Chaudhvin ka Chand

(Moon of the 14th Day, i.e. Full Moon)

(1960) Hindi, 169 minutes

Produced by Guru Dutt for Guru Dutt Films. Directed by Mohammed Sadiq. Screenplay by Saghir Ushmani, from his story “Jhalak” (“A Glimpse”). Dialog by Tabish Sultanpuri. Music by Ravi Lyrics by Shakeel Badayuni. Cinematography by Nariman Irani.

Starring: Waheeda Rehman, Guru Dutt, Rehman, Minoo Mumtaz, Johnny Walker.

[Notes by Corey K. Creekmur]

The exquisitely produced Muslim social Chaudhvin ka Chand seems relatively neglected within the pantheon of Guru Dutt’s late films. Perhaps because it appeared between the now-undisputed masterpieces Kaagaz ke Phool (1959) and Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam (1962), the former the last film Guru Dutt is officially credited with directing, and the latter the final film he produced,Chaudhvin ka Chand shines less brightly in its setting, surrounded by striking gems. Nevertheless, the film was (following the box-office disaster of Kaagaz ke Phool) Guru Dutt’s biggest box-office hit, and his first to play in an international film festival (Moscow, 1962, which Guru Dutt attended). But even Guru Dutt’s greatest champion, Nasreen Munni Kabir, describesChaudhvin ka Chand as “most conventional in story and in treatment” in her seminal Guru Dutt: A Life in Cinema (Oxford, 1996). However, the film is in many ways a remarkable work that deserves critical rediscovery and reevaluation.

There remains some speculation surrounding the production circumstances of the film, though Kabir’s critical biography clears up most of the facts: though the critical and commercial failure of Kaagaz ke Phool may have prevented Guru Dutt from signing his name to another film, he seems to have chosen M. Sadiq to direct this film because he simply felt that a Muslim subject demanded a Muslim director, though Dutt supervised the picturization of the film’s songs, employing color cinematography for the first time. (Dutt’s offer to Sadiq was also a generous way to help the commercially unsuccessful director improve his career and finances.) The project also perhaps derived from Guru Dutt’s desire to make a film based upon a qawwali story, as the director adored the Sufi musical form. In any case, while behind the scenes a number of new names were assembled for this production, the film’s cast again gathered many of the performers who had become closely associated with Guru Dutt’s increasingly tragic vision of the world.

As the Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema notes, the film “pivots around the Islamic practice of purdah, which forbids women to show their face to men outside their immediate family.” In fact, the film richly expands and complicates this basis in a cultural practice by constructing an extended study in vision and veiling, treated in both comic and tragic variations that structure the film’s plot of misidentifications and misunderstandings as well as its rich stylistic pattern of blocked and obscured views. Recent film critics invested in the power and erotics of the gaze would do well to discover this veritable treatise on the subject of focused looks and momentary glimpses, which intersects the essential looking of cinema itself with the specific visual conventions of Muslim India.

The film initiates its focus immediately, when we meet a nawab, Pyare Miyan (Rehman) and his comic friend Shaida (Johnny Walker) on the streets of Lucknow. Though Shaida is chastised for peering at women, his more sophisticated friend is thunderstruck by his glimpse of the face of Jamila (Waheeda Rehman) when she lifts her veil. Our own view of the striking face of one of Indian cinema's most beautiful stars has the effect of immediately implicating us in the film’s moral tensions: we have paid for our right to gaze freely upon the faces of cinema’s stars, yet this undeniably erotic look – and others the camera will offer us – occurs within the dramatic and cultural context which forbids such invasive views. And while the film is obviously set in a world that supports male privilege, it often complicates matters by regularly shifting its point of view between men and women. In the first elaborate musical number, as the nawab peeks at the women gathered in his home for his sister’s wedding party, the women recognize his presence and watch their watcher. As he hides – blind beneath a sheet – in his room, Jamila and a friend comically dissect his painted portrait which “watches” over the room. Thus begins the film’s rich and varied play with screens, veils, curtains, performances, and disguises, together rendering all of the film a constant circulation between clear-eyed vision and (often preferable, or more alluring) distorted views.

The unfolding of the plot moves from the misidentifications of Shakesperian comedy to the misunderstandings of well-intentioned people that result in tragedy. The nawab’s ailing mother is anxious to see her son married, and has arranged his marriage; still seeking his briefly glimpsed Beatrice, he asks his poor friend Aslam (Guru Dutt) to marry the girl his mother has secured – who is of course Jamila. The film will then trace the series of errors and obligations that complicate this situation and results in the three friends understanding the prices they have paid attempting to insure one another’s happiness. The film’s long-delayed revelation, when the nawab finally realizes that the woman he desires is his best friend’s wife, is a brilliant sequence that shifts our attention between visual perspectives (as well as external and internal voices) that are intricately composed through reflections in mirrors. The scene summarizes the film’s catalog of visual structures as well as the moral consequences that they generate.

If the extended misunderstandings seem implausible (despite their grounding in a social system that isolates men and women from casual contact), the emotions that link the characters to one another and motivate their attempts to perform extreme sacrifices feel plausible and real. Although Jamila is central to the plot, the film concentrates on the obligations of male friendship (dosti), one of the great topics of popular Indian cinema but rarely given the depth and sincerity of this example: as in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam this film’s ostensible “happy ending” for a couple is outweighed by the painful cost of such joy. (One continually senses that the three friends at the center of the film are playing out their off-screen, longtime affection as well: Johnny Walker’s comic role is especially tempered by moments of convincing affection for his suffering friends.) Friendship forces these fellows to take action by acting: attempting to play the part of the wayward husband that will allow the wife he adores to divorce him and marry his best friend, Aslam’s joyless visits to a brothel make him resemble Devdas, the great Indian romantic anti-hero (Guru Dutt fans will recall that the ill-fated film being made in the ill-fated Kaagaz ke Phool is a remake of Devdas, a story of self-destruction that Guru Dutt’s own life seemed to sadly replay.) Shaida, on the other hand, approaches his roles – and costume changes – with great relish, disguising himself as a elderly holy man to photograph women in the bazaar, and finally donning the uniform and self-important mannerisms of a police inspector.

As in all Guru Dutt films, the song sequences are notable highlights, featuring the voices of perhaps Hindi cinema’s three greatest playback singers, Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, and Mohammad Rafi, the latter shifting effortlessly between Guru Dutt’s heartfelt and Johnny Walker’s comic songs. Two numbers are given special treatment by being filmed in color (see note below), and Guru Dutt’s tendency to advance his story through songs, with the rhythm of music and editing in collaboration, is as strong as ever. For example, the first major number, Sharma Ke Ye Kyon … (“Why do these women adjust their veils?”) cuts between the nawab and women peering at one another while the lyrics comment upon this action (and the tradition of purdah), all within a tightly organized interchange of sound and image. If this film doesn’t finally achieve the overall impact of an earlier masterpiece like Pyaasa, the technical skills that made Guru Dutt one of the masters of Hindi cinema’s golden age, and unsurpassed in the art of song picturization, are still on display in this penultimate work.

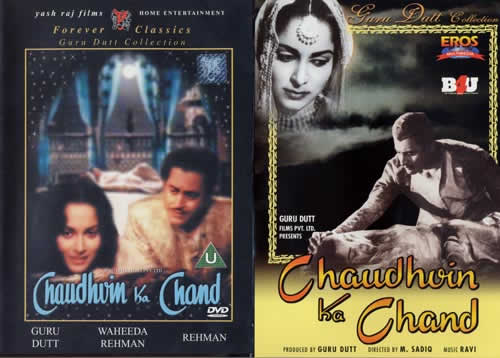

[Chaudhvin ka Chand is available on DVD from both Yash Raj Films and Eros/B4U. The image quality of both versions is generally very good, through both include some rough spots and choppy transitions. The subtitles on both copies are fairly straightforward but necessarily fail to capture the rich texture of the original Hindi-Urdu dialog, though the Eros copy may be somewhat more accurate (it at least correctly identifies the final swallowed object as a diamond, not the “poison” that the Yash Raj copy provides.) However, the Eros DVD does not subtitle the film’s songs, and its subtitles tend to slip off of the bottom of the screen. A more significant difference between the copies is that the Yash Raj DVD includes only the title song in color, whereas the Eros DVD includes both the title song and the brothel number “Kabhi Raazi Mohabbat” in color . (The Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema claims that these two color sequences appear in “later release prints … although designed for b&w,” a rather confusing claim since the sequences were clearly filmed in color.) The Yash Raj DVD, like all of the company’s Guru Dutt Collection titles, also includes Nasreen Munni Kabir’s illuminating documentary “In Search of Guru Dutt.” Guru Dutt fans may be fated to owning both versions, since each provides something the other lacks.]