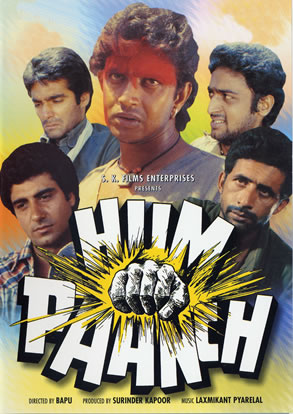

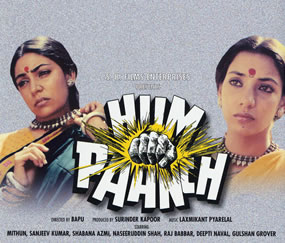

HUM PANCH

("We five"), 1980. Hindi. 153 minutes.

Directed by Bapu. Based on a story by S. R. Puttanna Kanagal. Screenplay: M. V. Ramana. Dialogues: Dr. Rahi Masoom Reza. Lyrics: Anand Bakshi. Music: Lakshmikant Pyarelal. Cinematography: Sharad Kadwe.

Half the enjoyment of this eminently enjoyable action film can only be had by those who (like most Indian viewers) are reasonably conversant with the MAHABHARATA story, and thus can savor the way in which it has been artfully retold, rearranged, and reinterpreted in a modern rural context, as an epic tale of caste and class oppression and of proletarian revolt against the hollow promises of capitalist "development." The other half comes from the gorgeous cinematography, which takes full advantage of the rugged landscape of Melkote, (in the southern state of Karnataka) and its looming Vijayanagara-period ruins.

Any sendup of the Bharata epic inevitably involves a large cast and complicated storyline. Here the five Pandava brothers are divided between three families, and Draupadi's role between two women: Sundariya and Lajiya (Shabana Azmi and Deepti Naval; appropriately, their characters' names mean "beauty" and "modesty"—two traits of the goddess Lakshmi, whom Draupadi incarnates ). Thakur Veer Pratap Singh (Amrish Puri) is a local zamindar (landlord) who rules like an iron-fisted Raja. Under the cloak of a paternalistic discourse of protection and compassion, and backed by the police and a private army of thugs, he extracts revenue from the villagers in the form of their handloomed cloth, agricultural produce, and (when he's in the mood) the sexual favors of their sisters and daughters. With his ill-gotten gain he sends his son Vijay to the big city for college and to learn the urban arts of cheating via government "rural development plans" (later, dad will go visit Vijay for an obligatory disco-decadence number in a strobe-lit club).

As the film opens, Thakur Singh—who is of course the story's Duryodhana—is secure in his kingly power, adored even by the untouchables Swaroop and Mahavir (Uday Chandra, Gulshan Grover) whose sister Sundariya (Azmi) he molests, promising to marry her. He is also tirelessly served by a third untouchable named Bhima (Mithun Chakraborty), who himself dreams of marriage to his sweetheart Lajiya (Naval). Singh is constantly flattered and advised by the film's scheming Shakuni character, Lala Nainsukh Shrivastava (Kanhaiyalal), who embodies the self-interest of low but "marginally-clean" castes (such as the Shrivastavas or Kayasthas in northeastern India) who obsequiously served the feudal order. Singh is initially opposed only by his own nephew, Arjun (Raj Babbar), who is angry over his uncle's theft of the family property and "murder" (through gambling and drink) of his father, and Suraj (Naseeruddin Shah; his name, meaning "sun," is a reference to the epic's Karna, who is sired by the sun god and becomes an ally of the Kauravas; this Karna, however, is never in doubt about his Pandava loyalties), a Bania or merchant-caste boy whose own father is in the process of being ruined by Singh. Both these angry and aware young men have left the village for higher education and hence wear modern urban clothing, in contrast to the handloomed dhotis of the other villagers.

Watching the scene with seemingly detached amusement is Krishna (Sanjeev Kumar), the Thakur's alcoholic junior brother; we learn in time, however, that he is aware of his elder sibling's crimes and is in fact counting them, waiting for their number to reach a fateful one hundred (a reference to the epic Krishna's killing of King Shishupala for the same number of sins). The Thakur himself has no fear of God, however; he invokes "tradition" and "religion" when convenient (in hypocritical speeches suggestive of those of today's Hindu nationalist politicians), lies under oath in the village temple, and neglects the festival of its large-eyed patron goddess for dalliance with a prostitute. Though the film is careful to avoid ridiculing religion (a pious local Brahman sides with the oppressed), it never resorts to the deus ex machina found in so many Bollywood screenplays. The Thakur's comeuppance, Krishna himself announces, can only come from the "awakening" of the villagers and the consciousness-raising of the three untouchables, who must join Arjun and Suraj (a Kshatriya and a Bania) to become the unstoppable fist of "we five"—an idealization of a secular, caste-liberated populace.

Epic references are numerous, creative, and carefully chosen (the clever dialogues, which joke about epic parallels even while establishing them, were penned by Dr. Reza, who would later write the screenplay for B. R. Chopra's long-running TV serial MAHABHARAT). Despite the film's blend of folktale archetypes and socialist rhetoric, the kind of oppression it depicts is still real and contemporary; Chakraborty's initial portrayal of the humiliating servility of the rural landless is disturbingly effective; his transformation into a club-wielding avenger (who will necessarily take aim at the licentious Thakur's thigh) appropriately satisfying. There is a fateful game of cards, a disrobing of a young woman named "modesty," a Gita-style sermon delivered as a song (gita), an "exile" of the five heroes (for three months in police lock-up), a dastardly attempt to burn them alive, etc. That these events don't occur in their normal epic sequence and sometimes involve unexpected characters (e.g., the "Gita" is delivered to Suraj, not Arjun, and it is the Thakur's son Vijay—and not Suraj—whose jeep tire gets stuck in the earth at a key moment) only adds to the satisfaction of knowledgeable viewers of this romance-à-clef. Appropriately too, in a film closely connected to an ancient epic, the script constantly plays, through the lips of the villainous Lala Nainsukh, on the English word "connection," which is repeated like a mantra in multiple and meaningful contexts—suggesting the connection between people through blood kinship, romantic attachment, and class solidarity, as well as the connection of religion to reactionary discourse, of rural "development" to false promises, and indeed of the English language itself to duplicity (Vijay tells his girlfriend Nishi to speak it to the Thakur, because "We Indians are easily charmed by English").

The film opens and closes with references to Narasimha, the man-lion incarnation of Vishnu who tore out the entrails of the demon tyrant Hiranyakashipu, who had ordered his subjects to worship only himself. A repetition of the Gita's promise of divine deliverance from unrighteousness (adharma) underscores the film’s climactic imagery of popular revolt—its Krishna reveals his virata rupa (universal form) to be an awakened and energized proletariat. While a pedant might object to a retooled elite epic in which the heroes are avowedly anti-elite, the MAHABHARATA has long lent itself to precisely such local recasting, and the film displays how deftly the great epic's themes of corruption, solidarity, and righteous revenge can be lifted from their ancient varna-context and re-connected to a contemporary India in which the rhetoric of democracy and universal opportunity collides with the realities of entrenched and predatory power. As Krishna sings to the five would-be brothers, "Life itself has become a battlefield."