ANAND

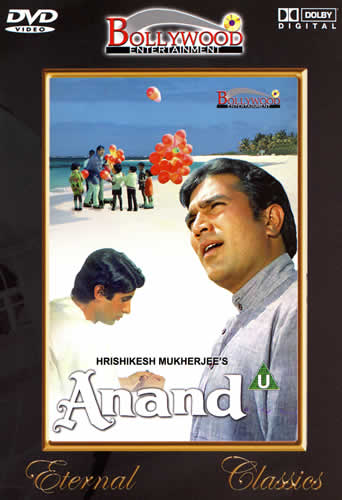

(“Joy.” 1970, Hindi, about 122 minutes)

Directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Produced by N. C. Sippy and Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Story: Hrishikesh Mukherjee; Screenplay: Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Gulzar, D. N. Mukherjee, and Bimal Dutta; Dialogue: Guzlar; Lyrics: Gulzar and Yogesh; Music: Salil Chowdhury; Cinematography: Jaywant Pathare; Art direction: Ajit Banerjee

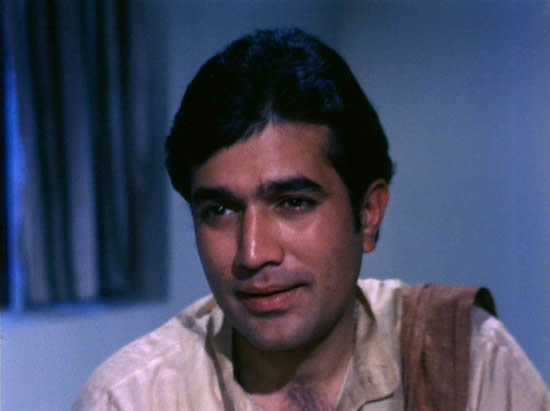

This multi-handkerchief film about a dying cancer patient whose infectious joie de vivre transforms the lives of those around him was one of the most successful of Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s “middle class” films (see notes on ANARI, 1959), and helped Rajesh Khanna establish the character of the fast-talking-but-lovable interloper that he was to deploy (more endearingly, in my view) in BAWARCHI (1972). Fondly regarded in India as a heartwarming tear-jerker, it buttresses a human interest story (on the order of the old Reader’s Digest “My Most Unforgettable Character” series) with the pathos of a losing battle with cancer, a fascination with new medical technology (Anand receives radiation treatments), often witty dialog, and a parade of cameos by veteran cinema luminairies Durga Khote, Johnny Walker, and Dara Singh. The film is dedicated to “the city of Bombay” (which however is not seen much except in the credit sequence) and to Raj Kapoor—a more plausible connection, since the title character’s brand of manic bonhomie suggests the overbearing screen persona for which Kapoor was famous. Anand, at least, has the excuse that he’s terminally ill and trying to drink life to the dregs, and he occasionally reflects on his own behavior—as when he remarks to his physician early in the film, “Whether you live seventy years or six months, life needs to be big, it doesn’t need to be long.”

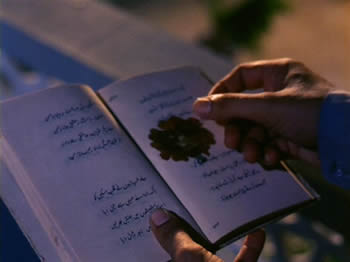

The film opens at a literary awards ceremony at which a brooding young cancer specialist, Bhaskar Banerjee, M. D., receives a prize for a “novel” entitled Anand. The doctor’s revelation that the book is, in fact, a true story extracted from his diary leads into the flashback comprising the rest of the film. Bhaskar recalls being initially discouraged in his medical practice because of the omnipresence of poverty in India—a reminiscence that occasions a “cameo appearance” by a real-live Bombay slum, evidently intended to assure viewers that Bhaskar’s compassion and public-service credentials are in order. This grimly familiar place and its denizens quickly disappear, however, behind the façade of bourgeois comfort in which Bhaskar and his friends reside (including car, servant, cushy bungalow, and Japanese tapedeck), and the arrival of the large-hearted and likewise middle-class Anand Sehgal appears to obviate the need to give any further thought to The Poor. Indeed, they are (as Jesus said) always with us, whereas Bhaskar will only have Anand around for a bit more than three months (distilled into two cinematic hours). Anand is preceded by a letter from a Delhi physician describing his terminal illness—a rare form of stomach cancer. Realizing that he has no treatment to offer, Bhaskar is initially repelled and even angered by Anand’s bouncy entrance—and here the film briefly but effectively explores the psychology of the physician, when Anand thoughtfully responds to an outburst by Bhaskar (who is appalled that he isn’t taking his illness “seriously”): “Ah, I understand, you aren’t angry at me, you’re angry at yourself, because you can’t help me.”

Though fully aware of the grim prognosis, Anand is determined to snatch whatever joy he can in the time left to him...and he particularly enjoys putting other people’s lives in order. After a brief stay in a private hospital, where he charms the nursing staff, he invites himself to live with Bhaskar and proceeds to take over the doctor’s waking hours. Far from resenting this, Bhaskar loves it! So does nearly everyone else whom Anand meets, comprising a cavalcade of star-powered stereotypes: the outwardly stern but inwardly maternal Goan headnurse Mrs. D’Sa (Lalita Pawar; cf. her similar and identically-named role in Mukherjee’s early film ANARI), the teary-eyed widow (Durga Khote), the brawny Punjabi wrestler (Dara Singh), and the madcap Muslim actor Isa Bhai (Johnny Walker).

It isn’t long before everyone is pleading with God—under His/Her several names and forms—for a last-minute miracle, but as Bhaskar finally concedes, “God needs good people as much as we do….” And so, with none-too-subtle symbolism (a tape running out, a bunch of balloons floating skyward), our hero makes his exit.

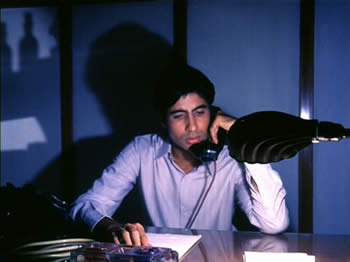

Viewed retrospectively, the film seems almost to be an allegory of the cinematic demise of Rajesh Khanna Superstar and his replacement by the (soon to be Angry) Young Man, Amitabh Bachchan, as his sensitive and soulful doctor-cum-diarist. Bachchan’s subdued character—with lanky physique, deep voice, and big, melancholy eyes—is meant to serve as counterpoint to the pudgier Khanna’s manic ebullience, and does, but it also hints at the “darker” heroic personality that was soon to emerge, and that would rule the Hindi screen for more than a decade. Tellingly, when the film was successfully re-released a few years after its first run, Bachchan’s image dominated the poster, ironically relegating leading man Khanna to “supporting” status.

How you feel about the film may largely depend on how you relate to its main character. Whereas some (like Bhaskar, his friends, and a large number of Indian viewers) may find him instantly endearing and heroically self-sacrificing, others may consider his intrusive and overbearing dosti more problematic and even annoying. After all, this is a guy who not only engineers his best friend’s crucial first “date” with the woman he wants to marry, but then insists on coming along, making it impossible for the lovers to communicate—which doesn’t matter, though, because Anand does all the talking for both of them! There is a cultural point here, concerning a manic, almost pathologically gregarious brand of Hindustani dost—of the sort witheringly satirized by Hindi author Mohan Rakesh in his portrait of a leech-like “Punjabi Bhai” acquaintance in the travelogue Aakhiri chattaan tak (“To Land’s End”) — who expresses his irrepressible “heart” qualities by hurling himself at innocent bystanders and by never permitting a “friend” to experience a moment of solitude or silence. This expansive yet oddly self-centered type, whose principal characteristics are rhetorical wit, frenetic energy, and a deep reservoir of on-tap emotion, may or may not actually exist in large numbers in India, but he is certainly a hardy trope of the Hindi cinema — successively reincarnated by (among others) Raj and Shammi Kapoor, Dev Anand, and more recently by Salman and Shah Rukh Khan. And in cinema-land, at least, he is invariably successful in his frenzied pursuits, whether wooing reluctant women, eliciting unfailing loyalty from men, or (here) dying gracefully and pathetically amid a clutch of sobbing friends whose lives he has forever altered for the better.

The film’s hit songs include two ballads: Kahin dur (“Somewhere far away…when the day fades”), sung by Mukesh, in which Anand reveals something of his own inner sorrow over a lost love, and the rollicking Zindagi kaisi hai paheli (“Oh what a riddle life is!”), sung by Manna De, and picturised on the Arabian Sea-shore under a glorious blue sky.

[The Bollywood Entertainment DVD of ANAND offers a generally excellent print of the film with good sound quality. The English subtitle track is serviceable, but subtitles are particularly helpless with a chatterbox like Anand, hence much of his verbal wit is lost. Songs too are regrettably left unsubtitled.]