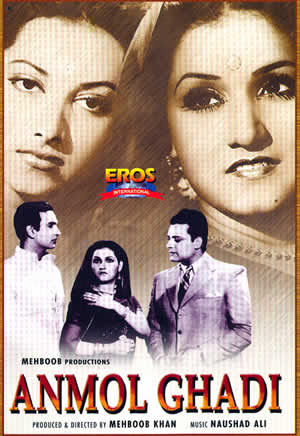

ANMOL GHADI

(“the priceless watch”)

Hindi, 1946

Directed by Mehboob Khan

Story: Anwar Batalvi; Screenplay and dialogues: Agha Jani Kashmiri; Lyrics: Tanveer Naqvi; Music: Naushad; Dances: Krishna Kumar

Albeit sometimes awkwardly plotted and woodenly acted, this languorous and mannered meditation on intractable class difference and frustrated love is memorable for the always-interesting camerawork of Faredoon A. Irani and a full bouquet of twelve songs by the great Naushad. A further point of interest is that this is one of relatively few pre-Independence films currently available on DVD; moreover its principals, including the popular star Nurjehan, who would emigrate to Lahore soon after Partition, do their own singing—for this was an era in which playback dubbing by non-actors, though already utilized, was not yet dominant. Students of Mehboob’s oeuvre will recognize motifs that anticipate the more complex and unsettling ANDAZ (1949), and there are also echoes of the unavoidable (in this period) Devdas story (memorably filmed by P. C. Barua in 1935), especially in the ineffectual and melancholic hero who is loved—to no avail—by two beautiful women: a chaste and unattainable childhood sweetheart and a coquettish but rejected adult admirer.

|

The film opens with a jaunty roadsong (Udhan khatolepe, “I go by flying carpet…and you cannot catch me”) celebrating the love but dramatizing the social distance between two children: the rich girl Lata and poor boy Chander, in the idyllic rural setting of Jehanabad (“flourishing world”). While Lata wears a stylish frock and rides in a horse carriage with two liveried attendants, the kurta-and-dhoti clad Chander trots behind like a faithful puppy, albeit rolling a toy wheel in sport. At the portico of Lata’s mansion, her doting district-officer father bribes her with his pocket watch before chasing off Chander, who is hiding in the bushes. In the next scene, Chander’s widowed mother (Leela Mishra), who ekes out a living grinding wheat, explains to the pouting boy that true friendship is not possible between rich and poor. But when Lata’s father is transferred to Bombay and packs up his household, the girl presents Chander with her father’s watch as a memento of their love, and asks him to come to Bombay one day to find her. Astute viewers who guess that (a) he will eventually do so, (b) the outcome will not be happy, and (c) the watch—emblematic of both modernity and fate—will loom large in the mise-en-scene, have correctly divined the gist of what ensues, minus a few (sometimes confusing) plot details. But they will want to stay on for the songs, beginning with Tera khilona toota (“Your toy is broken”), sung by a whimsical toy vendor to a crowd of village children as a commentary on Chander’s abandonment by the Bombay-bound Lata (he falls while chasing her carriage, breaking the wooden bird that he planned to give her as a keepsake in return for the watch). Its part-nonsensical lyrics combine fatalistic sant-style motifs about the illusory world with droll evocations of Indian modernity, anticipating the mood of much of the film.

|

|

|

|

Predictably, Chander’s melancholia proves permanent, and despite the tireless labor of his mother to educate him for a successful career, he grows (via a time-lapse marked by her turning millstone overlaid with a succession of schoolbooks) into a dreamy musician and sitar-repairer (Surendra Nath) who shows little inclination for work, preferring to sit under a tree sighing over poems and the fateful pocketwatch (occasioning the song Woh yaad aa rahi hai, “That memory returns…of a vanished world; this pitiable tale and tearful song, to whom shall I tell them?”) while his now-wizened mother continues her interminable grinding—a fate that he likewise laments but does nothing to allay. To the rescue comes, inexplicably, one Prakash (Zahur Raja), a rich friend from Bombay, who magnanimously moves Chander and his mother to the big city and sets the former up in a musical instrument shop. Chander repays his benefactor by being moody, unreliable, and occasionally insulting, but the indefatigable Prakash, who has money to burn, is motivated by the purest dosti. Moveover, he and Chander share a passion for the poetry of an author known as “Renu” (“grain of sand”), actually the secret nom de plume of a soulful young society woman who is, in fact, the grown-up Lata (Nurjehan), and who dedicates her best-selling oeuvre to her evergreen memories of the lost paradise of her childhood in Jehanabad.

Lata’s best friend is the vivacious Basanti (Suraiya), another rich girl who develops an unrequited crush on the young manager of a sitar store (Chander, of course), even as its absent owner, Prakash, becomes engaged to the morose but dutiful daughter of a powerful government officer—in short, Lata. These four ill-starred friends and lovers proceed to wander in and out of each other’s orbits, generating heartache and misunderstanding, but more importantly songs like Aawaz de kahaan hai, (“Tell me where you are,” sung by Lata as she pines for Chander in her moodily lit art-deco boudoir), Mai dil mein (“I embraced pain in my heart, when our eyes met,” in which Basanti—charmingly mirrored in the polished lid of the grand piano she plays—reveals her new infatuation to Lata, who of course does not realize that its object is her own lost childhood love), and Ab kaun hai mera (“Now who is left for me?,” sung by Chander after the death of his long-suffering mother and the revelation that Prakash is to marry Lata).

Even with fairly stereotypical lyrics, these (and other) songs are so musically effective and inventively picturized that it is difficult to choose a favorite—though another contender must certainly be Man letha hai angdai (“My heart twists and turns…youthful ardor suffuses my life”), Basanti’s sensual ode to Chander’s purloined pocketwatch, which she fondles and swings while writhing on an ornate bed beneath a portrait of herself.

|

|

Recapitulating Barua’s Devdas (and a long line of literary precursors, whose archetype is perhaps the mad Sufi lover Majnun) and anticipating Guru Dutt’s Vijay in PYAASA, Chander ends up distraught and disheveled, and (after putting in a morose appearance at his best friend’s marriage to his own beloved), abandons the world to wander off into the wilderness. He is pursued by the equally-reduced Basanti, whose love he cannot return, and who now appears sadhvi-like in a white sari. The final word on this lose-lose situation (for the newlyweds back in Bombay are presumably equally miserable) is conveyed by a reprise of the toyseller’s jocular song about a heartless heavenly Player and his two-bit human puppets. This is a grim conclusion indeed, but, thank Heaven, we can just walk away from it—humming the delightful tunes of Naushad. |

|

[The Eros International DVD of ANMOL GHADI is of tolerable image quality. Subtitles are generally good, although (as is unfortunately the usual case with Eros DVDs) none are provided for the songs—an especiallygreat defect in presenting this memorably musical film to an international audience!]