HEY RAM

("O God!"), 2000. 190 minutes. Color, Hindi (also available in Tamil)

Directed by Kamal Haasan.

Screenplay: Kamal Haasan

Starring Kamal Haasan, Shah Rukh Khan, Rani Mookerji, Girish Karnad, Hema Malini, Naseeruddin Shah.

It's December 6, 1999, and in a Chennai racked by communal violence on the 7th anniversary of the destruction of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya (a Muslim site claimed by Hindu fundamentalists as the "birthplace" of the epic hero-god Ram) a retired archeologist named Saket Ram lies dying of heart disease.

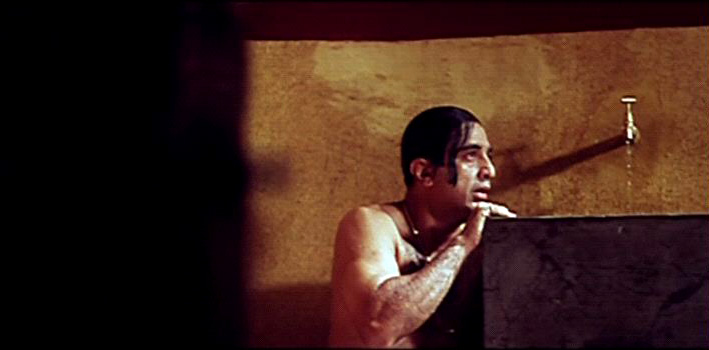

Keeping vigil at his bedside, his grandson, a Hindi novelist, narrates part of the old man's life story to the attending physician — a true story that he implies to be stranger than any fiction. It begins 53 years before, with Ram (Haasan) and a Muslim colleague, Amjad (Shahrukh Khan) working under the direction of British archeologist Mortimer Wheeler in the excavation of a grave in the 4,000 year old Indus Valley city of Mohenjo Daro (the "mound of the dead"). But their painstaking work to uncover the mysterious first urban civilization of South Asia is abruptly cut short by the announcement of the imminent division of the Subcontinent into two nations. Mohenjo Daro will now be in Pakistan, and Ram must return to his home in Calcutta.

So begins famed Tamil and Hindi actor Kamal Haasan's daring and controversial meditation on the violence of Partition and its lingering traumas — a subject virtually taboo in commercial cinema for half a century. While retaining the look and sound of the Bollywood blockbuster (complete with digital special effects and a modest number of songs), Haasan's cinematic epic ventures deep into the terrain of communal conflict, examining the process by which human beings create and destroy their intimate "others."

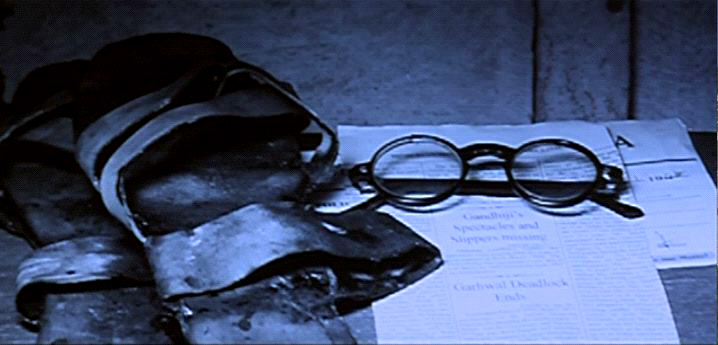

Most of the film unfolds in flashback within the brief span between August 16, 1946, when the future "Father of Pakistan" Muhammad Ali Jinnah's declaration of a day of "Direct Action" by Muslims sparked communal carnage in Calcutta, and January 30th 1948, when a Hindu fanatic's bullet felled the "Father of India," Mohandas K. Gandhi at a prayer meeting in the garden of New Delhi's Birla House. These watershed events shape Saket Ram's personal trajectory and drive him, at times, to the brink of madness. The film offers an unprecedented portrait of a traumatized survivor of events that others seek to forget, and reopens some of India's most painful wounds — though ultimately pointing toward a barely-imaginable redemption.

HEY RAM opened in February, 2000 to a lukewarm response in all but the deep South (where Haasan enjoys superstar fame). The film’s poor reception—or rather, near invisibility—in India partly reflected the reaction of angry politicians and bewildered critics (India Today praised its "technical wizardry" and acting, but called it "hard to categorize"). Many distributors (always jittery about cinematic subjects that are “too controversial” or “too smart” for the audience) pulled it from their areas within days of its release. The right-wing BJP party tried to have it banned as an “anti-Hindutva” film, while some Congress Party leaders denounced it as “anti-Gandhi”—the BJP’s reading appears, to me at least, to have been the more astute and certainly more in line with the director’s stated intent. Some leftist intellectuals, however, complained that the film’s refusal to demonize Hindu communalists and its “seductive” use of their imagery entirely subverted any progressive ideological agenda. If nothing else, such glaringly bi-polar interpretations at least suggest the intentional complexity of this courageous and groundbreaking film about individual and collective madness. As a meditation on Gandhi (albeit one in which he seldom appears on screen), the film offers us a humanized Bapu who is cranky, humorous, and not always sure of himself—a portrayal that I, for one, much prefer to the flat and pontificating Mahatmas of Richard Attenborough (Gandhi 1982) and Shyam Benegal (The Making of the Mahatma, 1996)—whose every utterance appeared ready to be set in granite.

In the great tradition of Indian epic storytellers (and modern Indian magical-realist novelists), Haasan constructs his tale with multiple layers and ironies, involving three principal narratives, two of which are explicit and one implied. The frame narrative of the dying archeologist Saket Ram—a man who made his living digging through layers of the past—anchors the tale in the present (of the film’s release), at the turn of the 21st century. It also invokes (through the symbolic date of December 6th) the rise of Hindu nationalism during the 1990s as a potent force in Indian politics and the attendant increase in communal riots and massacres: events that led many Indians to a re-examination of long-repressed memories of the Partition violence in which their nation was born. As Saket Ram struggles for his life’s breath (muttering, "My nightmares are coming back to me...") the film hints at a nation struggling with its memories in the poisoned atmosphere of religious identity politics that have bred renewed hatred, fear, and violence. Since “Saket” is one of the ancient names of Ayodhya and also the name, among Ram worshipers, of the heavenly and eternal “city of Ram” to which they aspire after death, the hero of the film is also “Ram of Ayodhya,” and his own physical passing (in Hindi devotional euphemism, his “setting out for Saket”) is destined to fall on the anniversary of the day on which the earthly Ayodhya witnessed an act of desecration that would reverberate throughout the Indian body politic.

The second explicit narrative is the flashback that comprises most of the film: a recapitulation of roughly a year and a half of some of the most turbulent and momentous events of 20th century South Asia: Partition and its aftermath, Independence, and the murder of Gandhi. This part of the film is exhaustively researched and fastidiously recreated, and most of the characters depicted (with the exception of the hero) are based on real persons. They are also, of course, archetypes of roles taken by (or forced upon) many Indians during this period:

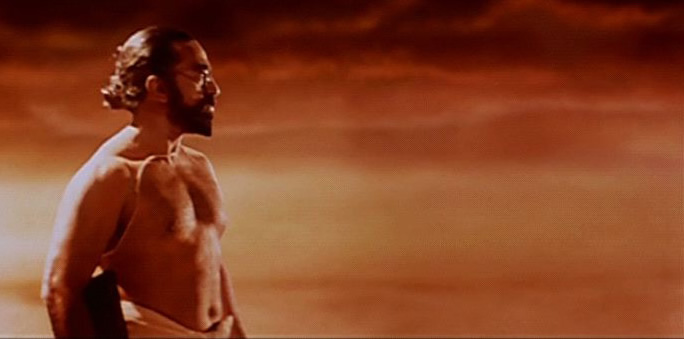

the brahman intellectual Sri Ram Abhyankar who preaches Hindutva (the ideology of India as a “Hindu nation”) and presses on Saket Ram a banned book that is probably Veer Savarkar’s influential tome of this title, the Bible of early Hindu militants; the discontented and formally deposed central Indian Maharaja whose palace contains a goddess temple-cum-arsenal (suggestive of the secret shrine in Bankimchandra Chattopadhyaya’s famous proto-nationalist novelAnanda Math, but including, here, a portrait of Savarkar and another of Adolf Hitler, for whose agenda of “ethnic cleansing” Hindu nationalists have regularly expressed admiration) and who supplies weapons to Gandhi’s would-be assassins (as the Maharaja of Gwalior allegedly equipped Nathuram Godse); and the once-prosperous Sindhi businessman Lalwani, who has lost everything in the Partition violence and seen his wife brutally slain — and who is a stand-in for the many traumatized Sindhis (including L. K. Advani) who have played a prominent role in the political rise of the Hindu Right. Such realistic strands of identity, within the fabric of Haasan’s fiction, give special meaning to the director’s own ironic subtitle for the film (echoing that of Gandhi’s 1925 autobiography): “an experiment with truth.” Other strands include a graphic meditation on the relationship between communal violence and male fears of impotence, coded as “loss of honor” through failure to protect women: fears that are horribly addressed through the violation and (often) mutilation of women of the “Other” community. Godse’s famous defense during his trial — that he and his co-conspirators “wanted to show that there were still men left among the Hindus”— is suggested by the lovemaking that follows Saket Ram’s initiation into the plot to kill the Mahatma, culminating in a drug induced hallucination in which he fantasizes his wife’s body turning into an enormous gun. Another hallucination poses the hero himself in a graphic (and according to some viewers, far too seductive) rendition of the latter-day Ayodhya agitators’ favored propaganda poster of an “angry Rama,” muscular and armed, gazing determinedly into a gathering storm.

Indeed, the third and subtlest level of narrative here is the Ramayana saga itself, both in its own basic structure and in its myriad reinterpretations, especially as a socio-political allegory. The film’s Ram, like the epic’s, is traumatized by the loss of his wife and sets out on a quest for revenge that eventually carries him across the length and breadth of India. In the film, this journey includes a second marriage, albeit half-heartedly contracted, with a spirited girl named Mythili (“the girl from Mithila,” a favorite epithet of the epic’s heroine Sita), who, like her namesake, unsuccessfully urges her husband to abstain from violence.

Instead, Saket Ram makes his fateful decision to join the plot against the Mahatma during a folk drama in which an effigy of the demon Ravana is burned: hence during the autumn festival of Dusshera which climaxes the annual Ram-lila pageant and commemorates the demon-king’s death (and which was also the date chosen for the founding of the R.S.S. in 1925, the extremist organization whose rabidly anti-Muslim ideology nurtured Godse and his cohorts). And like the epic Ram, the film’s hero battles “demons” throughout much of the story: those of his own madness and grief; the innocent (and guilty) Muslims he kills in revenge for his first wife’s death; and Gandhi, on whom he eventually focuses as the Ravana or arch-demon, the “poison tree” (in Abhyankar’s words) behind the whole “Muslim problem.” At last, he turns against the demons of hatred and violence within himself, reunites with a brother named “Bharat,” reverently accepts a pair of sandals, and achieves, through suffering, a kind of personal “Ramraj” that Gandhi himself would have endorsed: the dream of a multi-religious, harmonious India.

Despite the Chennai riots of December 6th (chillingly prophesied by the film ), that tore apart a city that had rarely known communal violence , Saket’s dream is shown to survive his death, to be reaffirmed as Amjad Khan’s widow joins the aged Mythili in mourning her husband, and as Tushar Gandhi (the Mahatma’s actual great-grandson, though admittedly not much of an actor) joins Saket Ram’s fictional grandson in the deceased archeologist’s study: a museum-cum-shrine to his obsession with and devotion to the man he once wanted to kill. The film’s final image of these younger men opening shuttered windows to let in the daylight suggests its director’s own obsessive labor to illuminate and examine, with lights and camera, several of modern India’s repressed pasts. This sequence is accompanied by the most memorable of the film's five songs (all of which are sensitively inserted into the storyline, and reflect the versatility of famed south Indian composer Ilayaraja) — an anthem strongly critical of communalism (alas, the available DVD offers no subtitles;click here to hear the song, which begins with the film's final lines of dialogue—in which Nehru and Mountbatten discuss breaking the news of Gandhi's death):

(chorus) Ram Ram, he he Ram Ram, Ram Ram asalaam Ram Ram

Where there is no longer poverty, there will be nonviolence.

Where there is happiness, there a myriad lights will shine.

Darkness will not go, light will not come, it will not bring morning…

(just saying) Ram Ram, he he Ram Ram, Ram Ram asalaam Ram RamWho knows when Judgment Day may come?

Who knows when you and I may lose our way?

All that is in your power here is to act,

And the consequences of actions no one can avoid.

O Friends, let our religion be humanity! Friends, Let it be humanity!Learn from what is past, but think of the present and future.

Those who are gone are truly gone, not even their shadows remain.

Today, O People, light the lamp of love, O People, light the lamp of love!

Ram Ram, he he Ram Ram, Ram Ram asalaam Ram Ram

Ultimately, one’s response to HEY RAM will depend on a perception of the plausibility of Saket Ram’s eleventh hour conversion from Gandhi-hater to Gandhian, which in turn hangs on a momentous surprise reunion with Amjad in the twilit lanes of Old Delhi.

Despite Shah Rukh’s inevitable hamming (and clearly, he is trying his darndest to give a subdued and serious performance), this dramatic scene—which struck some as contrived and unconvincing—worked for me, and Amjad’s wounding by a Hindu mob caused me to viscerally relive, with Saket Ram, his own wife’s suffering, thus erasing the boundary between One’s-own and the hated and feared Other. From that moment, I was entirely in the thrall of the film’s gut-wrenching vision, and indeed wept throughout its last quarter hour. Movies seldom do this to me, and so I take my hat off to the courageous and cocky Kamal Haasan.

The film boasts gorgeous cinematography and splendid sets that meticulously recreate the period, including scores of antique automobiles, and a recreation of Mohenjo Daro dug into the Tamil earth outside Chennai. The assassination scene in the garden of Birla House, though actually shot in the South Indian hill station of Ootacamund, was so exhaustively researched and convincingly recreated that the actress playing Amjad’s mother—who, in fact, had been an eyewitness to Gandhi’s slaying as a girl of twelve—was reportedly overcome with emotion, necessitating a halt in shooting. Superb performances by an all-star cast include cameos by veterans Girish Karnad and Hema Malini, and a heavily-made-up Naseeruddin Shah, who looks surprisingly convincing as the aged Mahatma.

HEY RAM is an important and must-see film, a visceral and visionary experiment in mainstream Hindi cinema.