The DEVDAS Phenomenon

by Corey K. Creekmur

(Notes on 3 DEVDAS films and the novel that inspired them.)

DEVDAS (1935), Hindi version, 140 minutes.

Produced by New Theatres. Screenplay and Direction by P. C. Barua

Cinematography: Bimal Roy Music: Rai Chand Boral and Pankaj Mullick Dialog and lyrics: Kidar Sharma

Starring: K.L. Saigal, Jamuna, Rajkumari, and K. C. Dey

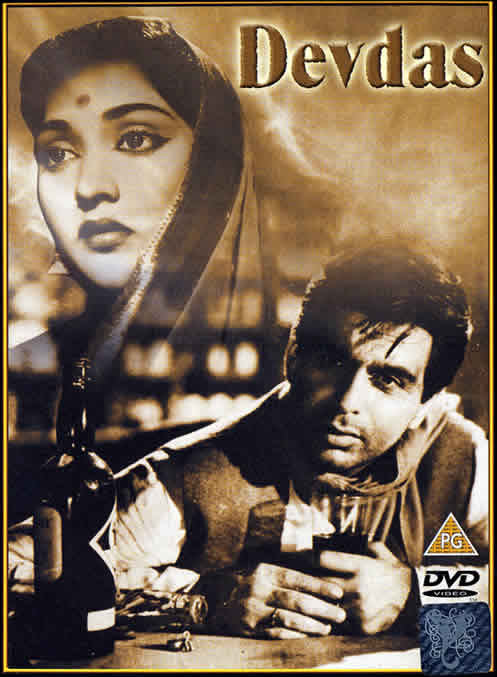

DEVDAS (1955), Hindi, 161 minutes.

Produced and Directed by Bimal Roy. Music: S. D. Burman Lyrics: Sahir Ludhianvi

Starring: Dilip Kumar, Vyjayantimala, Suchitra Sen, and Motilal

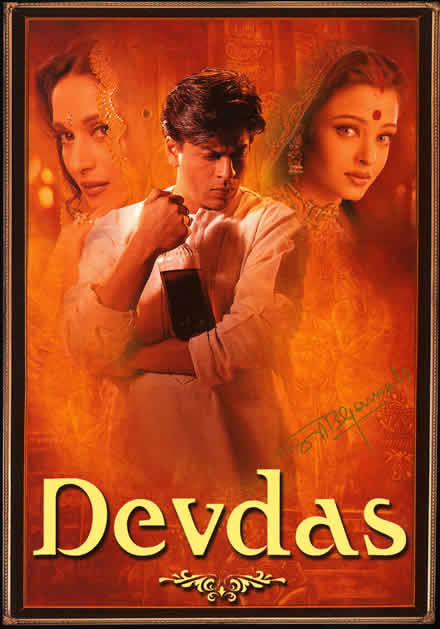

DEVDAS (2002), Hindi, 184 minutes.

Directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Music: Ismail Darbar Lyrics: Nusrat Badr

Starring: Shahrukh Khan, Madhuri Dixit, Aishwarya Rai, and Jackie Shroff

Dilip Kumar as Devdas (1955)

The tragic triangle linking the self-destructive Devdas, his forbidden childhood love Paro [Parvati] and the reformed prostitute Chandramukhi was first told in the popular and influential 1917 Bengali novella by Saratchandra Chattopadhyay (1876-1938) [sometimes rendered as Sarat Chandra Chatterjee or Chatterji, among other variants]. The story has since become one of the touchstones of popular Indian cinema. An adaptation starring Phani Burma (later a notable Bengali director) was filmed in 1928 by Naresh Chandra Mitra, but the first widely influential version was directed simultaneously in Hindi and Bengali in 1935 for New Theatres by P.C. (Pramathesh Chandra) Barua, son of the Raja of Gauripur. Barua cast himself as Devdas in the (recently rediscovered) Bengali version, and the legendary pre-playback singing star K. L. (Kundun Lal) Saigal (who has a cameo role singing two songs in the Bengali film) starred in the extremely popular Hindi version; because both Barua and Saigal suffered from their character’s alcoholism, the suggestion of a pathological identification with the role of Devdas has haunted later figures attracted to the story as well. Devdas also exists in at least one Tamil (P. V. Rao, 1936), Malayalam (Ownbelt Mani, 1989), and two Telegu verions (Vedantam Raghavaiah, 1953 and Vijayanirmala, 1974), as well as a Bengali remake (Dilip Roy, 1979), though its most prominent versions following Barua’s film featuring Saigal are undoubtedly the remakes in Hindi by Bimal Roy starring Dilip Kumar in 1955, and by Sanjay Leela Bhansali starring Shah Rukh Khan in 2002.

In addition to these many “official” versions of Devdas, the story and its tragic characters have also served as crucial referents for such major Hindi films as Guru Dutt’s PYAASA (1957) and especially his KAAGAZ KE PHOOL (1959), which involves a dissolute director remaking Devdas as a film within the film. (Guru Dutt is yet another key figure in Indian cinema whose biography unfortunately resonates with the tormented and self-destructive Devdas.) Indeed, as Gayatri Chatterjee suggests, Devdas is the archetype of what she tentatively calls “the genre of the self-destructive urban hero” in Indian cinema. A loose adaptation of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, PHIR SUBAH HOGI (Ramesh Saigal, 1958) features Raj Kapoor in a rare Devdas-like role, whereas MUQADDAR KA SIKANDER (Prakash Mehra, 1978), a more or less unofficial remake, forges the unexpected link between the early 20th-century upper-class Bengali aesthete and Amitabh Bachchan’s Emergency-era, working-class, angry young North Indian man (as Ashis Nandy has insightfully noted). Finally, the masochistic romantic relationships of Devdas are echoed in films such as PREM ROG (Raj Kapoor, 1982) and many others that depict lifelong, but socially thwarted, passions. Although he has become the very model of the ardent lover whose passion is never consummated, Devdas has nevertheless spawned a school full of sad children throughout the history of Indian cinema.

Suchitra Sen and Dilip Kumar (1955)

The basic plot of Devdas has remained fairly consistent throughout its various incarnations, and in bare outline it hardly explains the story’s ongoing fascination. The rich brahmin zamindar’s devilish son Devdas and the middle-class Parvati (affectionately called Paro) are childhood playmates who declare their love just before Devdas is sent away to Calcutta (or, in the most recent version, England) for his education. After the young couple are reunited (Paro’s brother-like playmate “Dev-da,” the novel notes, becomes “Devdas-babu”), Parvati’s family attempts to arrange her marriage to Devdas, but the latter’s father rejects the union. Paro’s family are lower status, a trading family, and unfortunately, neighbors, and the girl’s insulted family responds by quickly arranging her marriage to a wealthy widower with grown children. Though promised to another, Parvati, in one of the story’s now-famous set-pieces, risks her reputation by coming to Devdas in the night and asking him to save her from a loveless marriage; the weak-willed Devdas hesitates, and decides that he cannot challenge his family and tradition. He is, however, distraught in his decision and, back in Calcutta, seeks to lose himself in drink and the seductive urban demi-monde when his worldly college chum Chunnilal takes him to a brothel. There he meets the dancing prostitute Chandramukhi, who will fall in love with the glum young man who pays yet seeks nothing from her. Three key events carry the story to its hopeless conclusion: Devdas writes Paro an insincere letter denying his love for her, which he attempts but fails to prevent from being delivered; prior to her wedding, Devdas, breaking a childhood promise never to hit Paro again, scars Paro’s beautiful face (originally with a fishing rod), marking her with a symbol of his enduring love (and a punishment for her vanity); finally, as he sinks into greater oblivion despite Chandramukhi’s attempts to care for him after she abandons her profession, Devdas takes a last, aimless train ride across India. Finally, as he had promised (“If it’s the last thing I do, I’ll come to you”), Devdas drags himself to the entrance of Parvati’s home – to which she has been restricted — where he dies just before she is alerted to the presence of a stranger’s body just beyond the massive gates that shut her inside as she runs to him. (While these details may spoil the story for a first-time viewer, it’s clear that most Indian viewers come to any telling of the tale with the plot well-known and its now-familiar highlights eagerly anticipated with each retelling.)

Shah Rukh Khan as a London-returned Devdas (2002)

As a narrative centered around love in separation (viraha), Devdas evokes the story of Krishna and Radha, an echo made explicit in Bimal Roy’s film when, replicating a scene from the novella, Paro pays a Vaishnava couple (replacing three women in the text) with three rupees she is holding for Devdas; whereas in the novel “The songs, their meaning, all passed Parvati by” (though they have an emotional impact), the film trusts that the song – recounting Radha’s longing for the absent Krishna – grounds this story in Hindu tradition and myth. Yet at the same time, the character of Devdas is explicitly “modern” in terms of his education and dress when he first returns from college; the novel outfits him in “foreign shoes, bright clothes, a walking stick, gold buttons, [and] a watch – without these accessories he felt bereft.” More significantly, Devdas is a modern thinker, especially in his challenge to (at least the idea of) arranged marriage, in his cigarette smoking (which in the film versions replaces the novel’s hookah), in his addiction to the “Western” vice of alcohol, and in his bohemian attraction to the nether-world of brothels (aided by the cosmopolitan but irresponsible Chunnilal). As critics have noted, the movement between the village and the city, the story’s cycle of departure and return that abets the young man’s descent, is also fundamental to the experience of Indian modernity, and the consequent alienation from tradition. As such, the hero’s perhaps attractive rebellion is offset by his continually emphasized weaknesses: he is spineless, cruel, narcissistic, and a virtual Hindu Hamlet in his frustrating inability to act, especially when action seems most necessary. The role is then a complex one for a film “hero,” at least in the decades before the “anti-hero” redefined the qualities of the protagonist in the 1970s. While many “feel-good” Hindi films celebrate the careful balance of tradition and modernity – for instance in recent films where arranged marriages and love matches happily cohabitate – Devdas dramatizes the tragic inability of tradition and modernity to achieve balance: the home and the world (to evoke the paradigmatic title of Tagore’s famous novel) are the story’s ultimate tragic couple.

The now-iconic figure of Devdas also might be read as the ritual sacrifice of the young Bengali brahmin to European romantic aestheticism, transporting the sorrows of young Werther-ji into the subcontinent. As noted above, the appeal of that doomed figure, whose self-loathing might express a young audience’s milder frustrations and inability to reconcile cultural demands and individual desires, continued at least into some of the manifestations of Amitabh Bachchan’s angry young man, who nevertheless was more often motivated to fight back, even in vain, than to wallow in passive self-pity. For many viewers Devdas, no matter which charismatic star embodies him, will remain a difficult character to like or admire, but the character demands emotional identification rather than moral emulation; this ambivalent attraction may be exactly what was radical about the original character for at least a generation of Bengali artists and readers. As a self-absorbed, selfish character who is by no means too good for this world, Devdas cannot adjust his damaged ego to what Freud would call the reality principle; indeed, part of the figure’s modernity is in his being defined by an individual ego rather than a class or caste-based morality, a difference that makes traditional heroes appear as unrealistic ideals rather than the type of young man one could actually imagine encountering on the streets of Calcutta in the early decades of the 20th century. Whether the modernist figure of Devdas continues to retain its appeal and relevance for contemporary Indian audiences and postmodern, globetrotting NRIs may be central to evaluating the most recent version of the story.

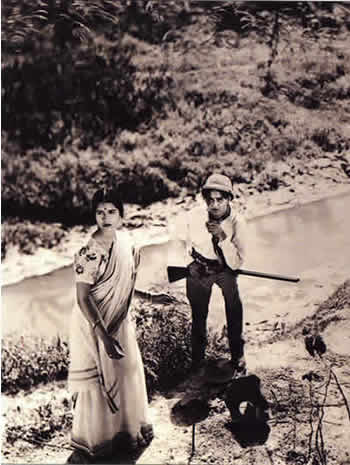

Production still from Barua's DEVDAS (1935)

P. C. Barua’s Hindi version of Devdas, with cinematography by the young Bimal Roy, is one of the most important films in Indian cinema history, though modern audiences will probably find Barua’s film “primitive” and Saigal’s performance stilted (with carefully enunciated Hindi that always sounds quoted rather than spoken), but for its time the film is quite remarkable and formally inventive, using songs and voiceover dialog, for instance, in ways that were innovative for early sound cinema. And many enduring fans will attest that Saigal’s “evergreen” songs have not lost their power and appeal. Unlike the novella, or Bimal Roy’s own remake of the film he first photographed, Barua’s Devdas does not introduce his main characters as children, but as naïve young adults; Barua, however, does suggest that, the title aside, this is largely Paro’s story, as she introduces the narrative. Despite the title of most “official” versions, the story of Devdas is always the story of the doomed relationship between three pivotal characters, and most of its filmed versions take advantage of film techniques to emphasize the deep, almost supernatural ties between them. Critics often cite the film’s use of parallel editing, most notable when, late in the story, Devdas cries out and the film cuts to Paro stumbling, then back to Devdas falling in his train car. Whether this device was Barua’s innovation is hard to determine, but its use of a distinctly cinematic technique to suggest a “telepathic” connection between the separated lovers remains powerful. [Note: Barua's film is not presently, to my knowledge, available on DVD.]

Fom Bimal Roy's DEVDAS (1955)

Perhaps the best-known version of Devdas was produced in 1955, and directed, again, by the cinematographer of Barua’s 1935 films, Bimal Roy, who had recently established himself as a notable Bombay-based director and producer working in a realist style with DO BIGHA ZAMEEN (1953). Most memorably, his version provides indelible performances by Dilip Kumar, Vyjayantimala (originally from South India) as Chandramukhi, and Suchitra Sen (from Bengal) as Parvati. At first glance, Roy’s version of the story seems subtle and naturalistic, with affinities to the emerging Bengali art cinema of Satyajit Ray: the actors are restrained and convincing, and often placed in realistic locations rather than the studio sets which provide the stylized background for other versions. But closer examination reveals that Roy’s film is formally intricate without calling attention to its techniques.

Following the novella, but also picking up on what had by then become something of a tradition in Hindi films (such as ANMOL GHADI or AWARA, among many others), Roy introduces his protagonists as children and will carry them to young adulthood through a transitional dissolve, in this case by focusing upon the richly condensed image of a closed and then open lotus in the river where Paro gathers water, an image that suggests the girl’s “blossoming” as well as the cyclical revolutions of nature, and with an object that moreover connotes the nation. Roy also makes careful, meaningful use of his restlessly moving camera throughout the film. When the boy Devdas calls Paro from her room by tossing stones at her window, a graceful crane shot travels with her from an upper floor to the gate where she meets Devdas below. Years later, when Devdas has returned from Calcutta, the shot replicates itself exactly without much fuss, so that the film itself suggests a basic, enduring relationship despite the passing of years, and the embodiment of the characters by a different set of adult actors.

A moving camera also underlines a key scene, when Paro and Chandramuki – ostensible rivals but sisters in their doomed passion – view one another on the road. In the original novel, the two central female characters never meet, but filmmakers have been unable to reconcile themselves to their complete isolation from one another. While the most recent version of the story allows its superstar heroines to indulge in considerable female bonding, Roy’s film merely suggests this possibility through a quiet but formally powerful moment.

Most recently, Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s extravagant 2002 release starring Shah Rukh Khan as Devdas, Ashiwariya Rai as Paro, Madhuri Dixit as Chandramukhi, and Jackie Shroff as Chunilal is said to be the most expensive production in Indian film history. Although the original context for Devdas is specifically early 20th-century Bengal, the persistent return to the character and story throughout Indian popular culture suggest that they have become archetypes with broad application and appeal. But Bhansali’s film, presented as an explicit tribute to Chattopadhyay, Barua, and Bimal Roy, also suggests that the relevance and appeal of Devdas may be fading into the historical past; his elaborate sets and costumes render the historical past as spectacle rather than as artifact, and so his early 20th-century Calcutta resembles an elaborate fantasy rather than a lost, recreated time and place. On its surface a rather simple story, in this recent incarnation Devdas has become operatic, or, less generously, overblown.

Bhansali’s film is an opulent, extravagant spectacle, filled to the brim with elaborate sets and stunning costumes, and it is often shot with breathless, rushing steadicam shots of swirling action and color. The soundtrack pounds away with thunderous beats at every emotional high or low point. As Anup Singh suggests, the director’s aim seems to be to render the story’s strong emotions through the film’s hyperventilating style as well as the situations of the characters. But this abundance – if this is indeed India’s most expensive film to date, the money, as they say, is on the screen – constantly threatens to overwhelm what remains at heart a simple, if psychologically complex, story.

Vyjayantimala as Chandramukhi, Motilal as Chunnilal (1955)

It is not mere nostalgia that makes Roy’s version seem preferable, and near definitive, but its realistic grounding despite adherence to Bombay conventions: Devdas is, again, less a classical tragic hero than a modernist anti-hero, whose downward spiral does not occur in a mythic space, but in the historically specific modern world which, lowering the standards of genuine tragedy, can no longer support the grand gesture or heroic sacrifice of mythic heroes. The persistent echo of the divine (yet lustful) love of Krishna and Radha in the Devdas story is thus as mocking as it is sustaining: while the devotion of Devdas and Paro may be unbreakable, they are after all not immortal gods, and so the world breaks them despite their passion, reducing them to the human status of the doomed Romeo and Juliet rather than elevating them to the realm of the eternal lovers of Hindu myth.

Bhansali’s film places its characters within a modernity that is now so far past that it must be artificially overstated, as Devdas’s arrival in now-comic early 20th-century Western fashion (including a monocle and cigarette holder) emphasizes for a short while. Thereafter, the film’s setting is taken over by the elaborate sets which compete with the story and characters for the audience’s attention. The film is thus neither updated (by, for instance, making Devdas a drug addict rather than an alcoholic) nor genuinely historical, techniques which might have forced the audience to compare its present situation to the represented past. By creating a fantasy space with only slight reference to the real world or historical context – the film generally avoids specifying its time or place directly – the film constructs a fantastic vision of a romantic “Bengal” that may be as exotic for the film’s (North) Indian audience as for its diasporic (and non-Indian) viewers. (If, for instance, the film is obviously favoring the “modern” love match over the traditional arranged marriage, then the return of the arranged marriage in so many of the mega-hit family films of recent years suggests that the “modern” position can hardly be assumed for contemporary viewers.)

Moreover, this version’s decision not to first depict Devdas and Paro as children, except later, in brief flashbacks (with Devdas hardly depicted at all), tends to take the story out of a tradition – developed in part by earlier versions of this story and associated works – of presenting true lovers as recognizing one another even as children, whose passion never “grows up” or adjusts to the pressures of class, caste, or economic realities. While the childhood infatuation of Devdas and Paro is frequently described in dialog, the avoidance of the characters as children – in part, I think, an effect of Shah Rukh Khan’s prominent boyishness in his screen persona – makes their lifelong love and Devdas’s Krishna-like mischief something we must trust upon hearing from others rather than something we are given to witness. The lifelong attachment of Devdas and Paro is richly grounded by the first sections of Bimal Roy’s film, whereas Bhansali trusts that mere reference to their childhood devotion will suffice.

Although it might be argued that none of the stars of the latest version of Devdas were capable of carrying the weight of these now-legendary roles, the film has the odd effect of its actors improving as the film proceeds. Shah Rukh Khan achieves some of the gravity of his character once the boyish qualities that have defined him as a star are no longer appropriate, and Aishwarya Rai – for the first half perhaps the dimmest Paro in the story’s tradition – seems to perceptibly gain increased knowledge of, if no control over, the social forces defining her. (As depicted in earlier versions, Paro is a simple but by no means stupid girl, and so Aishwarya Rai’s emphatic naivete seems a disservice to the character: the fact that she actually keeps a candle burning for Devdas implies a too-literal mind as well as devotion.)

Madhuri Dixit, here playing a “mature” character now that she is an “older woman” by Hindi heroine standards, provides the film’s standout performance, and constructs perhaps the single character whose feelings seem genuine throughout; an elaborate song-sequence in which she and Paro interact (to an extent unprecedented in earlier versions) is unexpectedly effective in demonstrating Chandramuki’s basic goodness, undeserved abjection, and passionate drive, all registered through Madhuri Dixit’s expressions and postures. As the unwitting aide to Devdas’s self-destruction, Jackie Shroff, in a cameo as the unintentionally destructive Chunnilal, is also memorable. Yet even these worthy performances must continually compete with the film’s dazzling – but ultimately distracting – costumes and scenery, all again presented through a hyperactive camera and unrelenting soundtrack. As with each previous version of the story, this film’s strongest moments are in small details and gestures, but the film itself seems to have been made with the mantra that “size matters” as it persistently boosts and trumpets many of its otherwise most delicate moments.

Although Bhansali’s film was a commercial hit that played in major cinemas worldwide (I saw it in a massive cinema in London’s theatre district, where it was widely advertised alongside mainstream British and American films), its long-range impact seems less certain than that of previous versions of the story. (The apparent attempt to make this the film to finally bring “Bollywood” to Western audiences also seems a failure: the smaller non-Bollywood films MONSOON WEDDING and BEND IT LIKE BECKHAM have reached far more Western viewers, who often mistake such “international” films for the real thing.) Whether the myth of Devdas maintains its power into the 21st century remains to be seen, but one suspects that yet another version – probably in the now-established tradition of unofficial remakes – will be necessary to revitalize the tale for contemporary audiences, in the way that Bachchan’s unexpected channeling of Devdas in some of his 1970s roles clearly shook up the norms of Indian popular cinema. In any case, the story of a young man who dies too young has seemed immortal for most of the 20th century; ironically, his latest incarnation seems to hasten his legend’s demise rather than sustain it.

[The films on DVD: As noted above, the 1935 Hindi version of Devdas is only currently available on unsubtitled, mediocre-quality videotape. The Yash Raj Films DVD of the 1955 DEVDAS in their Bimal Roy Collection is of good but not superior quality; it features complete subtitles and also includes an illuminating interview with Dilip Kumar by Nasreen Munni Kabir and “Images of Kumbh Mela,” unedited footage shot by Bimal Roy before his death. The Roy film is also available in a Baba Traders edition with image quality roughly comparable to that of the Yashraj version, but with no subtitles for songs. A slightly superior print of the film, and with subtitles for both dialog and songs, is available from Shemaroo Ltd., which owns the Indian distribution rights for the DVD; though technically illegal in the West, Shemaroo copies occasionally turn up in Indian shops and on DVD websites. The Eros DVD of Bhansali’s 2002 DEVDAS is available in an excellent version with complete subtitles as part of an – unsurprisingly – lavish two-disc box set which includes souvenir postcards and an extra disc of “special features” including entertaining but insubstantial documentaries and interviews with the film’s stars and director.]

Printed sources:

The first complete English translation of Saratchandra Chattopadhyay’s Devdas by Srejara Guha with Guha’s helpful introduction, was published by Penguin Books India in 2002. It should supersede the abridged version translated by V. S. Naravane included in Sarat Chandra Chatterji, Devdas and Other Stories, New Delhi: Roli Books, 1996.

Both the 1935 and 1955 film versions of DEVDAS have received considerable critical attention: see, for instance, Ziauddin Sardar’s wonderful essay “Dilip Kumar Made Me Do It,” in The Secret Politics of Our Desires: Innocence, Culpability and Indian Popular Cinema, ed. Ashis Nandy (London: Zed Books, 1998): 19-91. Other discussions of DEVDAS appear in Kishore Valicha, The Moving Image: A Story of Indian Cinema (Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 1988): 43-60; and in Ashis Nandy's essay, “Invitation to an Antique Death: The Journey of Pramathesh Barua as the Origin of the Terribly Effeminate, Maudlin, Self-Destructive Heroes of Indian Cinema,” in Pleasure and the Nation: The History, Politics, and Consumption of Public Culture in India, ed. Rachel Dwyer and Christopher Pinney (New Delhi: Oxford UP, 2001): 139-160. Asjad Nazir’s essay “The Changing Faces of Devdas,” in Eastern Eye (London) 5 July 2002: Emag 8-9 is a brief overview of almost a century of the story’s retelling; a more detailed overview can be found in P. K. Nair, “The Devdas Syndrome in Indian Cinema,” Cinemaya 56/57 (Autumn-Winter 2002): 82-87. The same issue also includes Anup Singh’s “Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas and the Intensity of the Self,” and Faria Etem’s “Seen from Bangladesh: No Borders for Devdas.” A recent volume, largely in celebration of the 2002 film but containing useful informaton, is Devdas: The Eternal Saga of Love, edited and compiled by Rahul Singhal (Delhi: Pentagon Paperbacks, 2002). Gayatri Chatterjee relies on the 1935 Devdas in order to illuminate Raj Kapoor’s classic film in her close analysis Awaara (New Delhi: Wiley Eastern Ltd., 1992; rpt. New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2003), and Ravi Vasudevan uses a key scene from the 1955 Devdas to illustrate the Hindu practice of darsana (or darshan ) in “The Politics of Cultural Address in a `Transitional’ Cinema: A Case Study of Indian Popular Cinema,” inReinventing Film Studies, ed. Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams (London: Arnold, 2000): 130-164.]