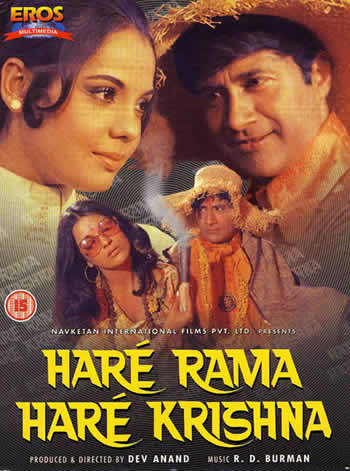

HARE RAMA, HARE KRISHNA

1971, Hindi, 140 minutes

Produced, written, and directed by Dev Anand

Music: Rahul Dev Burman; Lyrics: Anand Bakshi; Art Direction: T. K. Desai; Cinematography: Fali Mistry

The late 1960s and early ‘70s witnessed a weird new “invasion” of India—not by Central Asian or British empire builders, but by youthful, longhaired “refugees” from the rich and powerful First World nations that elite India was striving mightily to emulate. Middle class Indians, still accustomed to Nehruvian five-year plans that limited consumer goods to the meager products of indigenous industry and yearning for the imagined good life that lay beyond the Black Waters, reacted with dismay, derision, and general bewilderment to these new strangers in their midst, who came not as five-star-hotel tourists but as low-budget pilgrims out to experience “authentic” Asian life—amoebas and all. They often arrived via seedy overland buses that crossed Europe, Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan to disgorge their loads of bottom-end travelers at the doorsteps of Old Delhi flophouses and hashish dens—usually as mere stopovers enroute to Kathmandu where (as conventional wisdom had it) “the hash is better and the people don’t hassle you.” Why, wondered puzzled Indian observers, were the sons and daughters of the postindustrial West affecting the look of Bombay pavement dwellers or (worse still) anti-social sadhus, wearing soiled clothes and grubby sandals, sleeping on charpoys, and smoking charas? There was even the fear, at least among the upper echelons of the middle class, that such bad behavior might infect the sons and daughters of Hindustan. The hippies’ drug use and advocacy of “free love” was appalling to Indian bourgeois values, and their confused appropriation of Hindu ideology and symbolism was likewise a source of embarrassment and alarm. Yet paradoxically, their admiration for the supposedly superior spirituality of the East (manifest in the successful Hindu “missionary” activities of globetrotting swamis like A. C. Bhaktivedanta, whose ISKCON temples and processions in major western metropolises were widely reported in Indian media) was also a source of a certain grudging pride—since spirituality continued to be seen as one of the (few) things that India was really good at manufacturing.

The hippies’ mecca of Kathmandu in neighboring Nepal also acquired special notoriety during this period, and for a variety of reasons. Imagined (not entirely wrongly) as the epicenter of their orgiastic behavior, it attracted the longing gaze of (especially) Indian men, titillated by the prospect of scantily clad, drug-crazed blonde nymphets giving themselves freely to a range of casual comers on. Moreover, this was but a new wrinkle on a classical trope, for the fantasy that the folk who live beyond the Himalayas have looser morals and less inhibitions, and that their womenfolk exercise freer agency in their choice of partners—a standard that invites both opprobrium and envy from those who see themselves as more constrained by strict dharma—has a history that dates back to ancient Sanskrit literature. This has long led to a certain exoticization of the Nepali Other—a kind of homegrown Indian orientalism, focused on a mountain Hindu kingdom where (it is said) even Brahmans eat meat, drink alcohol, and have a proclivity for tantric rituals. Moreover, during the latter days of Congress Raj, when India’s imports were still severely restricted by protectionist trade barriers and the middle classes were enjoined to practice Gandhian austerity, this fantasy was augmented by the fact of Nepal’s freer economy, which made Kathmandu an alluring bazaar of much-desired foreign consumer goods, especially East Asian electronics and watches (considered to be far superior to the equivalent Indian products), clothing, and liquor. The imagined lifestyles of the transnational rich, carried out poolside and in the discotheque of Kathmandu’s five-star Soaltee Oberoi Hotel, added another layer to the complex fantasy of a trans-Himalayan realm of forbidden pleasures—so near, and yet so far beyond the means of the average Indian.

These intertwined discourses about alluring and threatening Others—hippies, Nepalis, and the ultra-elite of wealthy, jet-set Indians (the label “NRI” had yet to be invented)—come together in Dev Anand’s lurid and chaotic period piece, which became the classic Bombay cinematic statement on the counterculture phenomenon. Indeed, throughout the 1970s, street urchins in Indian towns were apt to greet young Western travelers with a mocking rendition of the film’s hit title song (whose chorus utilizes the Bengali Vaishnava and ISKCON chant of “Hare Krishna, Hare Ram” but which is more generally known, following standard Bombay practice, by its opening line, “Dum maro dum,”—“Take another toke!” In the film’s soundtrack, it is seductively performed by Asha Bhosle). Shot mostly on location in Kathmandu with dozens of real-live hippie extras, the film proffers a titillating inside glimpse of stoned-out life brokered through the time-honored cinematic trope of the self-turned-Other: a cultural insider who has gone “native” (c.f., Brad Pitt in Seven Years in Tibet). In this case the turncoat is a Canada-raised Indian girl, Jasbir Jaiswal (Zeenat Aman), whose India-raised brother Prashant (Dev Anand), an airline pilot, is trying to rescue her from her adopted hippie “love family” in a Kathmandu commune called “The Bakery.”

Since the hippies’ implicit (if selective) critique of Western materialism was mostly incomprehensible to middle class Indians, standard explanations for their bizarre behavior centered around the notion that they were “lazy” youth, the product of morally lax upbringings, who were “running away” from worldly responsibilities, and whose minds had become unhinged through psychedelics and promiscuity (this was not, of course, an altogether unfair assessment in some cases). But whatever would induce an Indian girl to succumb to this wastrel lifestyle? The film explains this through a long flashback set in a soundstage Montreal, where snowflakes swirl around obviously fake skyscrapers, and where Prashant and little Jasbir (played by Master Satyajit and Baby Guddi) share sibling love (celebrated in the cute song Phoolon ka, taron ka, “The flowers and stars [all say that my sister is one in a thousand!]”), while dodging the crossfire of their feuding parents (Kishore Sahu and Achala Sachdev). As in other films of the period that feature overseas Indians (for example,Purab aur Pachhim), Western living is shown to have taken a heavy toll on the Jaiswals: Mr. J. has a mistress, Mrs. J. drinks and dances in clubs, and they hurl abuse at one another in front of their traumatized children.

When the marriage finally melts down, a Canadian court decides (for unspecified reasons) to give the daughter to the father, who remains in Canada and remarries, while the son accompanies the mother back to India. Each child is told that the other has “died,” but the younger Jasbir, marooned in chilly Canada with a neglectful dad and nasty stepmom, gets the worse deal; her compensatory thumb sucking and guitar strumming hint at the bad habits she will later acquire. Sure enough, sixteen years pass and she falls into unsavory company, steals $5000 from her father’s safe, and flees to Kathmandu under the name of Janice, where she opens a psychedelic boutique with a hippy boyfriend and becomes the presiding spirit of The Bakery’s tribe. It appears, at first glance, that she has a pretty good deal. Though some of her videshi friends look rather wasted (as pasty-faced foreigners tend to do in Hindi films), Janice/Jasbir is, let’s face it, Zeenat Aman, so she is always (even when supposedly doped-out) gorgeous, bubbly, and vivacious, nicely coifed and made up, and stylishly dressed. With several adoring boys in tow, she seems to be having a whale of a time, playing acoustic guitar, smoking charas, and pertly lecturing attentive hippies on Eastern Spirituality 101.

Lest viewers get the wrong idea, grown-up Prashant flies in, tipped off by a cue from Jaiswal senior that Jasbir is still alive and in Kathmandu (which we first admire from the air, when Prashant and a fellow pilot take their commercial jet through a series of don’t-try-this-after-9-11 low passes over the city’s famous monuments). Big Brother will tell us What’s Wrong With This (happy hippy) Picture, but first (being Dev Anand) he will immerse himself in several subplots. He will be befriended by a fast-talking tourist guide named Toofan (Rajendranath) and his simple-minded child sidekick Masina (Jr. Mehmood), who will help him woo the local belle Shanti (Mumtaz). In doing so, he will run afoul of evil landlord Dronacharya (Prem Chopra), who also has his lustful eye on Shanti, when he is not stealing gold idols from the Swayambhunath shrine (a Buddhist complex outside Kathmandu) for sale to foreign dealers. These subplots interweave with Prashant’s incognito pursuit of Janice (who steadfastly denies being Jasbir, and who assumes that Prashant has amorous intentions), in the course of which he flirts with hippie ways (or anyhow, costume) thus displaying his Heroic versatility—though the aging Anand, adorned with love-beads, appears rather out of his element in his own film.

We get to ogle at erotic dancing of the Approved Sort when uninhibited Shanti publicly performs the flirtatious song Ghungroo ka bole (“What do the anklebells say?”), revealing her fancy for Prashant, and of the Disapproved Sort too when half-naked hippies writhe by firelight to Dum maro dum—the full version of this famous song includes Prashant’s song-sermon rejoinder to the wayward youth, Ram ka nam badnam na karo (“Don’t give the name of Ram a bad name!”):

“Understand Ram, know Krishna,

awaken from your slumber, O intoxicated ones.

Conquer your minds by reading the Gita.

Ram relinquished all pleasures with a smile,

but you are fleeing sorrows out of fear.

Krishna taught the way of duty,

but you have shut your eyes to all obligations.

I swear by Lord Ram,

don’t give the name of Ram a bad name!”

In the end, all the plots converge, and even the long-divorced Jaiswal parents turn up in Kathmandu to reunite with their son and be properly distraught over the plight of their daughter. But although stolen idols can be recovered and star-crossed lovers wed, don’t bet too much that 1971 Hindi-film morality will permit the bubbly Janis/Jasbir— a girl who has happily guzzled beer, smoked hash, and (seemingly) slept around—to be fully redeemable, even after she has recovered her familial memory.

The film is predictably awash in psychedelic colors and abounding in the zoom shots that were so favored by directors (and not just Indian ones) at the time. Yet the use of Kathmandu locations and the casting, as extras, of the very people who form its main subject gives Hare Rama, Hare Krishna at times the feel of a tables-turned ethnographic documentary—and this may be, in retrospect, the film’s most intriguing feature—in which anthropologist Anand serves as an Indian eye to gaze at the strange customs of the inscrutable whiteys. As an American who first went to India in 1971 at age twenty, longhaired and kurta-clad, I recognize, beneath the hokey plot trappings, more than a little uncomfortable accuracy in Anand’s portrayal of what was, after all, a very strange subcultural moment on the Subcontinent. To paraphrase Pogo, “Them was us!”

[The Eros Entertainment DVD of Hare Rama, Hare Krishna features a good quality print of the film, and tolerable subtitles—though (as usual with products from this company) none are provided for the songs.]