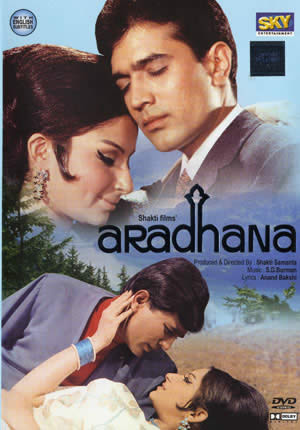

ARADHANA

(“adoration, worship”)

1969, Hindi, 180 minutes

Produced and Directed by Shakti Samanta

Story and screenplay: Sachin Bhowmick; Dialogue: Ramesh Pant; Lyrics: Anand Bakshi; Music: S. D. Burman; Art Direction: Shanti Das; Cinematography: Aloke Das Gupta

When thinking of the dynamics of gender relations in India, I sometimes recall Garrison Keillor’s description of his fictional hometown of Lake Woebegone, Minnesota: “…Where the women are strong and the men are good-looking.” This could serve as a kind of summary-sutra for ARADHANA, a weepy drama of female self-sacrifice, buoyed by a famous Bakshi-and-Burman score, that casts Sharmila Tagore as the ill-starred heroine Vandana (a name that, like the film’s title, connotes “praise” or “worship”) and Rajesh Khanna in the double role of her lover and then son. Its dramatic success as a “golden jubilee” film (one that played for more than fifty weeks in major urban centers) made Khanna a superstar and led to a string of hits in which he starred (many directed by Samanta or by Hrishikesh Mukherjee) between 1969 and 1973—when the actor’s career went into abrupt decline due to the advent of the Next and Bigger Thing, Amitabh Bachchan.

As the credits roll, we see a radiant, white-clad Vandana being denounced in a courtroom, and (after tearfully refusing to speak in her own defense) being sentenced to life imprisonment for murder. One need not have taken Hindi Cinema 101 to grasp that she is doubtless Innocent, but the film will defer explaining her “crime” for its first half, which unrolls as a flashback from her lonely prison cell. As it opens, Vandana is returning from college to her hill-station home, where she lives with her father, Gopal Tripathi, a medical doctor and widower. As she rides the narrow-gauge train through the mountains, she hears a young airman, Arun Varma (Khanna) on the adjacent motor road singing the amorous song Mere sapnon ki rani (“Oh Queen of my dreams, [when will you come to me?]”) while he eyes her flirtatiously. Their paths soon cross in her hometown, where Arun begins to woo her more ardently; and although she is the very model of maidenly modesty and deferral, her jovial and progressive father proves to have no objection to a “love match.”

Soon, with the further blessing of Arun’s avuncular boss Air Commodore Ganguly (Ashok Kumar), the engagement is sealed (and celebrated with the sun-drenched love songs Kora kagaz tha, “My heart was like a blank page,” and Gunguna rahe hai, “The bees are buzzing,” both performed against a backdrop of forests and snow-covered peaks). But before the planned nuptials can occur, Arun and Vandana pay a visit to a Shiva temple where, at the prompting of a cheerful priest, they impulsively exchange garlands and “marry before God.” A sudden storm then forces the lovers into a nearby bungalow where they doff their wet clothes—she substituting an artfully wrapped blanket for her soaked sari, and he building a fire. The blanket is red, and the firepit resembles a Vedic altar; eyeing each other hungrily, they circle the blaze while (substituting for a mantra-chanting priest) an amorous young man in an adjacent room sings the sultry Roop tera mastana (“Your beauty intoxicates me”).

The film’s most erotic song picturization thus simultaneously manages to encode the key elements of a perfectly dharmic Hindu marriage ritual, although it necessarily remains a scandalous secret, unsanctioned by family and “society.” The obvious ensues (off-camera, of course) and though the virtuous Vandana worries about it the next morning, Arun assures her that they will be formally wed in just a few days, when he returns from a flying trip to Delhi.

But alas, Fate is cruel, and the young airman’s plane crashes. He survives only long enough to remind the weeping Vandana, at his bedside, of his dream of having a son named Suraj (“sun”) who, like him, will become a pilot and range the skies; he extracts from her the promise to make this dream come true. Soon after his death, the distraught Vandana indeed discovers that she is pregnant, and reveals to her shocked father—who could arrange a face-saving abortion—that she intends to keep and raise the child, dedicating her life to the “worship” (aradhana) of her lost love. Despite her father’s blessing, Vandana’s plight now grows grimmer. Arun’s family (eager to inherit his property) mocks her tale of a secret “marriage” and denounces her as a loose woman, and soon after this her father expires. When she gives birth to a beautiful son, a lady doctor advises leaving him at an orphanage door and then coming the next day to “adopt” him—the only means by which she can salvage respectability as a single mother. But this plan too goes awry, as the baby is accidentally given to a prosperous couple, the Saxenas, whose own child was stillborn. When Vandana contacts the husband and attempts to retrieve the boy, admitting the real facts behind his birth, Mr. Saxena convinces her to join the household as a nursemaid, so that her son can grow up with the advantage of the family’s wealth. Thus begins Vandana’s long, worshipful “penance” for her romantic indiscretion, as she nurtures the child, indeed named Suraj, maintaining the illusion that he is someone else’s son, while nevertheless forming a close bond with him, celebrated in the lullaby-like song Chanda hai tu (“You are my moon [and sun]”).

Worse trials lie ahead. When the greasy, foreign-returned brother of Mrs. Saxena, Shyam (Madan Puri) tries to rape Vandana, eight-year-old Suraj comes to her defense. She now gladly accepts a jail sentence for murder rather than endanger her child. When she is released on good behavior after twelve years, she learns that Mr. Saxena has died and his wife and son have moved to an unknown place. Homeless once more, she accepts the invitation of the kindly jailer (himself a widower and about to retire) to come to his house in Delhi as his adopted sister and assist in the raising of his spirited teenage daughter Renu (Farida Jalal). It is not long before Vandana learns that, like her “aunt” before her, Renu too has a weakness for daring young men in flying machines, and in fact is in love with a twenty-year-old pilot named….. Ah well, watch the movie—keeping a hankie or two handy—and everything will (in time) be revealed.

The songs of Aradhana were very popular and several remain well known today. Although most are romantic duets performed by Lata Mangeshkar and Kishore Kumar or Asha Bhosle and Mohamed Rafi, the film's most haunting tune is perhaps the bhajan-like Kahey ko roye (“Why do you weep?”), unusually and soulfully sung by composer Burman himself as a voiceover commentary on Vandana’s many trials.

Despite its suffocating patriarchal morality—which condemns a young woman to a lifetime of solitary adoration of a dead fiancé and self-effacing nurture of the son who is essentially his clone—this is a female-centered film, graced with a memorable performance by Sharmila Tagore. Her character’s two decades of tribulations recall those of two classical heroines celebrated in the Mahabharata, Shakuntala and Draupadi. Like the former, the innocent Vandana, associated with nature and the hills, is ardently pursued and eventually seduced by a more sophisticated urban lover, who then leaves her; their informal marriage is unrecognized by society and she is scorned and humiliated because she bears his child, yet she devotes herself to the boy’s upbringing so that he may one day inherit his patrimony (here, the “kingdom” of the now conquered and militarized sky). And like Draupadi in the epic’s Book of Virata, Vandana, in order to achieve her object, disguises her identity and takes employment as a maidservant in a wealthy household, wherein (in the absence of a male protector) she is sexually harassed by her mistress’ brother, who finally pays for this crime with his life; the blame for his death then falls on her. Yet the outspoken assertiveness of the two epic heroines contrasts sharply with the passive and stoic endurance expected of the modern and respectably middle-class heroine, whose resistance to injustice is here largely expressed through self-imposed suffering.

[The Sky Entertainment DVD of ARADHANA features a good quality print of the film. Optional English subtitles are, happily, provided for all song lyrics as well as for dialogues.]