DILWALE DULHANIA LE JAYENGE

(“The lover takes the bride”)

1995, Hindi, 190 minutes

Directed by Aditya Chopra, Produced by Yash Chopra

Story – screenplay: Aditya Chopra; Dialogue: Javed Siddiqui, Aditya Chopra; Music: Jatin-Lalit; Lyrics: Anand Bakshi; Cinematography: Manmohan Singh

Remember when the West was a threatening place, where Indians perforce went to make money, but then the men surrendered their culture and the women their modesty? (In case you don’t, the trope may be seen at full tilt in PURAB AUR PACCHIM, 1970; it remains alive and kicking in recent films like PARDES, 1997). DILWALE, or “DDLJ” as the Indian-English press collapsed its unwieldy title, initially appears headed down the same road—as a sour-faced Chaudhury Baldev Singh (Amrish Puri) feeds pigeons in Trafalgar Square while yearning for the green fields of “my land, my Punjab”—but then takes a number of surprising and refreshing turns. These may have helped it to not only top the box office in India (where it also won a pack of Filmfare awards), but to become a huge hit among Indian communities overseas, to whom it finally gave some positive recognition. Its different take on globalization and the diaspora, fine performances by the bouncy Shah Rukh Khan and the feisty and radiant Kajol, and superb medley of songs make this one of the most appealing of the romantic “family” films of the 1990s.

Baldev Singh, who still feels himself an unwanted stranger in his adopted land and fears and abhors its ways, runs a petrol pump and mini-market in London and lives in a tidy suburban row house with his wife Lajjo (Farida Jalal) and two daughters. The elder, eighteen-year old Simran (Kajol) has been raised in the UK and dreams of romance with a stranger-of-choice (picturized in the song Mere khwaabon men, "The one who comes in my dreams"), but Dad has his heart set on an arranged match, promised twenty years earlier, with the son of his best friend Ajit back home.

When he sternly reminds Simran of this, she glumly accepts her fate but pleads for a month’s recess, to join some girlfriends on a last fling: a rail tour of the continent—in a rare beneficent mood, Dad agrees. Enter Raj (Shah Rukh Khan), the fast-talking, fast-track son of Indo-British millionaire Dharamveer Malhotra (Anupam Kher), with whom he has an unusually chummy, beer-chugging relationship—all portrayed with apparent approval. When Raj fails college (a family tradition, his “Pops” informs him) he too embarks on a month’s holiday in Europe with some buddies, naturally, on the same train as Simran and her girlfriends.

The rest of the pre-interval segment is devoted to gradually getting Simran over her initial aversion to the overbearing, self-centered Raj (some viewers may feel she had it right the first time); this involves their getting separated from their companions in deepest Switzerland, a drunken cavort in a pool and snowfield (Simran gets drunk on cognac, and this too is permissable), and a near-sexual encounter that, naturally, stops short of compromising Simran’s virginity. Before the group returns to London, Simran realizes that Raj’s brash exterior conceals (a) heaps of musical talent (already a good sign), (b) tons of heart (getting warmer), and (c) True Love for her (bingo). When she confesses this to her mom, Dad overhears and flies into a rage. He packs the family off to India, for keeps, the very next day.

Part Two focuses on the protracted collision between the irresistible force of Raj and Simran’s love (which grows more plausible and appealing as the film progresses) and the immovable object which is Baldev Singh; Puri gets many opportunities to deploy his patented bulging-eyed glare, but also to show some humanizing chinks in the patriarchal armor. Though India is predictably idealized (just as Baldev remembered, there are vast fields of blossoming mustard amidst which pastel dupatta-ed damsels dance in perfect synch, and his friends and relatives live in mansions and appear not to work), the fiancé, Kuljit, proves less-than-perfect: a brawny and rather brainless Punjabi Hindu Princeling who accepts Simran as His Due, but is already thinking about future babe-conquests—plus he drinks more beer than Raj and even shoots pigeons.

Raj turns up and cleverly insinuates himself into the family, gradually winning over nearly everyone except Baldev. Though the story adheres to the convention of asking Simran to wait patiently while the menfolk sort out her fate, Kajol brings great spirit to the role and manages, especially through several conversations with her mother and sister and a remarkable manipulation of the women’s festival of Karwa chauth (when women fast until moonrise for the benefit of their husbands), to signal her inwardly steely resistance. She also demands, and gets, treatment from Raj that suggests a companionate and egalitarian future relationship for the two. But there is still the problem of her being engaged to someone else, and Raj’s steadfast refusal to elope: he is a “Hindustani” after all, and insists that her father willingly “give” her to him. Achieving matrimonial freedom of choice for the younger generation while ostensibly upholding patriarchal authority and control is a clever trick, and though a feel-good ending is a foregone conclusion, the director keeps us guessing as to how he will pull it off.

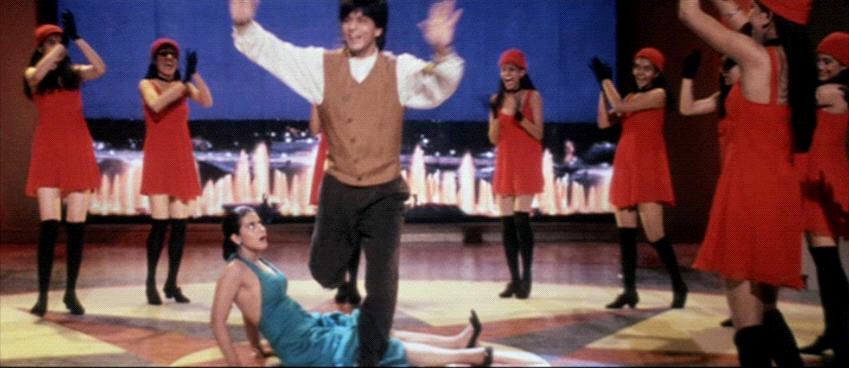

Eight strong songs include numerous standouts: the lilting and thrice-reprised Ghar aaja pardesi (“Come home, wanderer”), the frenetic Ruk jaa, o dil diwane (“Stop, O my mad lover”), performed by Raj in an imaginary Paris nightclub, the lovesong Tujhe dekha to (“When I saw you, I realized…”), and the splendidly-choreographed Mehndi laga ke rakhna (“Make sure henna is applied to your hands”), sung by the wedding party in a rooftop romp.

For teachers, this could be a good film to stimulate discussion of inter-generational issues and changing cultural values in the Indian diaspora (especially if paired with one of the more stock portrayals noted earlier, or with the British independent film BHAJI ON THE BEACH). DDLJ has been the subject (together with PARDES) of an insightful journal article by Patricia Uberoi (see abstract below).

Patricia Uberoi, “The Diaspora Comes Home: Disciplining Desire in DDLJ.” Contributions to Indian Sociology, vol. 32, no. 2 (1998), pp. 305-336.

ABSTRACT: “A significant new development in the field of Indian family and kinship is the internationalisation of the middle-class family. The author analyses two popular Hindi films of the mid-1990s, Dilwale dulhania le jayenge (DDLJ) and Pardes, that thematise the problems of transnational location in respect of courtship and marriage. The two films share a conservative agenda on the family, but differ in their assessment of the possibility of retaining Indian identity in diaspora. DDLJ proposes that Indian family values are portable assets, while Pardes suggests that the loss of cultural identity can be postponed but ultimately not avoided. These discrepant solutions mark out Indian popular cinema as an important site for engagement with the problems resulting from middle-class diaspora, and for articulation of Indian identity in a globalised world."

[For unknown reasons, Yash Raj films delayed authorized release of this hugely popular film until 2002, and pirated copies on DVD and VHS (some of decent quality, with subtitles) are in wide circulation. However, the official release is of superior quality, and has subtitled songs. It also includes a second disk with various extras for hardcore fans.]