JAGTE RAHO (“Stay awake!”)

1956, Hindi, 139 minutes

Directed by Sombhu Mitra and Amit Maitra

Produced by Raj Kapoor

Based on the Bengali play and film Aykdin Ratrey ("One night"), produced by IPTA and directed by Sombhu Mitra; Story and screenplay: Sombhu Mitra, Amit Maitra; Dialogues: K. A. Abbas; Music: Salil Chaudhary; Lyrics: Shailendra, Prem Dawan; Cinematography: Radhu Karmakar

Had Foucault, Ionesco, and Rossellini been genetically joined and incarnated in India, they might have collectively imagined something like this mordantly absurdist satire, which must rank among the masterpieces of 1950s popular cinema. But since they weren’t, the full credit goes to R.K. Studios and its helmsman, Raj Kapoor, here teaming up with Bengali theatre greats Shambhu Mitra and Salil Chaudhary. Kapoor appears at the height of his powers as actor, storyteller, and risk-taking producer. His Chaplinesque “Raju” character makes his third appearance, wearing his trademark ratty jacket but now trading his skimpy pantaloons for an equally skimpy dhoti, to portray a terrified villager who has just arrived, in the dead of night, in the Big City (unidentified and generic, though Calcutta street scenes appear during the opening credits), and who is in search of the most basic of all amenities: a sip of water. He quickly runs afoul of the watchmen who patrol the city’s streets (periodically crying “Jagte raho!” or “Stay awake!” to assure one another, and the municipal committees that pay them, that they are on the job). But he is befriended by a stray dog (in a scene that alludes to the similar one in AWARA) who leads him to a leaking tap inside a massive and gated middle-class apartment complex.

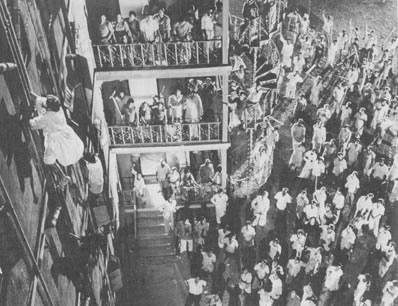

The chaos that results from the presence of this alleged “thief” is virtually indescribable, but marvelous to behold. It is also, in its own way, utterly plausible. Darting from flat to flat in his efforts to escape the mob, Raju witnesses and exposes a range of vices that masquerade as bourgeois respectability (and that, indeed, make it possible), and mercilessly reveals how, in the status and security-obsessed world of the middle classes, only a thin line may separate domestic civility from petty crime, tawdry scandal, idiotic vendetta, and indeed mindless mob vigilantism. More trenchant, even prophetic, is the film’s sensitivity to the range of middle-classness and its political ramifications: in the panic that follows the rumor of a thief in their midst, the wealthier residents rapidly organize (with financial incentives) the poorer ones into quasi-military squadrons of armed (if ineffective) goons to hound out the offending subaltern Other.

In a further Chaplinesque touch, Raju barely speaks throughout most of the film, conveying his emotions through slapstick and pantomime, but abruptly offers one fervent denunciatory speech (a la The Great Dictator) at its climax. In this moment, as well as in the reverent (censor-pleasing?) montage of national heroes that briefly follows, the plot seems to momentarily veer from its cynical course. The coexistence of patriotic schmaltz with trenchant social critique is of course characteristic of Kapoor’s films, as is the suggestion, in the apotheosis-like finale, that the vision of a buxom goddess in a blouseless sari (played by Nargis, naturally), accompanied by a soaring hymn to Krishna, (Jaago Mohan pyaare, “Wake, O beloved Enchanter”) might suffice to lift this dark Dystopia into a bright New Day. The awakened viewer gets to choose between lingering skepticism, and surrender to enchantment—or go away savoring both.

Other songs are sparingly yet brilliantly used to advance the plot. The opening Kabir-like bhajan (Zindagi khwab hai, “This life is a dream”), sung by a drunken bon vivant, establishes and celebrates the cinematic sur-reality we are entering even as it prefigures the heavy ironies that it will shortly reveal. The ludicrous “Maine jo lee angdai” (“When I stretched my limbs”) is a sendup of raucous cinema lovesongs with nonsense refrains, and is played as an HMV phonograph record by a debauched husband who wants his own wife to mimic the erotic dancing of film actresses (Why not?, one wonders. The directors seem of two minds about it too. While the “real” bourgeois spouse hides in terrified respectability in the bedroom, Raju, clutching a skirt, is hallucinated into her dancing double by the husband—and the same actress, of course, appears in this role as well, looking perfectly fetching in the “sinful” adornment of atawaayaf or courtesan.)

The vast yet claustrophobic set, designed by K. Damodar, is another of the film’s triumphs, and likewise strikes a prophetic note; though only a few housing complexes on this scale existed in 1956, they are ubiquitous now in the Indian metropolis. The locked gates, receding hallways, scurrying residents, and three-digit flat numbers that are mindlessly reeled off add to the inescapable message that this comfortable upscale development — the sort of housing to which many Indians aspire — is not only a warren of iniquities and sorrows concealed behind every nameplated door, but also a vast, self-policing prison that traps its denizens in their prejudices and fears.

[Despite its cautionary opening message—“The following film has been restored from vintage source for the nostalgic appeal hence possibly compromising in video and audio quality.”—the Yashraj Films DVD of JAGTE RAHO offers an excellent quality print, superior to those marketed by the same company for AWARA and SHRI 420. The subtitles are adequate and thankfully appear for songs as well.]