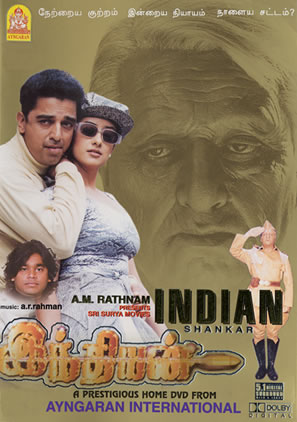

INDIAN

(1996, Tamil, 184 minutes.)

Directed by Shankar. Lyrics by Vairamuthu. Music by A. R. Rahman.

Enough happens in this big-budget, three-plus hour Madras extravaganza to leave one feeling that one has lived through an entire purana, one of those rambling anthologies of myth, folklore, and ritual praxis characteristic of medieval Hinduism. The myth, one might say, is the now larger-than-life saga of the Freedom Struggle (which forms the basis for a long emboxed narrative filmed in glorious newsreel-toned sepia), specifically its violent subbranch during the Second World War, involving the Indian National Army under "Netaji" Subhas Chandra Bose. Bose embraced the Arthasastra's realpolitik dictum that "my enemy's enemy is my friend," sided with Hitler and Hirohito, and challenged the British stereotype of the effeminate upper-caste Bengali by sporting jackboots and field marshal's uniform. He is now one of the deities in the nationalist pantheon—the militant dark twin of the non-violent, maternal Gandhi—and appears repeatedly, in the first part of the film (set in the present), as an image on the wall of government offices, where he gazes down on the appalling bureaucratic corruption that, fifty years later, his fiery struggle has spawned. He also appears as an actor during the flashback narrative, rubbing shoulders with the principal hero Senapathy (Kamal Hassan; his character's name means "general" or "leader of the army"), who has fled India—and the beautiful woman he rescued from dishonor at the hands of leering Brits—to become one of Bose's lieutenants during the INA's aborted effort to liberate India through a Japanese-backed invasion launched from Southeast Asia. Though the historical Bose died in a mysterious plane crash, the fictional Senapathy (barely) survives the INA's defeat and eventually returns from a British prison camp to wed the woman he loves in a now-independent nation.

The "folklore" element is urban and contemporary, supplied by the frame narrative of a stagnant and callous government terminally addicted to bribery. It centers around another "hero," the pragmatic Chandru (also Hassan), himself a corrupt Drivers License officer in the Transport Department in Chennai, who dreams of rising to the exalted rank of Brake Inspector (this consistently comes out as "Break Insprector" in the fractured English subtitles) so that he can marry his girlfriend Aishwarya (Manisha Koirala), an animal lover who lives amidst a menagerie of birds and beasts (including a spirited baby camel who plays, pardon the pun, a bit role). To accomplish this goal, Chandru must hand over a small fortune, and also render repeated demeaning acts of service (including the purchase of sanitary napkins and other embarrassing things), to the family of his boss, whose daughter Sapna (Urmila Matondkar) also has her eye on him. Despite the surrealism of much of the surroundings (Chandru holds court and dispenses favors from the driver’s seat of a rusted Plymouth convertible), there is manic inventiveness in the constant, humorous allusions to contemporary culture (at one point the heroine is poetically described as "a computer designed by Brahma") as well as spot-on accuracy in the portrayal (through both comic and tragic episodes) of the kind of frustration and callous mistreatment that average Indians endure on a daily basis in their "license Raj."

This feeds into yet another subplot: a feel-good revenge narrative of a mysterious serial killer of bribe-taking officials, who leaves notes signed only "Indian," and who is, in fact, a dignified rural septuagenarian (Hassan yet again)—indeed, the now-aged Freedom Fighter Senapathy. Who is also Chandru’s estranged father. Oh yes, he's also an exponent of a nearly-dead but way cool Keralan martial art involving deadly manipulation of the vital breath (prana), which he uses to immobilize his victims prior to disemboweling them with a curved dagger he wears concealed in his belt. Like Michael Douglas in FALLING DOWN, the dignified but spry Senapathy, as the average guy pushed too far by a corrupt system, mobilizes the rage of the audience, which can relish his mayhem even as it enjoys the high-tech ingenuity of the dogged police inspector who seeks to bring him to.....er, justice. And of course, viewers may anticipate that at some point idealistic, veshti-wrapped, bribery-hating father is bound to encounter cynical, polyester-clad, bribe-taking son....

The third element is the ritually de rigeur music and dance sequences, which continue to push the envelope on exotic spectacle and digital effects, a realm in which Madras filmmakers regularly trump those of Bollywood in sheer visual inventiveness; these numbers are only barely linked to the plot and seem meant to be enjoyed purely for their own sake. Another toe-tapping A. R. Rahman score (accompanied here by lyrics in his mellifluous mother tongue) backs up an array of eye-popping sequences, including a supposed rehearsal for a college "fashion show" that quickly morphs into a disco-driven phantasmagoria of surreal costumes and multi-tiered sets. There's the obligatory (and obligatorily unexplained) overseas interlude, in which Chandru and animal-loving Aishwarya frolic in Australia amid herds of bouncing kangaroos, get formal on the steps of the Sydney Opera House, and make love in 18th century costume on a moonlit Tall Ship. There's a flag-waving salute to Independence in 1947, all aglitter with auspicious oil lamps and bursting fireworks. And there's a video-game-like fantasy in which Chandru, as a magician-hero, breaks into an evil king's palace to woo his beloved; this song matches coyly erotic lyrics to imagistic overload as the hero transforms digitally into a flame, lion, stallion, throne, bird of prey, etc. etc.

Transformation, indeed, seems to be the main "message" of the film: the transformation of India from idealistic republic to corruption-driven consumer Raj, of heroes to villains and vice-versa, of a field of rice into a digitalized map of the Motherland (cf. the famous sequence in MOTHER INDIA), and (perhaps above all) of the versatile Kamal Hassan, a Southern hero-with-a-thousand-faces (he once played five characters in a single film) into the literal embodiment of all of this: the corporeal summation, celebration, and condemnation of who we are, were, and might be.