(“bands, horns, and revelry,” Hindi 2010)

Story and directed by Maneesh Sharma

Produced by Aditya Chopra for Yash Raj Films; Screenplay & dialogs: Habib Faisal; Music & background score: Salim-Sulaiman; Lyrics: Amitabh Bhattacharya; Choreography: Vaibhavi Merchant; Director of Photography: Aseem Mishra

This low-budget romantic-comedy with little-known actors scored surprising and (in this viewer’s opinion) well-deserved success, and several of its catchy songs achieved notable popularity. What’s refreshing about it is less its fairly predictable plot—about two recent college grads who form a partnership in the wedding-planning business on the understanding that they will not get romantically involved with each other (take a wild guess what happens…)—than its exuberant mise-en-scène set on location at various rungs of middle-class Delhi (with appropriately au-courant Hindi, Punjabi, and Hinglish slang in the dialogs and song lyrics), its satirical but affectionate portrayal of the Indian appetite for huge and ostentatious weddings, the pleasing chemistry between its young stars, and its surprisingly graphic and casual approach to pre-marital sex, which, as of December, 2010, seems not to have upset Indian filmgoers. The film is also notable for its affectionate portrayal of the brash energy of India’s capital city—with vignettes of the Delhi University campus, the Delhi Metro, the ice-cream carts near India Gate, and crowded neighborhoods like Janakpuri.

About the film’s title: Hindu weddings in modern times typically involve a procession (called a “baaraat”) of the groom’s party, accompanying the groom (who is usually mounted on a horse), to the home of the bride’s family (or some venue hired by them) where the actual marriage ceremony and subsequent wedding feast will take place. This procession should be as colorful and loud as resources permit (substitution of an elephant or brand-new Mercedes for the horse is not uncommon at upper-income levels), and may be accompanied by dancing, fireworks, lamp bearers, hired performers (sometimes hijras or male transvestites), as well as smartly-attired male kin (generally sporting new outfits gifted to them by the bride’s folk). An absolutely essential feature is a uniformed marching band with plenty of brass instruments (“baaja”). This convention has a long history dating back to the colonial-era fascination with the noise, spectacle, and coordination of British-run military bands (for the full story of this endearing artform from an ethnomusicologist’s perspective, see Gregory P. Booth’s Brass Baja, Stories from the World of Indian Wedding Bands, Oxford U. Press, 2005). None of these taken-for-granted customs (elements of which have been endlessly recapitulated in any Hindi film involving a wedding—which is to say, most—as well as in a few hits that centrally feature one, such as HUM AAPKE HAIN KOUN!) receives much screen time here, so their invocation in the title, besides being pleasingly alliterative, merely informs us that the full package of what constitutes an “Indian wedding” will figure in the storyline.

And so it does. 20-year-old Shruti Kakkar (Anushka Sharma) is a Delhi University student who dreams of becoming a planner of themed and packaged weddings for her middle-class neighbors. When fast-talking schoolmate Bittoo Sharma (Ranveer Singh) tries to put the make on her, she rebuffs him coldly, as put off by his potential distraction from her plans as by his cocky attitude and small-town background (including substandard Indian English: he pronounces “business” as “bij-niss”). But like most besotted Hindi film heroes, Bittoo does not give up easily. After crashing a sangeet (a pre-wedding musical party involving, here, teasing songs and competitive dancing between the two family “teams”—accompanied by the spunky song performed by Shruti, “Baari Barsi”) at which Shruti is working as a wedding-planner’s trainee, Bittoo creates a video of her dancing—but she is not impressed. His would-be wooing soon takes a backseat, however, to his desperation to find a job that will save him from his father’s intended plans for him, post-college—cutting sugarcane on the family farm near Saharanpur, U.P.—and he begs Shruti to take him on as a “bij-niss” partner or even a “peon” (go-for). A series of lucky breaks reveal that Bittoo is not without talents and a certain charm, and so Shruti agrees, though insisting on the no-romance clause noted earlier.

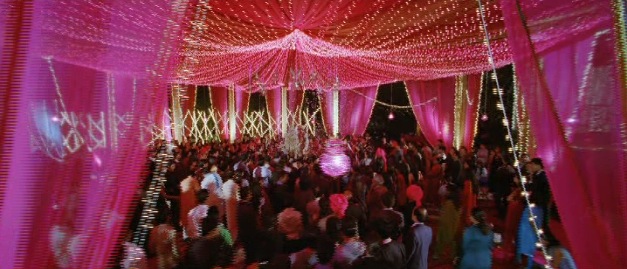

Their company, called Shaadi Mubaarak (“wedding congratulations!,” in its colloquial, everyday Hindi-Urdu idiom) begins small, showing a lower-middle class family in Shruti’s own neighborhood of Janakpuri just what can be achieved with Rs. 250,000 and a lot of youthful energy and verve. Bittoo’s last-minute drafting of his dorm friends’ grunge band, and his own performance with them of “Ainvaye” (“just like that/for no reason”, the film’s standout hit single) gets everyone happily dancing and does much to insure the success of the new company. Soon, wealthier couples and their families are flocking to Shaadi Mubaarak for “that desi feeling”—which is to say, good-old-fashioned Indian excess and plenty of “bling,” offered up in an all-inclusive contemporary package that boasts computer-simulation of décor, revolving stages, and mike-connected staffers to insure perfect choreography of all elements, from bijli(electric lighting) to kababs. The young partners are helped along by a large-hearted Muslim flower seller, Maqsood, and his friend, a small-time but plucky Sikh caterer from Trilokpuri, Rajinder. The weddings get bigger and so do the perks—like a car to replace Bittoo’s motorbike.

The somewhat vulgar and sometimes overbearing Bittoo proves to have definite charms, both for female clients and for Shruti—for example, he can make a dynamite cup of chai, an essential skill that she lacks—and these, combined with a few glasses of champagne and some slow-dancing after a particularly successful gig that launches Shaadi Mubaarak into the higher echelon of the business, leads to an unplanned but steamy coupling—a salacious breach of contract—that shakes up both young people. Their awkward handling of the morning-after leads to the break-up of both their relationship and business, and in turn, to the film’s somewhat less-satisfying labor, in its second half, to repair both. But if a happy ending is happily unavoidable (with the girl, stereotypically, coming to her senses and giving up her pride when confronted with the sheer heart-quality of her lover), at least it gets delivered during a humongous wedding extravaganza set in a Rajasthani fort, and yields to a light-hearted credit sequence that recaptures some of the film’s earlier earnest energy and unpretentious charm.

[The Yash Raj DVD of this film offers good image quality and good subtitles for both dialog and song sequences.]