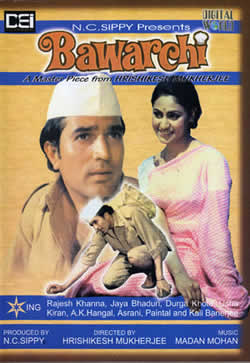

BAWARCHI

(“the cook”)

1972, Hindi, approx. 2 hours

Directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee

Produced by N. C. Sippy

Story: Tapan Sinha; Screenplay: Hrishikesh Mukherjee; Dialogues: Gulzar; Songs: Kaifi Azmi; Music: Madan Mohan; Cinematography: Jaywant Pathare; Art: Ajit Banerjee

To the often-heard middle-class Indian lament that “You can’t get good servants anymore!,” this comedy—by India’s master of the so-called “middle class” film (see notes on ALAAP)—has the answer: a talented cook and all-around handyman who appears out of the blue, gladly takes on extra and even demeaning tasks, manifests unfailing good cheer, and actually requests a salary lower than he is offered, because of “inflation” (afflicting his employers, that is!). Incidentally, he is also a soulful poet, gifted musician, enchanting storyteller, master psychologist, and—in a word—Mahatma, who takes charge of dysfunctional families and turns the petty animosities and irritations of everyday life in extended households into a succession of opportunities for the manifestation of selfless love and service. More surprisingly still, he transforms (with the help of Hrishkesh Mukherjee and his talented team) this potentially saccharine scenario into a highly original, witty, and entertaining film that truly deserves the adjective “heartwarming.”

An opening shot of a velvet curtain appears ready to serve as a backdrop for the film’s credits (as was the case in Mukherjee’s early hit ANARI), but instead, the voice of Amitabh Bachchan offers an unusual oral credit sequence, followed by a prologue introducing all the characters, of the sort spoken by the sutradhara or “director” in classical Sanskrit drama. Retired postmaster and widower Shivnath Sharma shares his comfortable but unostentatious home (ironically named “Shanti Niwas” or “Abode of Peace”) with three quarrelsome sons and their families. Ramnath (A. K. Hangal) is a deferential head clerk who nightly drowns his sorrows in cheap country liquor; his nagging wife Sita Devi (Durga Khote) suffers from gout and a martyr complex. Their daughter Meeta is an aspiring but self-centered kathak dancer. A second son Kashinath is a schoolteacher and self-important intellectual, whose wife, Shobha Devi, doesn’t get along with her sister-in-law. The youngest son Vishvanath, a.k.a. “Babloo” (Asrani) is a would-be film “music director” (i.e., composer), presently working as assistant to the composer team “Rajnikant-Nyarelal”; he affects the self-absorbed persona of the Artist—which naturally precludes helping out around the family home. The burden of housekeeping amidst the din of constant petty squabbles among all these denizens of the “Abode of Peace” falls heaviest on Krishnaa (Jaya Bhaduri), the orphaned daughter of another Sharma son who died with his wife in a car accident—especially when servants quit abruptly because they cannot bear the stormy domestic atmosphere.

This happens regularly, until one day when an amiable young man named Raghu (Rajesh Khanna) turns up, announcing that he is their new bawarchi or cook—though, as soon becomes clear, making excellent cuisine is only one of his many talents. A smooth talker who claims to have worked for a whole galaxy of eminent personalities, acquiring knowledge and skills from each, Raghu is initially distrusted by the Sharma sons, who fear that he might be a conman (one is rumored to be working the area), but they are soon won over by his effusive attentions to their needs, his magical skills in the kitchen, and his overall take-charge attitude—represented by his habit of exuberantly concluding pronouncements with a mock trumpet-fanfare: “Taa-ta-raah!” (a Khanna-ism that quickly entered popular speech).

With peace, happiness, and timely meals restored to the household, it is only a matter of time until the hapless Ramnath gets a promotion at work, the feuding wives become as close as sisters, and shy daughter Krishnaa wins a dance competition (beating out the arrogant Meeta by performing a piece taught her, of course, by cook Raghu). Then, just when the household seems to be living up to its name, Tragedy Strikes: the sleeping family is robbed of a wooden chest, which the eccentric patriarch had insisted on keeping under his bed, that contains their major assets in the form of old wedding jewelry. Worse still, the chief suspect is none other than the saintly—but now apparently absconded—bawarchi.

The “surprise” ending that Mukherjee abruptly tacks onto this dramatic climax may not surprise attentive viewers; moreover, it leaves a number of plot details unexplained. No matter: the great charm of this film lies in its saucy and rapid-fire dialogue, its unpretentious mise-en-scene, and its parade of memorably-acted characters who evoke all-too-familiar types in the middle-class milieu of smaller Indian cities. Like the inhabitants of R. K. Narayan’s beloved “Malgudi” stories and novels, the denizens of Mukherjee’s world live constrained lives and have dreams to scale, yet they are viewed through a lens that manages to be at once satirical and affectionate. Shanti Niwas feels familiar and homey—from the faded bazaar “framing pictures” on its walls, to the slippery drain area in the courtyard that nobody wants to clean—and so do its inhabitants, who interact incessantly in its privacy-proof living space. Even the outspoken interventions of the bawarchi suggest the casual intrusiveness that servants often assume in Indian households, and Rajesh Khanna’s diction, gestures, and body language effectively evoke a simultaneously deferential and spirited subaltern.

As in some of his other films (e.g., GUDDI) Mukherjee pokes fun at Bombay cinematic conventions even while largely adhering to them—perhaps permitting his middle class viewers to feel intellectually superior to the “masses” who (supposedly) unreflectively accept such fare. When Babloo is stumped over a song he is composing for a DEVDAS-like sequence in which a hero sees his beloved being driven off in a bullock cart to marry another man (adding the “new twist” of having the cart driver rather than the spurned lover sing it), Raghu comes to the rescue with the lovely song Tum bin jivan (“What sort of life is it without you?”); simultaneously, the dreamy and impressionable Krishnaa “picturizes” the song in her mind, with herself as bride-to-be and her boyfriend Arun as the suffering lover—Raghu, wearing a rakish pink turban, is of course the singing cartman.

Later, during the morning raga sung by Raghu, Bhor aayee gaya andhiyara (“Dawn has come and darkness fled”)—a light classical tour-de-force which gets the entire family singing—would-be music director Babloo (who, we have been told, has “stolen countless foreign melodies,” though he has never yet crafted a hit) breaks into a guitar riff that parodies the Western-pop-influenced style of the then-prominent R. D. Burman.

[The DEI DVD of BAWARCHI offers an excellent quality print of the film (though on the copy I viewed there were some momentary digitalization flaws in the image toward the end of the film), with good subtitles for dialogue. Unfortunately, none are provided for the film’s three songs. The film is also offered on DVD by “Bollywood Entertainment,” and the disc appears to be of comparable quality; however it offers subtitles for the first of the three songs, Tum bin jivan (though not, oddly, for the other two).]