KASHMIR KI KALI

(“bud of Kashmir”)

1964, Hindi, 168 minutes

Produced and directed by Shakti Samanta

Story and screenplay: Ranjan Bose; dialog: Ramesh Pant; lyrics: S. H. Bihari; music: O. P. Nayyar; art direction: Shanti Das; choreography: Surya Kumar; director of photography: V. N. Reddy

This visually sumptuous and robustly entertaining film shows off the talents of Shammi Kapoor (born Shamsherraj Kapoor in 1931), whose screen persona, developed through such hit films as TUMSA NAHIN DEKHA (1957) and JUNGLEE (1961), combined the hipster gyrations of Western teen idols like Elvis Presley and Cliff Richard, the spasmodic slapstick of Jerry Lewis, and the romantic histrionics of his elder brother Raj Kapoor (only more so). Here he stars in another variation on a narrative chestnut of which his brother (and many others) was fond: rich urban boy goes to the countryside (often the Himalayas) and falls in love with poor local girl who embodies the simplicity and sensuality of “nature,” as well as the coded ethnicity of the peripheral and minority-dominated “provinces” (e.g., in such films as BARSAAT, SATYAM SHIVAM SUNDARAM, and RAM TERI GANGA MAILI; for a darker recent variant, see DIL SE). Hence the couple’s love match offers a pairing that appeals to both male notions of the harmony of culture-nature (the former being masculine and dominant) and the politico-cultural program of “national integration” (since the boy simultaneously embodies urbanity, modern technology, and a centralized Congress-style national vision).

There is a vestigial nod to the Nehruvian socialist ideals of the older generation (Shammi’s father Prithviraj, the great stage actor and scion of the dynasty, was close friends with Jawaharlal Nehru) in the film’s opening segment, in which young Rajiv (Shammi), sole heir to a textile magnate’s fortune, scandalizes his widowed mother and uncle by announcing at a mill rally that, in this new era of “laborers’ raj,” he has decided that his family has already “made enough profits” and he now intends to give away lakhs of rupees to the workers. But mum and uncle Shyamlal-ji soon diagnose that the problem behind Rajiv’s largesse is not political, but libidinal: the poor oversexed boy needs to be married off ASAP (this assessment, made about three minutes into the film, appears to be accurate, and so we hear nothing further about workers, socialism, business etc.). But the prospective bride chosen by Mother does not please the idealistic son, who announces that he will wed only a girl of his own choosing, and tears off to points unknown in an oversize convertible before the elders can stop him.

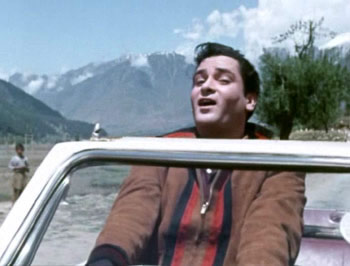

The destination is the Kashmir valley, that heaven-on-earth for north Indian plains dwellers, bone of violent contention between India and Pakistan, and longtime favored dreamscape of Bombay filmmakers. Here love is famously in the air (and water), and Rajiv sings of his hopes that it may strike him, in the road song Kissi na kissise, (“Sometime or other, somewhere or other, you have to give your heart to someone”). This leads to a chance encounter with a shy Kashmiri girl, Champa (Sharmila Tagore), who sells baskets of flowers to support her blind father Dinu (Anup Kumar). The impetuous boy soon loses his heart and then fairly throws himself—in trademark Shammi style (see below)—at the girl, who only gradually shows that she returns his affection. This requires three gloriously-picturised Islamicate courtship songs. The first (Taarif karun kya uski, “How shall I praise Him … Who has created your beauty?”) is staged as an aquatic boat-ballet on magnificent Dal Lake.

The second (Isharon isharon, or “All your signs...[of love]”) involves the obligatory rainstorm, and the lovers taking shelter in the home of an old peasant woman, who provides them with cute local outfits—a scene that led to God-knows-how-many honeymooners in hill stations dressing up as “Kashmiri” couples for keepsake photos. The third unfolds as Champa and her girlfriends are being transported to a local fair by the crude Mohan (Pran), a truck driver who has set his sights on Champa, and who moreover knows a secret with which he is blackmailing her poor father Dinu into giving her to him. To break through Mohan’s proprietary defenses, Rajiv concocts an elaborate ruse with the aid of his pal Chander: they pose as a Pathan couple seeking a lift (since the “wife” is pregnant). But “she” is in fact Rajiv, under the tent-like cover of a purdah-nasheen matron. Joining the other girls, “she” proceeds to shamelessly woo Champa with the song Subaan Allah hai (“Praise be to God!”), with Rajiv periodically unveiling himself while still retaining a drag persona of exaggerated female idioms and mannerisms. “Her” beefy stature and low voice are explained to the suspicious Mohan by invoking the stereotypic sturdiness of Pathans. Shammi is at his best in this hilarious gender-bender escapade, and to my mind, this song sequence, staged as Mohan’s truck rattles down the poplar-lined roads of the Vale and beneath snowcapped mountains, has to rank, with Chala chayya chayya from DIL SE and Kaanton se kheench ke anchal(a.k.a. Aaj phir jeene ki tamanna hai) from GUIDE, among the all-time-great-filmi-songs-performed-atop-moving-vehicles.

Even after Champa’s heart is won by Rajiv, there remains the problem of Mohan’s claim on her, and the matter of Dinu’s strange secret. The resolution, if contrived, is still clever, suspenseful, and satisfying—even when the scenery during a final, all-out fight between Mohan and Rajiv apparently cuts abruptly from Kashmir to the Deccan plateau. Mohan’s character deserves comment: arch-villain Pran is, like the heroine, coded as an ethnically-marked provincial; in this case, with a Kulu hat and (incongrously) rustic eastern-UP accent (“s” turned into “sh”), a deshi kurta showing under leather jacket (the latter a code for villains in this period), and a beedi smoked in clenched fist, peasant-style. But whereas regional marking is fine in the heroine (who will be “nationally integrated” through marriage to the hero), it is typically either ludicrous or ominous (or, as here, both) in a male. In Shammi’s world, good guys wear Teddy Boy suits.

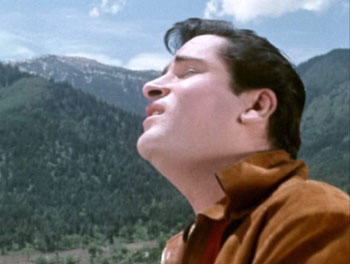

Sharmila Tagore is both credible and fetching as the innocent-but-not-dumb Champa, and she is nicely paired with Shammi here. As for the latter, even if one is not inclined to go the whole Freudian distance and agree with psychoanalyst and Hindi film buff Sudhir Kakar, who once wrote that the actor “used his entire body” as a symbolic you-know-what, this film will give you some idea of what the shrink had in mind. Shammi’s swooning, mannered, body language—eyes rolled back, head cocked to one side, and arms and legs flailing in all directions—hybridizes the indigenous sensuality of a Punjabi bhangra dancer (and he mimics one marvelously in the pounding, exuberant song Haay re haay, another standout number) or secular ghazal singer, with post-‘60s rock-n-roll gyrations. The result is that, when Shammi sings about love, he generally seems to be on the edge of an orgasm.

Reference: Sudhir Kakar, “Lovers in the Dark,” in Intimate Relations: Exploring Indian Sexuality. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989) pp. 25-41. (Reference to Shammi Kapoor is on p. 37).

[The EVP International “Classic Collections” DVD features a generally excellent print of the film; colors are deep and details crisp. Sound quality is good. Subtitles are shoddy, however – often wrong, sometimes missing, and entirely absent for songs. Still, one can manage. This is a visual and musical treat.]