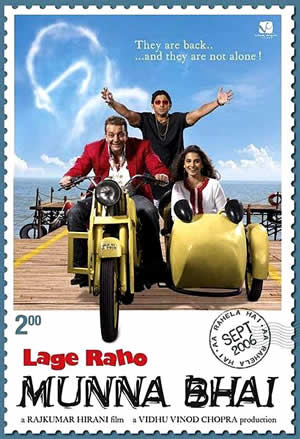

LAGE RAHO MUNNA BHAI

(“Keep at it, Munna Bhai,” 2006, Hindi, ca. 145 minutes)

Directed by Rajkumar Hirani

Produced by Vidhu Vinod Chopra

Screenplay and dialogues: Rajkumar Hirani and Abhijat Joshi; Lyrics: Swanand Kirkire; Music: Shantanu Moitra; Production designer: Nitin C. Desai; Choreography: Ganesh Acharya; Cinematography: C. K. Muraleedharan

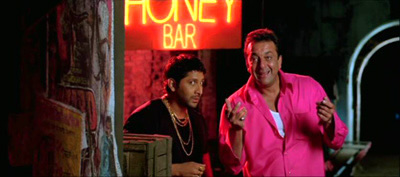

This is less a “sequel” to 2003’s successful comedy, MUNNA BHAI M.B.B.S., than a reworking of its essential plot—about a lovable petty thug wooing a woman of higher educational and social status through an elaborate masquerade that is threatened by authority figures, yet ultimately triumphing through his qualities of emotional openness and “heart.” Both films use sumptuous cinematography and the (now) usual digital tweaking to make Mumbai appear a candy-colored consumerist utopia—Miami's South Beach with an occasional god-poster. Both feature inventive sight-gags and many of the same actors, and both, despite their visual overload, also rely heavily on rapid-fire and deftly-delivered dialogue in substandard (but now, and partly through these films, increasingly standard) tapori Hindi peppered with English words and phrases to convey the infectious charm of the main characters: Munna (“kid”), a hulking yet boyish bhai(literally “brother,” but “hoodlum/gangster” in Mumbai slang, played by Sanjay Dutt), and his compact, resourceful sidekick and majordomo, “Circuit”/Sirkeshwar (Arshad Warsi). The versatile Boman Irani, who played Munna’s comical nemesis, the bald and high-strung Dr. J. C. Asthana, in the first film, reincarnates in the comparable slot here—this time as a hirsute, paunchy, and thoroughly corrupt Sikh real estate developer, Lakbir/“Lucky” Singh.

Jimmy Shergil returns as yet another sad-eyed young man—no longer a Muslim boy dying of cancer, but a guilt-stricken Goan who has lost his dad’s nest-egg on the stock market. Suman/“Chinki,” the young medical student whose wooing by Munna largely drove the plot of the first film and who he apparently wed at its conclusion, has vanished without explanation, being replaced by another gorgeous and unattainable heroine: the call-in radio DJ, Jhanvi (per the English subtitles, although this name, an epithet of the Ganga River and goddess, would be more correctly transliterated Jahnvi), played by Vidya Balan, an actress who, like Gracy Singh in the first movie, could easily be actor Dutt’s daughter. Since Munna’s parents, who similarly loomed large in the original film, are also gone (though the audience, of course, understands, that Sunil Dutt, the star’s real-life father and his fictional dad in the earlier movie, passed away in the interim), it is as if we are presented, à la the Hindu purana narratives, with a Munna Bhai avatar in an alternate universe or a differentkalpa (cosmic time cycle)—moving amidst the same basic circle of role-players and repeating the same salvific mission (to improve himself and better the world through somewhat loopy “love”), but with minor variations—perhaps to avoid divine boredom.

But what works for (Hindu) God doesn’t often work for filmmakers, and the formulaic plotline here might seem like a recipe for a dud sequel—and yet, LAGE RAHO MUNNA BHAI scored an even bigger box office success than its precursor, rivaling RANG DE BASANTI for the status of the most-acclaimed and most profitable film of 2006, and garnering four Filmfare awards. The explanation for this, I propose, lies partly in the Munna-Circuit chemistry and linguistic hijinks—which are easily satisfying enough for two movies (a planned third installment was on ice in 2007 because of Sanjay Dutt’s imprisonment on a charge of possessing illegal weapons and possibly supplying them to gangsters-cum-terrorists), but also in another sort of appeal to the zeitgeist of contemporary India. For the film’s major innovations are to shift the sphere of Munna’s emotion-dispensing avataric activities from the medical establishment of an allopathic teaching hospital to the realm of media (especially call-in DJ radio, one of the country’s new obsessions), and to replace Munna’s mother and her panacea-like jaadu ki jhappi (“magic hugs”) with a populist send-up of the Father (and, in his nurturing and androgynous way, also “Mother”) of the Nation, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, here as an avuncular apparition visible only to the hero—imagine (in American terms) a combination of, say, Abraham Lincoln and "Harvey" (the six-foot invisible rabbit shadowing Jimmy Stewart in Henry Koster’s celebrated 1950 film).

This is one of the more remarkable turns in the public re-appraisal of Gandhi-ji that began to be reflected, in a more serious register, in such fin-de-siècle films as HEY RAM (2000) and THE LEGEND OF BHAGAT SINGH (2002). Munna’s “Bapu” (an endearing kinship term roughly equivalent to “Pops” or “Gramps”) has only a slight physical resemblance to the genuine article, but the impersonation is enhanced by costume and gait, and by dialogue that, at its best, suggests some of the sharp and self-deprecating humor for which Gandhi was known, as well as his quirkily principled interventions into the lives of his disciples. Munna quickly dubs Gandhi’s nonviolent and truth-based approach to problem solving (known in formal Hindi as Gandhi-vaad or “Gandhi-ism, Gandhian ideology”) “Gandhi-giri,” using a suffix commonly applied, in Bombay slang, to words associated with criminal behavior (e.g., gunda-giri, “hooliganism, thuggery”). This incongruous and hard-to-translate compound, linking an exalted surname with a rather disreputable term (“the Gandhi-racket” perhaps suggests something of the resonance) rapidly became, like much else connected with the film, a national sensation (more about this below).

|

Like its predecessor-film, LRMB opens with a kidnapping caper, this time involving a building inspector employed by the Mumbai municipality, who is picked up by Circuit and delivered to Lucky Singh, to be both threatened and bribed into expelling legal tenants from a beachside house that Singh wants as a wedding present for his daughter. Though guns are brandished, no one is hurt, thus safeguarding the film’s basic haasya rasa (comedic mood)—but also inviting casual enjoyment, in an entertainment context, of the sort of routine criminal harassment that, for many Indians, is certainly no joke. Munna himself is absent from this sequence, and we soon learn that it is because of a new daily ritual of sitting on a dock and soaking up Jhanvi’s cheery “Good morning, Mumbai!” show. When the DJ announces that the next day, October 2nd, will be celebrated with a call-in quiz on “Bapu,” whose birthday it is, the winner of which will be a guest in the studio the following day, Munna resolves to be that winner—but first, of course, he has to find out who “Bapu” was. Circuit isn’t sure, either, but quickly gathers the information that he was M. K. Gandhi, the “skinny but brave dude” who opposed the British and helped win the nation its freedom, though, alas, his teetotaling resulted in his birthday being inconveniently made a “dry day” (sale of alcohol prohibited). Obviously, winning Jhanvi’s quiz may require a more in-depth knowledge of Gandhi than this, so, as in the previous film (when a brainy Parsi doctor was forced to sit for Munna’s medical school entrance exam), a panel of Gandhi experts are rustled up, held hostage, and then bribed with consumer “door prizes” for each correct answer fed to Munna, who, of course, wins handily. In the studio, Jhanvi proves to be even more beautiful than her voice, but her probing on-air questions oblige Munna to weave a yet more tangled web of deceit, now posing as a college professor of Gandhian studies, whose lapses into street slang are excused as a conscious strategy to engage his young pupils. Learning that Jhanvi lives with her grandfather and a circle of his elderly male friends, all of whom have been expelled from the homes of their middle-class children, in one of those seaside estates that nice people in Bombay films incongruously manage to score (cf. MR. INDIA)—a place dubbed, using cricket lingo, “Second Innings House”—Munna magnanimously offers to pay a visit and give the oldsters a Sunday lecture on Gandhi-ji. |

|

|

|

Alas, his team of experts can hardly be expected to accompany him, so Munna bites the bullet and enters the Gandhi Memorial Library—where he is, the astonished caretaker announces, the first visitor in years—to bone up on the activities of the “skinny but brave dude.”

This leads to his encounter, after several sleepless nights, with the Bapu apparition who will guide him, periodically, through the remainder of the film, helping him to charm both Jhanvi and her aged boarders, and ultimately, to deal with the greedy Lucky Singh, whose coveted illegal real-estate grab is, of course, none other than Second Innings House.

Diversions enroute to the inevitable happy ending include a drunken dream(like) sequence in which Munna tells Circuit that his marriage to Jhanvi is “basically a done deal!” (Samjho ho hi gaya—a visually inventive song picturisation), and an idyll in Goa that resembles an airline “weekend getaway” TV ad (presented through the song Aane chaar aane, “A mere quarter [of life remains, so don’t waste it]”). |

|

The coincidence that the Gandhi-extolling LAGE RAHO MUNNA BHAI shared top box office and cinematic honors in 2006 with RANG DE BASANTI (hereafter RDB), a film that celebrated the violent young revolutionaries whom Gandhi opposed, invites reflection on some common features of both. Besides indicating that retrospective analysis of the Freedom Struggle still retains, with the right treatment, robust box office potential, the success of these films notably sparked copycat activism in support of a range of causes, in which (mostly young) protestors engaged in candlelight marches and vigils (à la RDB), or various forms of LRMB-inspired “Gandhi-giri,” such as sending bouquets of flowers to oppressors, with “get well” messages. Both clearly tapped into a middle-class perception that the beneficiaries of market liberalization do owe something to the victims of the lingering and endemic corruption of the Indian state and some of its most powerful citizens. But both also highlight the changed post-liberalization landscape of the nation, in which mass media other than cinema have acquired major clout. Both show, at climactic moments, the potential of, especially, radio to sway emotions and galvanize disparate audiences. As the young assassins of the Indian Defense Minister, in RDB, succumb one by one to the assault of a government SWAT team on the All India Radio studio in which they are holed up, or as (in a more benign scenario) Munna Bhai wrestles on-air with Lucky Singh to save Second Innings House, the editing repeatedly cuts away to show mesmerized audiences huddled around radio sets, with the mise-en-scène carefully composed to suggest socio-economic and religio-cultural diversity; close-ups often show these intent listeners cheering, or wiping away tears. Such montages appear to be a new twist on the old Hindi cinematic preoccupation with representations of the nationalist slogan and agenda of “unity in diversity,” often achieved through the assemblage of an assortment of “types” exemplifying different ethnic or religious communities (cf. AMAR AKBAR ANTHONY or LAGAAN). In these newer films, the unified nation is evoked less through maps, slogans, or stereotyped personae than through representations of mass media, and of their power to forge (in Benedict Anderson’s oft-quoted phrase) an “imagined community”—at least for the duration of a broadcast. The message seems to be that the nation may be diverse and its problems daunting, but, as long as its people continue to tune-in to the same talk shows, there is hope for the future. Let’s hope so. |

|

[The Eros DVD of LAGE RAHO MUNNA BHAI offers subtitles for both dialog and songs, but English-speaking viewers should be warned that these reflect translation decisions that are not always felicitous. Although some of the translator’s ambitious efforts to render Munna & co.’s slang into comparable American idioms come off reasonably well (e.g., Munna’s constant vocative Mamu is rendered “dude”), others fail badly, producing highly misleading results. The worst examples of these substitute (supposedly) equivalent American names and personalities for Indian ones, as when the names of moviestars “Shah Rukh Khan and Dilip Kumar” turn up in the subtitles as “Brad Pitt and [Robert] Redford,” or when clever Hinglish puns are replaced by irrelevant and less-than-clever English word-play.]