Chhalia

(“the cheat”)

Hindi, 1960, BW, ca. 135 min.

Directed by Manmohan Desai

Produced by Subhash Desai/Subhash Pictures

Cinematography: Bipin Pandya, A. N. Subramaniam; Music: Kalyanji-Anandaji

What might appear at first glance to be a routine Raj Kapoor twilight-period vehicle — in which the aging star, en route to the self-pitying excesses of Sangam and Mera Naam Joker, offers yet another predictable “Raju” avatar — is in fact a remarkable film in several respects, and one that deserves to be available in a better quality print than the one I have viewed (details below). For one thing, it is the first film credited to the talented Manmohan Desai as director, an assignment that came about through Desai’s producer brother, who wrangled a break for Manmohan working with a star he adored. Though Kapoor and his team seem to have been largely behind the project, the resulting narrative of a separated and then reunited family, with a strong theme of communal harmony within an overarchingly Hindu India, indeed prefigures the epic “lost-and-found” tales for which Desai would later be celebrated (cf. AMAR AKBAR ANTHONY, NASEEB, MARD). Moreover, this is one of only a handful of films prior to the late 1990s that deal, even obliquely, with the subject of Partition — here, with the fate of women abducted or separated from their families during the migrations and massacres that accompanied that terrible event. In the late 1940s, both the Indian and Pakistani governments launched “Recovery Operations” and passed “Restoration” laws, aimed at reuniting such women with their families — only to find that, in many cases (as in this film), the families wanted nothing further to do with their “dishonored” sisters, wives, daughters and daughters-in-law (cf., for a more recent exploration of this theme, PINJAR). The fact that the abandoned and long-suffering woman in Chhalia is played by the radiant Nutan, and that her story is punctuated by a very creditable musical score by Kalyanji-Anandji (with assistance from Laxmikant-Pyarelal), further distinguishes this film, as does the moody, atmospheric cinematography (for which the credits—which seem unusually brief—list only “assistant” cameramen Pandya and Subramaniam, as noted above).

|

It opens with a speeding train — Indian cinema’s trope of modernity, but also its reminder of links to lost homelands, and of other trains bearing the refugees and victims of 1947. Indeed, we quickly learn that this is a Lahore-Delhi train, and that it carries Hindu and Sikh women being repatriated to India five years after Partition. One of these is the heroine, Shanti (“Peace”), and as she tells her sad story to fellow refugee women, we go via flashback to a time “before people began making foreigners of their neighbors” and to a verdant and luxurious Lahore of sprawling parks and rustic lanes, in which Shanti and her girlfriends dance and wave their billowing dupattas to the carefree and romantic song Baaje payal(“anklets ring… [I don’t know for whom my young heart waits]”).

Returning to her parents’ mansion, Shanti discovers that her engagement is indeed being arranged, to the same handsome but haughty young motorist — one Kewal (Rehman), the son of a wealthy attorney — she had saucily accosted on the road. Their embarrassed second meeting abruptly transitions to the scene of their wedding, then to a blissful nuptial night which is interrupted by arson and rioting, as the hysteria of Partition begins and Hindu families must flee Lahore.

This is the first of several cuts that are so rough that (although the Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema warns that “Desai seems impatient with the finer points of plot structure…”) one suspects that the print used to make the digital version has been damaged and repeatedly (and badly) spliced over the years. More (and worse) confusing transitions will follow, though it is still possible to make out the basic story.

A second flashback sequence shows Shanti, stumbling alone through the lanes of riot-torn Lahore, saved from a mob by a powerful Pathan (Afghan warrior) named Abdul Rehman Khan (Pran). Though Shanti is terrified of what this “rescuer” may do to her, Khan greets her as a sister and announces that his own sister, Sakeena, has been left behind in India. He will shelter Shanti while never even looking at her face, in the hope that his sister may receive similar treatment “from some Hindu or Sikh.” Viewers thus learn that Shanti, even in five years in Pakistan, has not been dishonored, and so is ultimately eligible, within the film’s conventional patriarchal ideology, for reunion with her husband, though this will be repeatedly deferred and challenged. |

|

|

|

These plot twists lend considerable emotional weight to the film, for the plight of many “Shantis” was well publicized in 1950s India. Spurned by her natal family in a heart-wrenching scene in which they visit the refugee camp in which she is staying, but refuse to recognize her — a paternally-imposed “deceit” that will deprive Shanti’s anguished mother of the power of speech — she is briefly comforted by Kewal, who has left his own disapproving family in order to be with her. But his acceptance of her turns to disgust when he learns that she has a five-year-old son with the Islamic name “Anwar.” And though Shanti insists that Kewal is his father, the little boy gives his dad’s name as “Abdul Rehman,” and Kewal flees in a rage.

These bitter disappointments lead Shanti to resolve to end her life, but the suicide note she composes accidentally falls into the hands of Chhalia (Raj Kapoor) and he intercepts and saves her. A lovable con-man, Chhalia is Kapoor’s Chaplinesque “Raju” in all but name (to underscore this point, he strolls several times past posters for his own earlier films!), with ill-fitting trousers and jacket, comical walk, a penchant for small children and dogs, and an establishing song in the grand AWARA and SHRI 420 tradition. Its refrain goes,

The entry of this odd but familiar hybrid character (who is at once both “poor” and “middle class,” brimful of love, and a “criminal” who is apparently not much of a success at crime) into a semi-realist narrative about repatriated Partition abductees may seem an odd turn, but it feeds a subplot set in a satisfyingly surreal Old Delhi, where Chhalia resides in a hovel set atop a crumbling city wall.

Chhalia welcomes Shanti — who has now lost her son to an orphan boys’ school, where the teacher is in fact his own father, Kewal — into this “home” (after first removing the Western pin-ups from its walls) and she begins a new life as his chaste housekeeper. Knowing little of her past, he slowly falls in love with her (celebrated in the joyous rainy season song Dam dam diga diga[“Everything is soaked”] in which Kapoor dances Gene Kelly-like, but with a purloined umbrella, amidst a torrential downpour).

Enter fate in the form of Abdul Rehman Khan, who has journeyed to India in search of his lost sister and also to settle some old (unexplained) score with Chhalia, which he plans to do by abducting the lovely young woman in Chhalia’s company (recall that Khan has never laid eyes on Shanti during the five years she stayed with him). Pran gives a strong performance as the Pathan heavy, including an impressive fight scene with Chhalia, but he is finally bested and then further devastated by the knowledge that the woman he planned to dishonor is his own adopted “sister.” When he is told that he must return to Pakistan, as his visitor’s permit is about to expire, his dazed and pathetic queries: Pakistan? Pakistan kahaan hai? Hindustan kahaan hai?(“Pakistan? Where is Pakistan? Where is Hindustan/India?”) offer one of the film’s most touching moments, suggesting the bewilderment, at the lunacy of man-made boundaries, of the insane hero of Saadat Hasan Manto’s famous short story “Toba Tek Singh.” Yet there is a “lost-and-found” surprise waiting for him, too, aboard the Lahore-bound train. |

|

It remains for Chhalia to renounce his own love for Shanti and bring about her reunion with her husband and son. Though this denouement may have been taken for granted, the film effects it through a bang-up finale set during the climax of the Delhi Ramlila — the annual re-enactment of the story of Rama and Sita — when a huge effigy of Ravana, Rama’s demonic adversary and the abductor of Rama’s wife, is set afire at an outdoor fair.

Here the film invokes another Rama story, known to all Indians and already implicit in Chhalia: that of Rama’s later rejection of his pregnant wife because of suspicion that she may have been unfaithful to him during her captivity, and that the child she carries may not be his. Whereas in the Ramayana it is the poet-sage Valmiki who finally attests to Sita’s purity before Rama, here it is Chhaliya-Kapoor as India’s conscience, and naturally he does it through a song, heavy with mythological allusions, about the plight of abducted women (Gali gali Seeta, “In every lane, Sita")

Even on an obvious soundstage set, the delivery of this song’s rousing lyrics, accompanied by dramatic quick cuts of the confluence of milling crowds, the principal characters, and the towering effigy, makes for a most satisfying climax. |

|

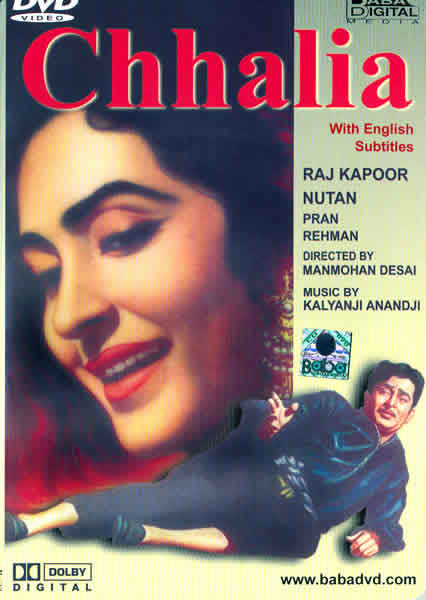

[Chhalia is available on DVD from the Indian distributor Shemaroo and the international firm Baba Digital. Although some of Shemaroo ’s discs have image quality superior to those of the same films marketed by international copyright-holders (e.g., Shemaroo’s Shree 420looks better than the Yashraj Films version), their Chhalia unfortunately comes with all the continuity problems noted above, and one can only hope that this does not mean that the sole available print of this film has the same faults. To the company’s credit, though, image quality is quite good for what survives, and although the subtitles contain some of the irritating abbreviations favored by text-messagers (e.g., “UR” for “your”), they are fairly accurate, and (wonder of wonders!) are provided for songs as well. The Baba Digital DVD has equally good overall image quality, but even worse continuity problems, with sections of songs missing. However, its subtitles are better than those of the Shemaroo version. Take your pick! Given its gutsy theme, Chhalia is an important film to watch, warts and all.]