BARSAAT KI RAAT

(“one rainy night”)

Hindi, 1960, approx. 142 minutes.

Directed by P. L. Santoshi

Produced by: R. Chandra

Story: Rafi Ajmeri; Dialogue: Sarshar Sailani

Screenplay: Bharat Bhushan, P. L. Santoshi; Cinematography: M. Rajaram; Editing: P. S. Khochikar

Art Direction: Gonesh Basak; Playback: Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhonsle, Sudha Malhotra, Mohamed Rafi, Manna Dey, S. D. Batish, Shankar Shamboo, Balbir, Suman Kalyanpur, Kamla Barot

Lyrics: Sahir Ludhianvi; Music: Roshan

Despite the poor image quality and subtitles on the available DVD (see below)—there are at least three good reasons to watch (and vah!) this under-appreciated gem of a film:

- it belongs to the comparatively rare category of “Muslim social” (cf. CHAUDVIN KA CHAND), which offers a contemporary and essentially secular tale centered around main characters who happen to South Asian Muslims, fairly realistically depicts their cultural and social life, and features chaste and elegant Urdu/Hindi with a rich Persian resonance.

- it offers three notably strong female characters, superbly played by talented actresses, including the incomparable Madhubala, then at the height of her career (cf. MUGHAL-E-AZAM).

- it has a memorable score, with lyrics by the great Sahir Ludhianvi (an Urdu poet doubtless most in his element when—as here—composing for a film about Urdu poets), sung by a stellar list of playback singers, and culminating in a series of dazzling qawwaliperformances (of love-saturated and Sufi-inflected couplets on the pleasures and pains of love) that are among the best ever filmed.

After a credit sequence accompanied by a charming light-classical song of the rainy season (Garajta barasta saavana aayo re, “Oh friend, the thundering rains have come [but my beloved has not returned]”), the story opens with the struggling poet Aman Hyderabadi (Bharat Bhushan, i.e., “Bhooshan” in the credits) temporarily lodging with Mubarak Ali of Gulbarga, a qawwali maestro and his two performing daughters. The younger, Shabab (“youth”) is a mischievous flirt, but the elder, Shama (her name means “candle” and refers to the standard moth-and-flame trope in Urdu love poetry) is deeply in love with the young boarder. Their father’s musical career has suffered a setback because of a defeat in a qawwali “duel” with the party of the legendary Daulat Khan, and Mubarak Ali beseeches Aman’s poetic help in winning a rematch. But his own straightened circumstances compel the young man to first return to his home city of Hyderabad to seek his fortune composing ghazals for the local All India Radio station.

While roaming the countryside looking for inspiration for his first commission, Aman takes shelter from a nocturnal monsoon downpour on the verandah of a blacksmith’s cottage, and is soon joined there by a radiant young woman who has been drenched by the storm; a lightning flash causes her to involuntarily clutch his chest, their eyes meet, and then….he lights a cigarette and she departs. She is soon identified (to us) as Shabnam (Madhubala), the spirited elder daughter of the city’s Police Commissioner (K. N. Singh), and an ardent lover of poetry—especially the ghazals of Aman Hyderabadi, whose divan or book of odes she keeps at her bedside. Naturally, she is excited when the radio announces that he will himself now perform a new one, and so begins the film’s remarkable title song (listed on the menu by its opening phrase, as is standard practice; Zindagi bhar nahin), in which the poet soulfully recounts his chance meeting with a beautiful girl during a thunderstorm.

In all my life I’ll never forget that rainy night,

For I encountered a lovely girl that rainy night…

As the verses unfold, their artful rendition of the details of the meeting makes the delighted Shabnam gradually realize that the man she recently met was indeed her beloved poet.

Students of cultural studies should likewise be delighted with this sequence (and others to follow), in which the (then-still-proliferating) technology of radio serves as romantic go-between and love-medium: as Aman sighs into his studio microphone, Shabnam responsively swoons over her stylish console.

Events soon bring the two together again when Aman surreptitiously sings to Shabnam during a poetic function, (Maine shaayad tumhen, “Perhaps I have seen you somewhere before”), and then is hired to tutor Shabnam’s precocious kid sister. But their budding love cannot be concealed, and it arouses the ire of Shabnam’s stern policeman father, who despises poets and moreover has plans to marry his daughter to one Aftab, the son of a judge-crony in Lucknow. When he banishes Aman from the house, Shabnam escapes to join her lover, and their flight is assisted by the blacksmith at whose home they first met. But before they can arrange a marriage ceremony (and needless to say, they chastely sleep apart while this is pending), Shabnam is recaptured by her father’s minions and brought back to Hyderabad.

The unfolding plot now alternates between Aman’s quest to recover his beloved, and his old friend Mubarak Ali’s similar efforts to regain his lost reputation as the greatest of qawwals. Along the way there are splendid songs like Mayus to hun (“Despondent am I [at your faithlessness]”), sung by Aman to the clang of the blacksmith’s hammer. The two narratives come together when Aman—who has followed Shabnam’s family to Lucknow—listlessly agrees to help a pretentious, third-rate poet compose fresh songs for the Hyderabadi singer Chand Khan, whose qawwali party will face Mubarak Ali’s in a competition.

This leads to the first of the three infectiously energetic qawwali numbers, Nigahen naaz ke (“[What will happen to those struck by] our proud glances?”), in which the heavily-adorned sisters Shama and Shabab boast (with good reason!) of their coquettish beauty—yet lose to Aman’s superior lyrics; and in the process the perky Shabab loses her heart to the handsome young singer Chand Khan (the feeling is mutual). A rematch is arranged, and this time Aman rallies to the aid of his old friend, and the song Pahechanta hoon khoob (“I know very well [your intentions]”) leads Chand Khan to defeat (and to a not-undesired marriage to his young conqueror Shabab).

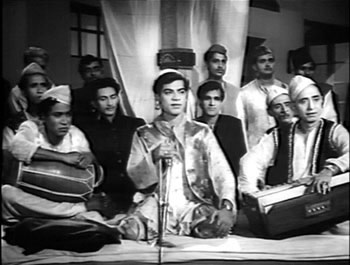

Mubarak Ali still needs to best the famed Daulat Khan, and for this purpose his party, accompanied by Aman, proceeds to the famed Sufi shrine of Ajmer Sharif, the tomb of the great saint Muinnuddin Chishti and the mecca of all qawwals, especially at the time of the annualurs or death-anniversary of the saint. Coincidentally, the Hyderabad P. C.’s family goes on pilgrimage there too, to seek the saint’s healing blessings for the soon-to-be-married Shabnam, who is pining away (as we know, from love sickness for Aman). Her suffering is soon matched by that of Mubarak Ali’s elder daughter Shama when she discovers that her beloved Aman has given his heart to another. The life-lines of all these young sufferers come together in a brilliant knot during the final qawwali-duel at the shrine, Na to carvan ki talash (“I seek neither a caravan [nor a traveling companion]”), a musical, emotional, and cinematographic tour-de-force that builds to a crescendo proclaiming the supreme power of ishq or passionate, self-effacing love.

As Chand Khan accompanies his new wife Shabab on harmonium, she and her sister match the maestro Daulat Khan verse-for-verse with pointed lessons on the trials of lovers. But when her own inner pain prevents Shama from continuing, Aman takes over, spinning fresh couplets that up the ante into the higher realms of mysticism and religious syncretism, with allusions to Hindu mythology (including, among other things, Krishna and the gopis—alas, these become virtually unrecognizable in the crude subtitles).

Given that the whole contest is being simulcast on All India Radio-Ajmer, and that Shabnam and her family are, naturally, listening in their lodgings, it is no surprise that the ecstatic climax of the qawwali—a sequence that should have all good-hearted viewers practically jumping out of their seats—will also triumphantly resolve the tangled strands of the plot. And if a rain-drenched happy ending were not sufficient grounds for rejoicing, there’s the fact of having witnessed a film that neither tokenizes nor “others” Muslims, that affirms Indian religio-cultural diversity without recourse to preachy platitudes, and that showcases self-possessed women who manage to get their way.

The Samrat Collections DVD of this lovely film is, regrettably, below average on several key counts: in original print used, digital transfer of it, and English subtitles. (One tell-tale indicator of how careless these folks are is the fact that neither of the star images on the DVD box actually appears in this film: that of Bharat Bhushan wearing a forehead-tilak is apparently taken from BAIJU BAWRA—wherein he plays a Hindu musician—and the similarly bindi-sporting Madhubala with umbrella in hand is nowhere seen in a film in which she plays a Muslim girl who twice gets drenched in downpours!) Although subtitles are provided for songs as well as dialogue (something I ceaselessly urge on DVD manufacturers), it is a bit of a mixed blessing here, since the translation is often poor and the English substandard or even confusing. Still, the non-Hindi-knower can manage, and the film remains eminently worth savoring for all the reasons indicated above.