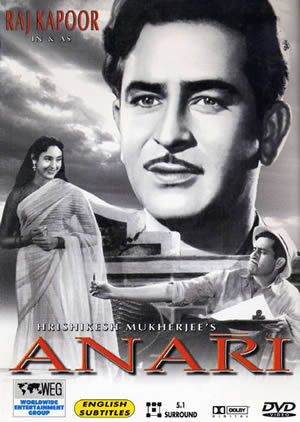

ANARI

(“the simpleton”)

1959, Hindi, approx. 157 minutes

Directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Produced by L. B. Lachman

Story, Screenplay, and Dialogues: Inder Raj Anand; Lyrics: Hasrat, Shailendra; Music: Shankar-Jaikishan; Cinematography: Jaywant R. Pathare; Art Direction: M. R. Achrekar; Settings: K. Damodar

In a directorial career spanning some forty years, Hrishikesh Mukherjee made an equal number of what are often called “middle class” films. The label refers to their assumed target viewers who, like most of the principal characters in their narratives, were urban, educated people of secure but not lavish means, employed in white collar or professional jobs. But the designation might equally refer to their stylistic location somewhere between big budget, operatic masala melodramas, and the more austere and personal (and usually commercially unviable) visions of so-called “artfilm” or “alternative cinema” directors. Though usually made on modest budgets, Mukherjee’s films adhere to many of the conventions of the mainstream commercial cinema—storylines that rely heavily on both comedy and pathos, music and dance scored by eminent Bombay composers, and big name (or “A-list”) stars—who regularly chose to work for Mukherjee both because of his benign personality and reputation for integrity, and because his scripts gave them the opportunity to appear in more challenging or non-standard roles (e.g., Amitabh Bachchan as a struggling musician in ALAAP, Rajesh Khanna as a dying cancer patient in ANAND, Dharmendra as himself in GUDDI). In contrast to the wide-canvas, “epic” look of more lavishly-budgeted films, Mukherjee’s have a characteristically closer-focus and unpretentious style that often displays crisp and inventive camerawork, as well as a resourceful use of modest sets and locations. Many of these films enjoyed appropriately modest commercial success when they were released, and they have held their own over the years and indeed, have grown more beloved to viewers with the passage of time. Today, Mukherjee (a Bengali who trained under the famed Bimal Roy, and who turned eighty in 2002) is regarded as one of the grand old men of the Hindi film industry.

ANARI was Mukherjee’s second effort as a director (after 1957’s MUSAFIR), and his first notable commercial success. Featuring Raj Kapoor and Nutan—both then at the height of their careers—and a very catchy Shankar-Jaikishan score, it is essentially another “Raju” film (showcasing Kapoor’s trademark character of lovable and idealistic, though naïve, middle class everyman, trying to navigate a callous and materialistic world), though both the character—here named “Rajkumar”—and the storyline are trimmed-down in suitably Mukherjee-esque style. Kapoor is more pensive and less frenetic than in the “Raju” films he directed himself (such as AWARA, SHRI 420, or JIS DESH MEN GANGA BEHTI HAI), and the narrative places him neither in a palatial mansion nor among rustics and slum-dwellers, but in the lower-middle-class digs of a Bombay Christian matron with the common Goan name of D’Sa (pronounced “Disa”—and possibly a Portuguese version of the Gujarati “Desai,” suggestive of the Hindu roots of some Goan Catholics). She is the proverbial sharp-tongued landlady with a heart of gold, though here too Mukherjee tweaks the stereotype and summons a superb performance from veteran character actress Lalita Pawar.

Mrs. D’sa daily berates her boarder—an unemployed artist who regularly loses jobs because of his innocence and scrupulous honesty—and threatens him (in endearingly substandard “Bombay Hindi”) with eviction, all the while dotingly preparing his meals, secretly slipping coins into his empty pockets, and praying to Lord Jesus for his success—for in fact she has inwardly adopted him as a surrogate for her deceased son, David. Pawar’s performance manages to lift this poignant scenario above cliché, and the characters’ reflections on the inter-communal mother-son relationship adds a nice note of social commentary—the irrelevance of ethnic and religious divisions in matters of the heart—that is (again in characteristically Mukherjee-esque fashion) sincere yet understated.

The film is more outspoken about class barriers, for poor-boy Raj soon encounters and falls in love with the proverbial Rich Girl, Arti (the radiant Nutan), an orphan who lives in an ostentatious mansion with her pharmaceutical magnate uncle Ramnath (Motilal) and a companion Asha (Shubha Khote) who doubles as girlfriend and maidservant. Attracted to Raj, Arti trades names and personas with Asha, pretending to be a poor working girl in the employ of an imperious heiress. This permits Raj to express his feelings for her, but their budding romance is threatened when Raj accidentally meets Arti’s uncle, impresses him with his honesty, and lands a job in his firm.

Further complications arise from a subplot concerning a flu epidemic: Ramnath and his corporate cronies—including an unscrupulous Hindu Vaishnava of ostentatious piety—discover that one batch of their patent flu medicine actually contains poison, but in their greed to reap handsome profits they suppress this information. Raj’s world begins to fall apart when he discovers “Asha’s” true identity as the rich Arti, and Arti’s uncle—who rose from poverty himself and now fears and despises the poor—threatens her with dire consequences unless she breaks with Raj. To make matters worse, Mrs. D’sa goes searching for her distraught “son” in a downpour and then comes down with the flu; the doctor, of course, prescribes the tainted medicine. When the poor get sicker, the rich get meaner, and Motiilal’s subtle performance in the film’s final reels effectively suggests the thin line that separates corporate-executive respectability from rapacious criminality. Though things get pretty grave, the director salvages a happy ending—yet, again, not the ecstatic apotheosis one would expect from a more mainstream melodrama; but an understated resolution that is somewhat incomplete, bittersweet, and oddly satisfying.

ANARI’s six musical numbers—several of which became notable hits—are uniformly strong and work effectively to move the plot forward. Ban ke pancchi (“forest bird”) introduces Arti’s carefree character as she and a group of girlfriends cycle through the scenic Western Ghats (cf. the similar “establishing song” of the heroine in PADOSAN, which appears to quote this scene). Rajkumar’s own establishing song, Kisi ki muskurahaton pe (“someone’s smiles”), which celebrates his altruism and empathy, is a catchy Shankar Jaikishan classic with a jaunty Rive-Gauche accordion accompaniment. Raj and Arti’s blossoming romance unfolds through two lovesongs set in gardens, Woh chand khila woh tare hanse(“that waxing moon, those smiling stars”) and Dil ki nazar se (“with the eyes of the heart”). 1956 is a cabaret number featuring the inevitable Helen and a riot of low-budget sartorial and choreographic hybridity (Cossack and Flamenco meets fifties moderne!). Raj’s discovery, at Arti’s lavish birthday party, of her true identity, occasions the song Sab kuch seekha humne (“I’ve learned everything [except how to be deceptive]”), in which idealistic lyrics disguise a message of bitterness and betrayal. Arti’s pain at having to break with Raj occasions the anguished Tera jaana (“your leaving”).

[The Worldwide Entertainment Group (WEG) DVD of ANARI features an exceptionally good print of the film—truly a delight to watch!—and also offers superior English subtitles (although the key word anari—connoting an inexperienced, unsophisticated, or naïve person—is regularly rendered “idiot”). As is all too common, though, the DVD fails to provide subtitles for songs.]