KALA PANI

(“Life Sentence”)

1958, Hindi, approx. 164 minutes

Directed by Raj Khosla

Produced by Navketan

Story: Anand Pal; Screenplay: G. R. Kamat; Dialogues: Bhappi Sonie; Lyrics: Majrooh Sultanpuri; Music: S. D. Burman; Cinematography: V. Ratra.

Despite an unevenly contrived plot and some sketchy acting by Dev Anand—whose thin character here risks being overwhelmed by the cresting wave of his trademark pomaded forelock —this crime drama offers enough visual and musical pleasures to make one wish that it were available in a better quality DVD (see below). As the film opens, the inevitable Mother in Distress rushes toward the camera through a long series of double doors—a motif of desperate motion and the opening of barriers (to truth, freedom, etc.) that will be repeated several times. She is distraught because her son Karan (Anand) finally “knows the truth” about his father Shankarlal; namely, that he is not (as Karan has been told) dead, but rather is in prison in Hyderabad, fifteen years into a life sentence (euphemistically known askala pani or “black water,” from the colonial-era practice of transporting such convicts to the remote Andaman Islands) for the murder of a tawayaf or courtesan named Mala. Shankarlal’s guilt is assumed by Karan’s mother and uncle, but Karan is immediately convinced of the opposite (for no apparent reason, except that it is a question of his revered Father’s character), and heads to Hyderabad to uncover the truth and set Dad free.

His quest leads him to a newspaper office where he encounters the lovely and spirited reporter Asha (Madhubala), who also happens to own the guesthouse in which he lodges. Three bumbling roommates, one of whom is an aspiring Urdu poet, provide comic relief and assist in several impersonations aimed at uncovering the real culprits—a wealthy drug-addicted Diwan (aristocrat) and his corrupt attorney (Kishore Sahu).

Though the plot is too clunky to offer much suspense or surprise—an idealistic lad like Karan is not going to turn out to be wrong in his convictions—it compensates with an oddly effective subplot involving a key witness, another tawayaf named Kishori (Nalini Jaywant), who has grown rich through blackmailing the villainous courtier. This permits Karan to disguise himself as a Muslim dandy and aspiring shayar (poet) and to enter the fabled world of the Hyderabadi demimonde, where music, poetry, and prostitution (of a refined sort) reign supreme. Here the director deploys inventive camerawork that exploits lattices, veils, and balustrades to maximum voyeuristic effect.

There is some real charm in Anand’s debonair impersonation, especially in the song Hum bekhudi mein tumko pukare (“Distracted with love, I call to you,” sung by Mohammed Rafi), but Jaywant is even more effective, first as a seductive coquette (in the song Nazar laagi raja tore bangle par, “I lost my heart in your abode, sir”), and later in bringing dignity and poignancy to the clichéd role of the public woman who outwardly sparkles but inwardly suffers, yearning for true love and the respectability of marriage (most effectively conveyed through the song Kya kahiye hamen kyaa yaad aaya “What can I say of my memories?”; both songs performed by Asha Bhosle).

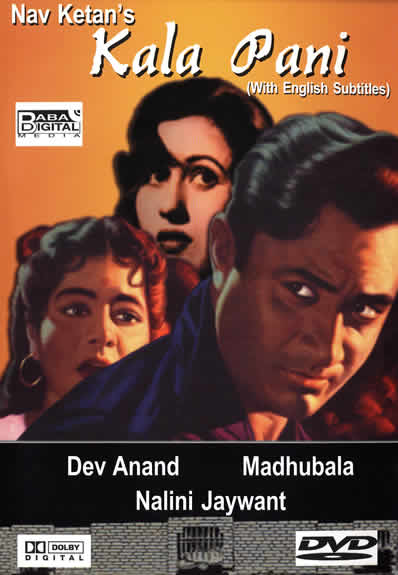

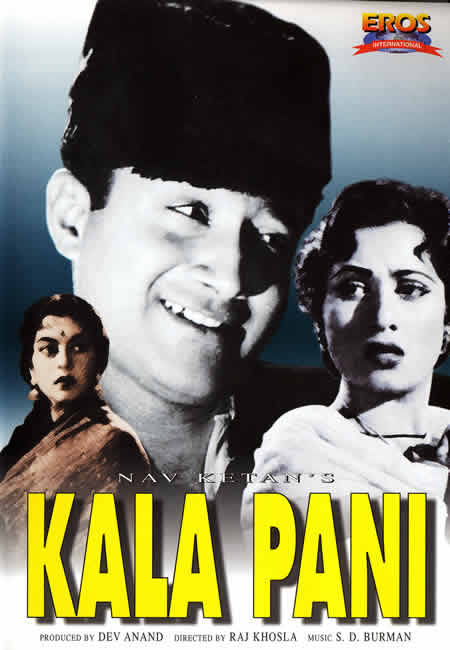

[At least two DVDs of KALA PANI are on the market. The Baba Digital version is of even poorer quality than is usual with this company. Although image quality is tolerable, there are numerous jerky transitions suggesting that the film was torn and carelessly spliced, leaving out segments. The Eros International version seems to have been made from a superior print and is more complete, however the soundtrack is notably and annoyingly out of synch with the visuals, and this continues throughout the film. Subtitles are adequate in both, but are not provided for songs. Though no masterpiece, this film deserves better.]