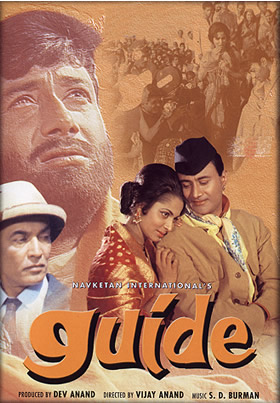

GUIDE (1965)

Hindi, color, 170 minutes.

Directed by Vijay Anand. Music by S. D. Burman.

The Anand brothers ambitious adaptation of R. K. Narayan's novel is a lush allegory comprising paradoxically-paired themes of, on the one hand, nation-building, modernization, and social reform, and, on the other, world-renunciation and spiritual self-realization -- all enduring preoccupations of contemporary Indian culture. Dev Anand stars as the effervescent Raju, a fast-talking, self-promoting tourist guide in the Rajasthani city of Udaipur, who in time becomes the successful promoter of his dancing-girl mistress, and ultimately (through his accidental transformation into a "mahatma" worshiped by illiterate villagers) of himself -- or rather (in deference to the filmmakers' neo-Vedantic ideology) of the unitary, absolute Self. This trajectory is shaped through two narratives that come together in the film's final moments: a frame story about Hindu concepts of the power of faith and renunciation, involving an ex-con who is mistaken for a saint and gradually grows into the role, and the emboxed narrative (comprising the bulk of the film) of the unhappy dancer Rosie (Waheeda Rehman), whom Raju guides away from a loveless marriage to the archaeologist Marco (Kishore Sahu), and into the role of the acclaimed "classical artiste" Nalini.

The heroine's name change is heavily suggestive, since her English nickname carries the tawdry overtones of the demi-mondaine world of the traditional tawayaf, devadasi, or (in colonial lingo) "nautch girl" -- a courtesan learned in dance, music, and poetry, often "married" (if Hindu) to a temple deity, and permitted to perform in public (as respectable women were not), and to form casual liasons with mundane men; she was symbolically auspicious but socially tainted. In the film, Rosie's mother clearly still belongs to this vanishing subculture (for other tawayaf films, see notes on PAKEEZAH and UMRAO JAAN). The transformation of such a woman into a delicate lotus (nalini), the Indian national flower and symbol of chaste purity that rises above the mud of the world, offers an astute rhetorical and cinematic allegory for the historical process whereby Indian "classical dance" (comprising Bharat Natyam and other regional styles) emerged in the twentieth century as a re-invented tradition, purified of its associations with nautch girls and brothels, championed by nationalists and self-styled "social reformers," and eventually lionized by the urban bourgeosie (and taken up by their daughters) as an emblem of "national culture." With relevance to the film world itself, Rosie's transformation also powerfully recalls thetawayaf roots and struggles for respectability of major film actresses like Nargis, Meena Kumari, and Rehman herself. Yet the successful Nalini/Rosie, perhaps haunted by the suffering she has endured, remains deeply unhappy. Her neglect and distrust of her benefactor, Raju, leads to a breakdown of communication between them and her eventual turning against him when it is revealed that he has forged her name on a check.

The film is strongest on the inception of their relationship, when Raju slowly becomes aware of the depth of Rosie's sorrow and of the abuse she receives from the rich Mr. Marco, to whom her mother married her in a desperate bid for respectability -- a sour antiquarian who lusts after stone images of copulating couples while despising his own voluptuous young wife. Raju gradually begins "guiding" Rosie to belief in herself and in her talents, eventually giving her shelter in his home despite the voyeuristic scandalization of his neighbors and the outraged opposition of his relatives (Leela Chitnis portrays another long-suffering widowed mother). Raju's courage and compassion, and the hypocrisy of "respectable" society's attitude toward "public women" are powerfully portrayed, as is the chemistry between him and Rosie. Their later falling out, at the height of Rosie's success, is rendered more sketchily -- the film implies (in contradiction to its earlier message), that worldly success inevitably corrupts and that career women must indeed construct (in Rosie's words) "a sort of fortress around the heart." Raju's hurt over this rejection helps to drive him to melancholia, booze, and gambling; a lingering jealousy of the rich Mr. Marco (whose surname Rosie still bears) prompts his fateful act of forgery.

Along the way, there is much superb dialog (mostly lost, alas, in the crude and often garbled English subtitles) that uses Raju's code-switching skills to sharply-ironic effect: as when the bogus holy man trumps unscrupulous village Brahmans by responding to their Sanskritshlokas with an incomprehensible speech in the new father tongue of Command -- English; and when the slick dance promoter uses Sanskritized shuddh Hindi to convince school officials that a Bharat Natyam performance will help their charges resist degenerate Western jazz and pop. There is also wonderful music -- R. D. Burman's notable score comprises nine songs, most of which became hits -- and gorgeous cinematography that takes full advantage of the primary colors and rugged monuments of the Rajasthani landscape. The film's return to its frame narrative may strike some viewers as jarring, for the filmmakers clearly decided on a less-ambivalent portrayal of the conman-turned-saint than is found in Narayan's novel. This decision is already hinted at in the film's opening, when the paroled Raju makes the choice not to return to his home city and instead takes up a wandering life. During the credit sequence, we see him roaming through India, homeless and penniless, his Western clothes gradually falling to tatters and yielding to village khadi (homespun cotton), while a voiced-over wayfarer's song offers lyrics reminiscent of the antinomian nirgunadevotion of medieval poet-saints like Kabir.

In the final sequence, the film acquires overtones of the much-maligned mythological/devotional genre (at one point, the voice of God speaks from a penumbra of light, and the climactic moments recall Damle's 1936 classic Sant Tukaram), and its validation of the simple faith of the villagers may appear, in a materialist reading, as a cynical sop to India's most powerful opiate. But other readings are certainly possible and, perhaps appropriately, how one feels about the transfigured Guide at film's end may ultimately depend on how one feels about the One.