DEEWAR

(“The Wall,” 1975, Hindi, 160 minutes)

Directed by Yash Chopra

Produced by Gulshan Rai

Story, screenplay, dialogue: Salim Khan, Javed Akhtar; Lyrics: Sahir; Music: Rahul Dev Burman; Art direction: Desh Mukherjee; Cinematography: Kay Gee

This well-crafted and memorable saga is today widely recognized as one of the key Bombay films of the 1970s. It recapitulates the basic frame story of MOTHER INDIA (1957), in which a mother recalls in a long flashback the chain of events that led her to destroy the favorite of her two sons because he had turned against the Law. Yet it also reorients this tale to make the sons and not the mother its central focus, and to arouse viewers’ sympathy, above all, for the wayward, rebel son—an approach that was also followed in GUNGA JAMUNA (1961), though that film’s rural setting is here traded for the great city of Bombay, to which the mother and sons, like countless other migrants, come in search of a better life. Like its distinguished predecessors in exploring the divided-sons theme, DEEWAR aptly illustrates how the commercial cinema can use image, character, and emotion to subvert and question its own surface messages. Released in the same year in which Indira Gandhi declared a state of national Emergency and suspended basic constitutional rights (in part because of the kind of labor unrest depicted in the first part of the flashback), it shared top box office honors with SHOLAY and JAI SANTOSHI MAA, and is now regarded as one of the crucial films in establishing Amitabh Bachchan’s archetypal persona as an angry young (usually proletarian) hero who would dominate Indian cinema for the next decade. With its stylish editing and minimal songs, the film holds up remarkably well today, and is a good choice for exposing the uninitiated to the Bachchan phenomenon, as well as to the rhetorical artistry (which can be sensed here even through less-than-ideal subtitles) of Salim-Javed, the inspired dialogue team who were crucial to the development of the Bachchan star text.

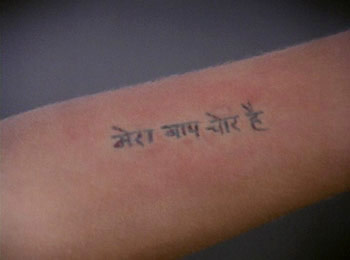

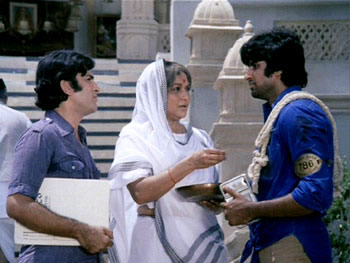

The film opens at a police awards ceremony, where sub-inspector Ravi Verma (Shashi Kapoor), who is being commended for heroic service, insists that his medal be given to his widowed mother Sumitra Devi (Nirupa Roy). As she reluctantly takes the stage at her son’s side, the visibly grieving woman hears the cheers of the crowd and is propelled into memories of another gathering some twenty years before, when her husband Anand Verma, a union leader in the coal mines, presents the demands of his striking fellow miners to their cynical capitalist boss. The latter retaliates by having his thugs kidnap Verma’s wife and two young sons (Masters Alankar and Raju), and threatens them with death unless the unionist signs a sellout contract relinquishing all demands and surrendering even the right to strike. A broken Verma capitulates, only to become the target of his comrades’ rage. Nearly beaten to death, he lies in a hospital bed listening to his wife, now freed by her captors, tells him that “people will soon forget” —even as crowds of children chant the slogan “In every lane there’s the cry: ‘Anand Babu is a swindler.’” Unable to bear the humiliation, the broken Verma slips out of the hospital one day to (evidently) spend the rest of his life riding trains, abandoning his wife and sons to a fate that quickly worsens. When Vijay, the elder, is seized by several drunkards and forced to submit to having his arm tattooed with the stinging message meraa baap chor hai (“my father is a thief”), Sumitra decides to flee the miners’ colony with her boys; a calendar picture of Bombay’s Marine Drive, behind her on the wall, morphs into their destination.

Finding shelter with other pavement dwellers under an overpass, the once lower-middle-class family struggles for survival in the heartless metropolis. When little Ravi reveals his dream of going to school—to the ironic strains of uniformed schoolchildren singing the patriotic anthem Sare jahan se achcha, Hindustan hamara (“The best in all the world, our India!”)—his elder brother takes a job as a shoeshine boy to help make it come true. For her part, mother Sumitra labors on a construction crew, faints, and is taunted by a lecherous overseer for her “delicacy”—provoking a violent reaction from the protective Vijay. Yet she remains the model of maternal Hindu piety, regularly taking the boys to a Shiva temple, which Vijay (who clearly has a bone to pick with God) refuses to enter. The smiling priest’s message to mother and younger brother—“Don’t force him! He will come when he’s ready”—occasions the visual sequence that flash-forwards us to a graying Sumitra, an educated and perky, though still unemployed Ravi, and a brooding blue-collared and unshaven Vijay (Amitabh Bachchan), now employed as a coolie on the Bombay docks.

Here Vijay learns from a Muslim comrade that his brass identification badge is lucky, since it bears the number “786” (the numerological equivalent of the Arabic letters that spell bismillah, “In the name of God”). This badge denoting hard labor and identification with Muslim subalterns (a recurring feature of the Bachchan persona) becomes the only talisman in the youth’s radically de-sacralized world, and indeed protects him when he challenges the authority of the thugs who regularly extort protection money from the dock workers for their smuggler boss Mr. Samant. Vijay makes the decision to fight back in a cafeteria under a poster of Mahatma Gandhi—a juxtaposition that neatly suggests the move away from Gandhian ideals of nonviolence to a more confrontational and aggressive style of mobilization. In a well-choreographed fight scene, Vijay beats a garage-full of Samant’s henchmen to pulp, a success that quickly endears him to Samant’s arch rival, the smuggler Davar, who becomes a surrogate father (and soon, business partner) to Vijay. After a neat sting operation against Samant, Vijay acquires undreamed of wealth, a lavish home (into which his bewildered mom and brother shift), and is even able to buy the high-rise on which Sumitra had once labored.

Ravi meanwhile suffers repeated disappointments in his own job search, though his spirits are buoyed (via the song Tujhe paya hai, “I’ve found you”) by his steady girlfriend Vina (Neetu Singh), herself the daughter of a successful police inspector (Manmohan Krishna). The latter eventually suggests his own line of employment to the young man, and Ravi is ecstatic when his appointment comes through. After a training camp (and another lovesong with Vina), Ravi hits the streets with the zeal of a cop-vert, undertaking the “heroic” shooting and capture of a fleeing thief who turns out to be a boy clutching a few loaves of bread, meant for his starving family. The scene in which a chagrined Ravi faces the boy’s parents—another set of decent people fallen on hard times—evokes both pathos and disquiet. Although the father (A. K. Hangal) stoically commends the officer for his deed, endorsing the “official” message that all criminals must be treated equally, the mother’s unforgiving rage conveys (to those who can look beyond the obvious stereotype of “emotional” femininity) the inequality inherent in Ravi’s role as agent of a law that is applied with disproportionate severity against the poor. But rather than cause Ravi to question the whole police enterprise (an undertaking that would in any case have been difficult in a Hindi film in 1975), the incident cements his resolve to take on a big case that he had at first refused: that of smuggler king Davar and his young partner, who Ravi now knows to be none other than Vijay Verma. The stage is thus set for fraternal conflict.

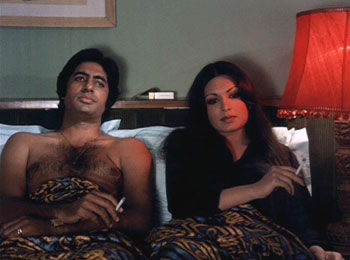

But first Vijay too must find romance, via Anita (Parveen Babi), a “fallen woman” who nevertheless still keeps in her wardrobe the spangled red sari her mother had once given her in the hope of a decent marriage. Though both brothers’ women are only peripheral to the story, Anita’s character is sufficiently developed to further enhance our sympathy for her and for Vijay, especially when she reveals to him that she is carrying his child. Vijay’s plan to marry and go straight is derailed by a brutal revenge attack by Samant, and by the determination of the relentless Ravi, which together lead inexorably to the tragic climax.

The dialogue in this film is nearly as celebrated as that of SHOLAY (also scripted by Salim-Javed); e.g., the scene in which, after Ravi reveals Vijay’s criminal connections to Sumitra and she and he flee the ill-gotten mansion for more modest digs, Vijay summons his brother to a last meeting under the overpass where they spent their childhood. Here he angrily challenges his brother by comparing their lifestyles:

Vijay: Your principals, your ideals! Of what use are your ideals? … These ideals, for the sake of which you’re ready to stake your life, what have they done for you? A job that pays 400-500 rupees, a rented flat, a government jeep, two sets of uniforms? Look, here I am and there you are. We both rose up from this sidewalk, but today where are you and where have I gotten to? Today I have buildings, property, a bank balance, a fine home, a car! What do you have?

Ravi: I’ve got Mom.

Or consider mother Sumitra’s famous speech, after she hands Ravi the pistol with which he will hunt down his brother, and then prepares to depart for the temple in which she has promised to meet her elder son:

Vina: You’re going, Mother?

Sumitra: Yes. The woman has discharged her duty. Now the mother goes to wait for her son.

Indeed, that the mother herself prefers Vijay to Ravi will have been obvious to viewers throughout the film, but just in case there’s any doubt, the script has her actually say this, not long before the climax, to her earnest-faced younger son, a disclosure that potentially puts a different and more troubling spin on Ravi’s furious pursuit of the fleeing smuggler. Though “justice” of a sort is finally done, the penultimate scene in the Shiva temple—before the flashback ends with Sumitra’s stricken face at the awards ceremony—leaves open the possibility that Ravi’s “heroic” fratricide is more a violent ritual sacrifice with clouded motives than the exercise of due process of Law.

[The DEI/Eros International DVD of DEEWAR offers a fine quality print of the film and good subtitles. The three songs, however, are unsubtitled.]