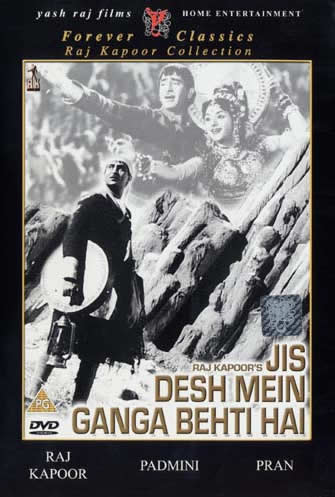

JIS DESH MEIN GANGA BEHTI HAI

(“The land where the Ganges flows”) 1960, Hindi, 174 minutes

Produced by Raj Kapoor

Directed by Radhu Karmakar

Story, screenplay and dialogue: Arjun Dev Rashk; Lyrics: Shailendra, Hasrat Jaipuri; Music: Shankar, Jaikishan; Choreography: Hiralal; Cinematography: Tara Dutt; Art direction: M. R. Achrekar

This lavish dacoit fantasy—as visually sumptuous as it is ideologically ingenuous—might be classified as “high middle” Raj Kapoor, for it seems to provide a bridge (in this case, perhaps a “Laxman jhoola”—the suspension bridge over the Ganges at Rishikesh that appears in the opening sequence) between early B/W triumphs like AWARA and SHRI 420 and later Kapoor-directed crowd-pleasers like BOBBY and RAM TERI GANGA MAILI. In the great RK Studios tradition, it combines Hindu mythic and folkloric themes with a discourse of “national integration” and a shamelessly voyeuristic preoccupation with female anatomy. Kapoor himself stars in one of the last incarnations of his trademark Chaplinesque “Raju”—the Hindustani everyman, who here takes on the identity of a bhat or “bard.” Though the term usually refers to a caste of genealogists and storytellers, it is invoked here in the service of a typically complex and composite Raju persona positioned between tradition and modernity: a pious “son of Mother Ganges” who wears a sacred thread and the tied-on tunic known as chaubandi (favored by Brahman pandits) incongruously combined with military-style shorts and puttees, and who carries a fork, toothbrush, and hurricane lantern (“modern” amenities, all), along with a dafli (a large tambourine), in his curious gear—he thus appears as something of a hybrid of peasant-pilgrim, sadhu, and sepoy, and becomes a “social worker” of sorts as the film unfolds. Raju’s religiosity is focused on vague invocations of “Lord Shiva’s blessings” and on the river Ganga as life-giving “mother” to all Indians. His political philosophy combines Gandhian do-unto-others nonviolence with Nehruvian themes of nation-building and cultural integration. Kapoor’s longtime costar (and reputed mistress) Nargis being out of his life by this point, Raju’s nymphet-du-jour is the buxom and vivacious Padmini, here portraying Kammo, the headstrong daughter of a brigand chieftain of the ravines of Bundelkhand in north-central India.

Following the credits and a series of shots that follow the “descent of the Ganges” from the high Himalayas to the plains, Raju’s establishing song (Mera naam Raju, “My name is Raju”) features him on a raft drifting past famous pilgrimage centers like Rishikesh, Hardwar, Allahabad and Banaras, playing hisdafli and singing of his simple faith in the river, love, and music. This cuts abruptly to a nighttime sequence of a violent dacoit raid on an apparently model village (the Hindi slogan “Grow more grain” appears above its neat gateway), involving murder, looting, cattle-rustling, and arson, and culminating in a chase by truckloads of police, in the course of which the dacoit sardar or chief is shot in the leg. Hiding in the woods, he encounters the wandering Raju, who binds his wound and nurtures him with Ganges water and his own humble food. Taken to the brigand camp, Raju is denounced as a police informer by the suspicious and cruel Raka (Pran), an ambitious young gang member, but is shielded by the sardar, who credits Raju with saving his life.

The chief’s daughter Kammo quickly takes a shine to the strange simpleton. This blossoms into full-blown passion which she declares in the abandoned song and dance Kyaa huaa (“What has happened?”) and still more in the wet and wildly erotic Ho maine pyaar kiya (“O, I’ve fallen in love”), performed to the accompaniment of heated panting and an aquatic ballet that recalls the “By a waterfall” sequence in Busby Berkeley’s FOOTLIGHT PARADE (1933). Raju’s own glorification of traditional Indian values of honesty and hospitality is articulated in his many speeches to the bandits, as well as in his performance of the title song.

“Where truth lives on the lips and honesty in the heart,

Where a guest is held to be dearer than one’s own life,

We are dwellers in that land,

That land where the Ganga flows!”

Though initially chary of the bandits’ rough ways and bloodthirsty lifestyle, Raju is briefly converted by Kammo’s Robin Hood-like espousal of their ideology (“We make the rich and poor more equal”—which leads Raju to declare, “Oh, you are socialists!,” comically mispronouncing the English word). But when he participates in an actual raid on a village wedding, he is horrified by the bloodshed and denounces the dacoits to the local police—then, incongruously, warns the bandits of this so that they too may escape further harm, thus exposing himself to their wrath. Raju’s growing efforts to “convert” the thieves to a nonviolent way of life—which explicitly involves “joining the Nation” whose authority is symbolized by the hated police—creates fissures in their ranks, with Kammo, the maternal Bhauji (Lalita Pawar), and a few of the men taking Raju’s side, and the rest joining with the cruel Raka in overthrowing the now-weakened sardar. Through a series of plot twists, the stage is set for a climactic confrontation between the massed forces of the rural police and the now-divided dacoits, with Raju as mediator. Walking Moses-like at the head of a caravan of disarmed brigand families, he sings Aa, ab laut chalen—“Now come, let’s return” (to society)—even as rifle-bearing troops surround them.

Viewers may likewise feel divided by this point. On the one hand, the film voyeuristically romanticizes dacoit society—visually portrayed through a colorful mélange of rustic and tribal styles—as a premodern economy of earthy, forthright people, whose women speak their minds (and desires) and whose feet are always ready to break into uninhibited dance. On the other hand, it problematizes these same people as criminal predators living in constant fear of the hangman’s noose, and in need of moral reformation and integration into “the arms of the Nation”—presumably through trading their rifles for plowshares and “settling down” to become the sort of villagers who were their erstwhile victims. One is reminded that the Indian state has largely continued the British colonial policy of monitoring and (whenever possible) “settling” tribal and pastoral peoples, who were often classified in colonial times as “Criminal Castes and Tribes” simply because they eluded census takers and tax collectors and participated in the “informal” economy that lay beyond the urban capitalist infrastructure. Raju’s intervention in dacoit society is flavored by both the traditional process of “Sanskritization,” wherein lower-class groups are encouraged to raise their social status by adopting the customs of high-caste Hindus (and his interactions with the bandits implicitly recall the popular folktale of the ancient poet Valmiki’s conversion from bloodthirsty highwayman to saint through the exhortation of a group of Brahman sages he was preparing to rob), and the new ideological agendas of Gandhian non-violence and Nehruvian progressivism. This recipe was clearly supposed to work back in 1960, when middle class viewers still regarded the State as essentially benevolent and paternalistic. But after decades of worsening bureaucratic and high-level corruption, and widely-contested social engineering schemes—including massive displacements of tribal peoples by dams and other development projects—the final triumphalist scenes of repentant dacoit-folk resigned to “resettlement” being rounded up and loaded into open trucks by phalanxes of bayonet-toting soldiers appears more than a little unsettling.

Despite this, the film proffers visual delights throughout, including both impressive location work (as in the scene when Kammo pursues the fleeing Raju through the jagged ravines of the Narmada River near Jabalpur, and the final dramatic confrontation in a stark valley) and impressive soundstage sets, such as the ruined fortress that hosts the dacoit hideout. The camerawork is excellent, the choreography impressive, and the strong score of nine songs by Kapoor’s stalwart team of Shailendra, Jaipuri, and Shankar-Jaikishan definitely up to scratch.

[The Yashraj Films’ DVD of JIS DESH MEIN features a generally excellent quality print, and includes English subtitles both for songs and dialog.]