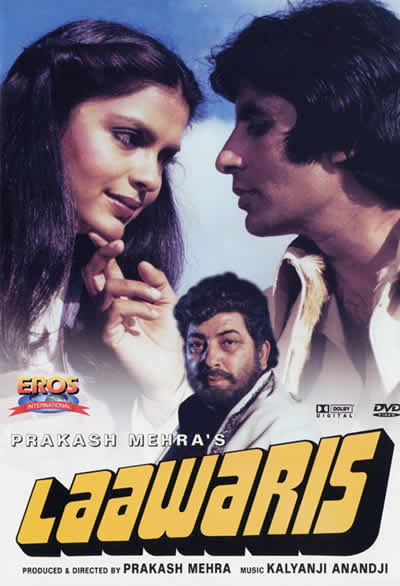

LAAWARIS

(“the bastard”; sometimes spelled LAWARIS)

1981, Hindi, 180 minutes

Produced and directed by Prakash Mehra

Story: Din Dayal Sharma; Screenplay: Prakash Mehra, Din Dayal Sharma, Shashi Bhushan; Dialogue: Kadar Khan; Lyrics: Anjaan, Prakash Mehra; Music: Kalyanji – Anandji; Cinematography: N. Satyen

Whether directed by Manmohan Desai, Prakash Mehra, or Yash Chopra, the classic Bachchan vehicles of the ‘70s and ‘80s delight in endlessly recapitulating the same set of heroic conventions, centered around an unbelievably resourceful and unflappably suave yet plain-folksy and substandard-Hindi-spouting protagonist (who is actually, in most cases, the lost, abandoned, or separated son of an industrialist or prince)—a sort of proletarian James Bond. This hero, nattily clad in the slums-eye-view of killer couture, makes impassioned speeches denouncing the hypocrisy of the rich and their abuse of the poor, while moving with ease in their corrupt society, eventually regaining his own rightful place in it (as well as a beautiful, rich bride who is, however, generally fairly peripheral to the plot). At the same time, this angry young hero remains a staunch upholder of the patriarchal family, a heartfelt champion of the unitary nation, and (usually, and despite outbursts against the hypocrisy of priests and mullahs and occasionally against God himself) a pious believer in divine intervention and in the essential fairness of fate. He is also generally his own comic sidekick (though he may have one or more additional ones in his orbit), alternating slapstick routines and ludicrous disguises with all-out fistfights and car chases, and impassioned and tear-stained declamations. Within these well-worn conventions, each successful Bachchan film attempts to introduce some new twist and to find innovative ways of exploiting the possibilities of the actor’s lanky physique, which anchors virtually every scene.

Here, Bachchan is Hira (“diamond”), the product of a pre-marital affair between a famous singer, Vidhya (Rakhee Gulzar), and a rich but callous prince-turned-businessman Ranvir (Amjad Khan). When Vidya dies in childbirth and Ranvir refuses to acknowledge the infant (who he had urged Vidya to abort), the baby is disposed of by a scheming lawyer who gives him to Vidya’s alcoholic chauffeur Gangu, with a wad of money and an order to disappear from the scene. Gangu soon blows the money on booze and then relentlessly exploits and abuses his “son,” who, as usual, appears in a series of vignettes played by Bachchan-resembling child actors of increasing age. Despite all vicissitudes, Hira grows from strength to self-made strength—even his name is self-chosen, taken from a stray dog that befriended him as a child (cf. Raju in AWARA)—though his plucky self-confidence is always edged with anguished self-pity for the countless wrongs he has suffered. Eventually he discovers that he is not Gangu’s son (though the drunkard refuses to tell him who his real parents were), but a laawaris: an “orphan,” but also a term used for property that is “unwanted” or “unclaimed.”

After a brief stint of factory work (which he performs dressed in a skin-tight zippered jump suit that alludes to laborers’ garb while looking suitably stylish and mod), Hira displays his considerable talents in a brothel brawl, accompanied by the comic disco song Aapka kya hoga (“What will you do?”), earning the grudging admiration of his nemesis, the dissolute playboy Mahinder (Ranjeet), whose wardrobe favors leather suits and high boots. It turns out that Mahinder runs a timber-baron empire in scenic Kashmir for his own father, a prince who has retired from the business world in order to devote his life to charitable service, especially to the welfare of abandoned and illegitimate children—and who is, of course, none other than the reformed Ranvir, Hira’s own real father, now tormented by guilt for his past misdeed. Mahinder puts Hira in charge of his most obstreperous millhands (among whom Hira quickly establishes himself as alpha male) and also gives him special assignments like demolishing hutments and a Hanuman temple to make way for a “five star hotel.” Hira spares the temple and leads the homeless poor to the mansion of Mahinder’s girlfriend, where he contrives to have them accommodated while compelling Mahinder to build a “model town” for them. Eventually he runs afoul of Mahinder and earns the affection of the pious Ranvir, who disapproves of Mahinder’s misdeeds but, naturally, does nothing to check them. Hira himself develops a love-hate relationship with Ranvir, to whom he is strangely attracted, as well as love interest in the form of Mohini (Zeenat Aman), a spoiled vixen he quickly tames, who is also (unbeknownst to him), the daughter of the very lawyer who disposed of him as an infant. He also champions the cause of a potter whose sister Mahinder tried to ravish, and when the poor potter loses his arms (echoing MOTHER INDIA and SHOLAY) Hira even does a stint of expertly shaping clay on the wheel (reminding me of the admiring comment a ditzy New York matron is supposed to have made, on hearing the rumor that conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein was bisexual: “Is there anything that man can’t do?!”).

Such vignettes of the hyper-sufficient Bachchan hero (e.g., his knowledge of numerous Indian languages and the characteristic mannerisms of their speakers) are the real highlights as the film winds its circuitous but predictable course toward father-son reconciliation. The pièce-de-resistance in this respect is unquestionably the folkish spoof song Mere angane mein (“In my courtyard”), the film’s standout hit, improbably sung in the opening segment by Vidhya as a cabaret number (and ostensibly, a popular tune that became a heart-lifting inspiration to her lost son throughout his troubled childhood), and then brilliantly reprised near the climax by Hira himself (with Bachchan providing his own singing voice), and featuring a series of drop-dead drag impersonations, accompanying crudely comic verses (unsubtitled, unfortunately, as are all the film’s songs) about the merits of various sorts of wives:

The fellow whose wife is too tall,

he too is well known.

Just prop her against the wall

and who needs a ladder!

The fellow whose wife is too fat,

he too is well known.

Just lay her down on the bedding

and who needs a mattress!

The fellow whose wife is too dark,

he too is well known.

Just gaze at her long enough

and who needs eye shadow!

The fellow whose wife is too fair,

he too is well known.

Just sit her down in a room

And who needs electricity!

The fellow whose wife is too small,

he too is well known.

Just take her in your lap

and who needs a kid!

This catchy ditty is (within the film) hugely enjoyed by mixed-gender audiences, including women of the various caricatured descriptions. Other cultural points that may puzzle the novice foreign viewer include Ranvir’s unwillingness, despite his tormenting guilt, to acknowledge Hira as his son even after he knows his identity—a weakness that is supposed to reflect Ranvir’s helplessness before the “standards of society” which he dare not challenge. Then there is the fact that even heinous crimes like murder and rape, when committed by a son, can be summarily pardoned if the culprit utters a self-abasing “maaf karna!” (“Forgive me!”) before his father, whose honor, it seems, is the only thing that can ever really be seriously injured in this moral universe. Upholding this is the constant preoccupation even of a superhero like Hira, who abruptly and tellingly shifts from his usual cocky and assertive mode (when dealing with women and other men) to one of cowering obsequiousness in the presence of the Patriarch. And though glamorous women abound, it is the bear-hug of males, affirming their indissoluble blood bond, that provides the film’s devoutly-desired consummation.

[The Eros International/Digital Entertainment Incorporated DVD of LAAWARIS features an excellent quality print and fair-to-middling subtitles, though its seven song sequences lack even these.]