its sympathetic and humane (if sanitized) treatment of prostitution—including such culturally-correct and telling vignettes as the artisan who must procure a lump of clay from a courtesan’s courtyard in order to mould the image of Durga for the Mother Goddess’ great autumn festival.

The Sky Entertainment DVD of AMAR PREM features a generally good quality print of the film, with subtitles thoughtfully provided for songs as well as dialogue. These are reasonably evocative, though the translator’s identification of the flowering shrub that little Nandu plants in Pushpa’s courtyard—in the very hole from which the clay for Durga’s image has been extracted—as “the blooming dale” obscures a key cultural point: it is, in fact, raat ki rani, the “Queen of the Night,” whose intoxicating fragrance spreads far and wide.