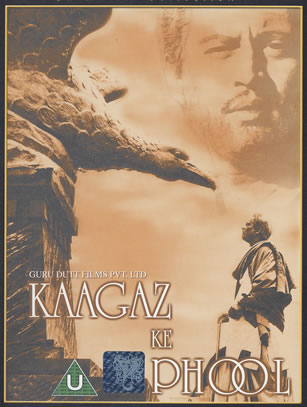

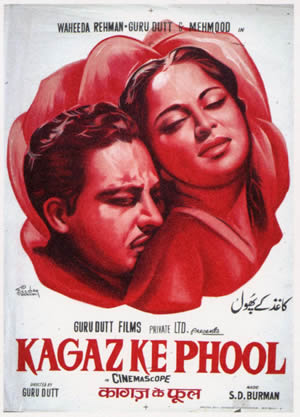

KAAGAZ KE PHOOL ("Paper Flowers," Hindi, 1959)

B&W, 153 minutes. Directed by Guru Dutt.

Cinematography by V. K. Murthy. Screenplay by Abrar Alvi. Lyrics by Kaifi Azmi. Music by S. D. Burman.

Guru Dutt's melancholic masterpiece, and India’s first cinemascope film, weds visionary and often breathtaking cinematography to an archetypal but anachronistic (and heavily morose) storyline. The feeling of having seen the latter one too many times (in DEVDAS, PYAASA, etc.) may have contributed to audiences rejecting this rendering, a rejection that is said to have contributed significantly to the director's own descent into depression, culminating in his suicide in 1964. Seen from hindsight and read against the (now looming) legend of Guru Dutt, the film thus intertwines three narratives: two that we know but never see (the tragic and twice-filmed DEVDAS story—of a melancholic hero who drinks himself to death—which Dutt's hero is filming yet once again; and Dutt's own larger-than-life tragedy, prophesied by this film) with the one presented to us: the tale of the self-destructive genius cinephile and director, Suresh Singh (Guru Dutt), and of his discovery, the extraordinary beauty Shanti (Guru Dutt's discovery, Waheeda Rehman).

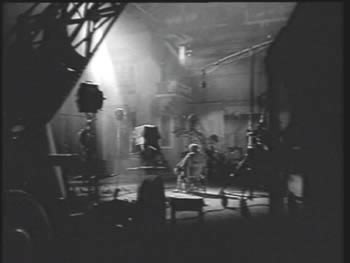

Unfolding in flashback, as the alcoholic and prematurely-aged Suresh sits in an empty soundstage of Ajanta Studios, where he once directed hit films, singing Dekhi zamaane ki yaari ("I have seen the age of glory"), the story opens with a series of gloriousy operatic tableaux depicting the zenith of Suresh's career, when cheering crowds acclaimed his movies (this sequence recalls the climactic moments of PYAASA when the presumed-dead poet Vijay enters the theatre where his work is being "posthumously" celebrated). Here, the Ajanta emblem, dominating both the studio lot and the lobby of its flagship theatre—of a giant Garuda-eagle, atop which a divine figure sounds his conch-shell trumpet—seems to evoke the cinema's magical ability to give wings to the imagination and cause the world to reverberate with song. Yet this joyous heraldic image will acquire a cruel, almost fascistic overtone, as its stone face gazes unpityingly on Suresh's precipitous fall, and in a crane shot we see his wasted form framed between the sandaled feet of its rider, which resemble those of a haughty Roman emperor. Sic transit gloria—and the transit here is mercilessly swift.

The storyline is simple, though its development is at times uneven. The brilliant and lionized Suresh has an abiding sorrow: his separation from his daughter Pammi (Baby Naaz). She was taken away from him by his estranged wife, the aristocratic Bina (Veena), who (together with her equally snobbish and ludicrously Anglophile parents) despises the world of cinema and its inhabitants—this portrait is not as extreme as it may appear, since a disdain, real or pretended, for Indian films and their makers is often effected by the elite. Attempting to see Pammi in her boarding school in Dehra Dun, Suresh encounters Shanti, who works there, offering her his overcoat during a downpour. Later, she comes to Bombay seeking employment and returns the coat, leading to her accidental screentest and discovery. Her radiant beauty as the heroine Paro, embodying the simplicity of a "pure Indian woman," makes Suresh's DEVDAS a smash hit, but the budding mutual love between the pair—expressed in the poignant song Waqt ne kiyaa (“What has time done?,” sung by Guru Dutt's wife Geeta), which is heard but not mouthed as the two principals gaze at one another on an empty soundstage—is stifled by Pammi's doomed effort to reunite her parents by removing Shanti from the picture—and from Suresh’s films.

Without Shanti's companionship and her faith in him, Suresh succumbs to a depression fueled by a combination of alcoholism and pride, the latter preventing him from accepting numerous offers of help, including several from Shanti herself. That Suresh is so clearly his own worst enemy makes it difficult for viewers to sympathize with him—an outcome that Guru Dutt may doggedly have intended. After Suresh has half-heartedly directed a string of flops, his studio bosses finally cut him loose. His subsequent downhill slide is broken only by the occasional walk-on antics of Johnny Walker (who plays Rakesh, the horse-racing and womanizing brother of Suresh's estranged wife; this vidushaka role, however, is not well integrated into the story) and some wrenching melodramatic coincidences—as when Pammi drives past her father living in the derelict garage of his former chauffeur, or when Shanti recognizes him among the scruffy extras brought in for a "mythological" in which she is starring—itself evidently another sendup of the much-filmed legend of the poet-saint Mirabai, who spent her life pining for her absent "bridegroom," Lord Krishna.

In the end, though one may wish that Suresh had gotten some decent therapy ("Prozac," my wife announced, "could have done wonders for him"), it is the cinephilic images of his tormented memory that linger before the mind's eye: the transfiguring spotlights of deserted soundstages, the misty make-believe distance of sets, the transcendent and unapproachable beauty of Shanti, wrapped in a star-aura we watch being created yet succumb to all the same. Indeed (and again in hindsight) the film constitutes a twilight-elegy for Bombay's director-dominated studio era, and prophesies the dawning one in which the shots will be called by megastars. Beyond this, it offers a still higher allegory: of cinematic artifice as the emblem of this world of "paper flowers" and broken hearts, the subject of mournful Urdu ghazals and of renunciant sant songs—such as that which opens and closes the film. Flaws and all, KAAGAZ KE PHOOL deserves to rank—with Fellini's 81/2—among the all-time great films about filmmaking and life.

[Corey Creekmur adds, on possible cinematic influences on Guru Dutt:

“In addition to its Indian allusions, the film seems to explicitly evoke the storyline of WHAT PRICE HOLLYWOOD? (1932), remade more famously as A STAR IS BORN (1937) and as a hit musical in 1954--the latter, with Judy Garland and James Mason, is Dutt's most plausible inspiration. All chronicle the rise of a female star and the fall of a male mentor (through alcoholism, among other things): all present a male "hero" who is somewhat unsympathetic and, against Hollywood expectations, cannot be cured. I suspect Vincente Minnelli's THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL (1952), another Hollywood expose and an even more direct commentary on the end of the studio system, starring Kirk Douglas and Lana Turner, might have informed Dutt too: like Kaagaz, it's told in flashback.”]

For additional reading: Nasreen Munni Kabir, Guru Dutt: a life in cinema (Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). This sensitive tribute to Guru Dutt contains a fascinating chapter on Kaagaz ke phool, including the reminiscences of several close associates of the director.