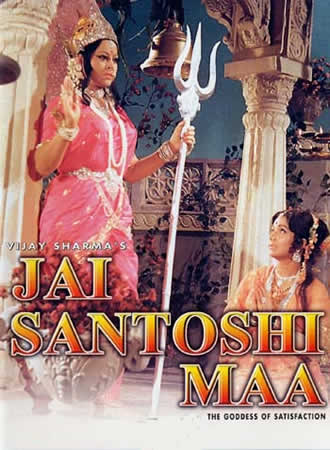

JAI SANTOSHI MAA

“Hail Santoshi Ma!”

1975, Hindi, 138 minutes

Directed by Vijay Sharma

Produced by Satram Rohra

Screenplay: R. Priyadarshi; Music: C. Arjun; Lyrics: Pradeep; Cinematogarphy: Sudhendu Roy; Art Direction: Hirabhai Patel

This low-budget film with unknown actors unexpectedly emerged as one of the highest-grossing releases of 1975—sharing the spotlight with the likes of SHOLAY and DEEWAR. This bewildered critics and intrigued scholars (resulting in a modest literature on the film as a religio-cultural phenomenon), but made perfect sense to millions of Indian women, who loved its folksy story about a new “Goddess of Satisfaction,” easily accessible through a simple ritual (which the film also demonstrates). A classic example of the “mythological” genre—the original narrative genre of Indian-made films—and one of the most popular such films ever made, it gave a new (and characteristically Indian inflection) to the American pop-critical term “cult film,” for viewers often turned cinemas into temporary temples, leaving their footwear at the door, pelting the screen with flowers and coins, and bowing reverently whenever the goddess herself appeared (which she frequently did, always accompanied by a clash of cymbals). Despite tacky sets and the crudest of special effects, the film features a well-crafted script, with witty dialogs that abound in cultural references, and its devotional songs are extremely catchy (for years they could be heard blaring from temple loudspeakers all over India). Overall, the film has a charmingly playful quality, especially in its (often comically unflattering) portrayal of divine personalities, which is characteristic of folk Hinduism.

The screenplay is based on a vrat katha: a folktale (katha) meant for recitation during the performance of a ritual fast (vrat) honoring a particular deity and undertaken in order to achieve a stated goal. The Santoshi Ma vrat seems to have become popular in north India during the 1960s, spreading among lower middle-class women by word of mouth and through an inexpensive “how-to” pamphlet and religious poster of the goddess. However, the printed story is very sketchy and the film greatly embellishes it, adding a second narrative to its tale of a long-suffering housewife who gets relief through worshiping Santoshi Ma.

The film opens in dev lok or “the world of the gods,” a Hindu heaven located above the clouds, where we witness the (unplanned) “birth” of Santoshi Ma as the daughter of Ganesha, the elephant headed god of good beginnings, and his two wives Riddhi and Siddhi (“prosperity” and “success”). A key role is played by the immortal sage Narada, a devotee of Vishnu, and a cosmic busybody who regularly intervenes to advance the film’s two parallel plots, which concern both human beings and gods. We soon meet the maiden Satyavati (Kanan Kaushal), Santoshi Ma’s greatest earthly devotee, leading a group of women in anarti (song and ceremony of worship) to the goddess. This first song, Main to arti utaru, “I perform Mother Santoshi’s arti,” exemplifies through its camerawork the experience of darshan—of “seeing” and being seen by a deity in the reciprocal act of “visual communion” that is central to Hindu worship.

Through the Mother’s grace, Satyavati soon meets, falls in love with, and manages to marry the handsome lad Birju (Ashish Kumar), youngest of seven brothers in a prosperous farm family, an artistic flute-playing type who can also render a zippy bhajanon request (Apni Santoshi Maa, “Our Mother Santoshi”). Alas, with the boy come the in-laws, and two of Birju’s six sisters-in-law, Durga and Maya (named for powerful goddesses) are jealous shrews who have it in for him and Satyavati from the beginning. To make matters worse, Narada (in a delightful scene back in heaven) stirs up the jealousy of three senior goddesses, Lakshmi, Parvati, and Brahmani (a.k.a. Sarasvati)—the wives of the so-called “Hindu trinity” of Vishnu, Shiva, and Brahma—against the “upstart” goddess Santoshi Ma. They decide to expose her worship as useless by making life miserable for her chief devotee.

After a fight with his relatives, Birju leaves home to seek his fortune, narrowly escaping a watery grave (planned for him by the goddesses) through his wife’s devotion to Santoshi Ma. Nevertheless, the divine ladies convince his family that he is indeed dead, adding the stigma of widowhood to Satyavati’s other woes. Her sisters-in-law treat her like a slave, beat and starve her, and a local rogue attempts to rape her; Santoshi Ma (played as an adult by Anita Guha), taking a human form, rescues her several times. Eventually Satyavati is driven to attempt suicide, but is stopped by Narada, who tells her about the sixteen-Fridays fast in honor of Santoshi Ma, which can grant any wish. Satyavati completes it with great difficulty and more divine assistance, and just in the nick of time: for the now-prosperous Birju, stricken with amnesia by the angry goddesses and living in a distant place, has fallen in love with a rich merchant’s daughter. Through Santoshi Ma’s grace, he gets his memory back and returns home laden with wealth. When he discovers the awful treatment given to his wife, he builds a palatial home for the two of them, complete with an in-house temple to the Mother. Satyavati plans a grand ceremony of udyapan or “completion” (of her vrat ritual) and invites her in-laws. But the nasty celestials and sadistic sisters-in-law make a last-ditch effort to ruin her by squeezing lime juice into one of the dishes (key point here: the rules of Santoshi Ma’s fast forbid eating, or serving, any sour food). All hell breaks loose—civil war between goddesses!—before peace is finally restored, on earth as it is in heaven, and a new deity is triumphantly welcomed to the pantheon.

In an era dominated by violent masala action films aimed primarily at urban male audiences, JAI SANTOSHI MAA spoke to rural and female audiences, invoking a storytelling style dear to them and conveying a message of vindication and ultimate triumph for the sincerely devoted (and upwardly-mobile). Above all, it concerns the life experience that is typically the most traumatic for an Indian woman: that of being wrenched from her mayka or maternal home and forced to adjust to a new household in which she is often treated as an outsider who must be tested and disciplined, sometimes harshly, before she can be integrated into the family. Satyavati’s relationship with Santoshi Ma enables her to endure the sufferings inflicted on her by her sisters-in-law and to triumph over them, but it also accomplishes more. It insures that Satyavati’s life consistently departs from the script that patriarchal society writes for a girl of her status: she marries a man of her own choosing, enjoys a companionate relationship (and independent travel) with her husband, and ultimately acquires a prosperous home of her own, beyond her in-laws’ reach. While appearing to adhere to the code of a conservative extended family (the systemic abuses of which are dramatically highlighted), Satyavati nevertheless quietly achieves goals, shared by many women, that subvert this code.

This oblique assertiveness has a class dimension as well. The three goddesses are seen to be “established” both religiously and materially: they preside over plush celestial homes and expect expensive offerings. Santoshi Ma, who is happy with offerings ofgur-chana (raw sugar and chickpeas—snack foods of the poor) and is in fact associated with “little,” less-educated, and less-advantaged people, is in their view a newcomer threatening to usurp their status. Yet in the end they must concede defeat and bestow their (reluctant?) blessing on the nouvelle arrivée. The socio-domestic aspect of the film (goddesses as senior in-laws, oppressing a young bahu or new bride) thus parallels its socio-economic aspect (goddesses as established bourgeois matrons, looking scornfully at the aspirations of poorer women)

.

Satyavati’s relationship to Santoshi Ma, established through the parallel story of the goddesses, suggests that there is more agency involved here than at first appears to be the case—though it is the diffused, depersonalized agency favored in Hindu narrative (as in Santoshi Ma’s own birth story). Satyavati’s successful integration into Birju’s family, indeed her emergence as its most prosperous female member, parallels Santoshi Ma’s acceptance in her divine clan and revelation as its most potent shakti. In both cases this happens without the intervention, so standard in Hindi cinema, of a male hero.

Through its visual treatment of the reciprocal gaze of darshan and its use of parallel narratives, the film also suggests that Satyavati and Santoshi Ma are, in fact, one—a truth finally declared, at film’s end, by Birju’s wise and compassionate elder brother Daya Ram. As in the ideology of tantric ritual (or the conventions of “superhero” narrative in the West), the “mild-mannered” and submissive Satyavati merges, through devotion and sheer endurance, with her ideal and alter-ego, the cosmic superpower Santoshi Ma. There is a further theological argument that the film visually offers: not only is Santoshi Ma available to all women through her vrat ritual, she is, in fact, all women. Appearing as a little girl at the film’s beginning, as a self-confident young woman in her manifestations throughout most of the story, and as a grandmotherly crone on the final Friday of Satyavati’s fast, Santoshi Ma makes herself available to viewers as an embodiment of the female life cycle, and conveys the quietly mobilizing message that it is reasonable for every woman to expect, within that cycle, her own “satisfaction” in the form of love, comfort, and respect.

Resources:

Das, Veena. 1980. “The Mythological Film and Its Framework of Meaning: An Analysis of Jai Santoshi Ma.” India International Centre Quarterly 8:1, 43-56. (A groundbreaking article by one of India’s leading sociologists.)

Eck, Diana. 1981. Darsan: Seeing the Divine Image in India. Chambersburg, PA: Anima Books.

Erndl, Kathleen M. 1993. Victory to the Mother: The Hindu Goddess of Northwest India in Myth, Ritual, and Symbol. New York: Oxford University Press. (includes a section on Santoshi Ma)

Kurtz, Stanley N. 1992. All the Mothers Are One: Hindu India and the Cultural Reshaping of Psychoanalysis. New York: Columbia University Press. (An elaborate psychoanalytic analysis of Hindu goddesses that takes the Santoshi Ma cult as a starting point; includes much discussion of the film.)

[The Worldwide Entertainment Group (WEG) DVD of JAI SANTOSHI MAA is of decent, though not superior, quality and includes subtitles for song lyrics.]