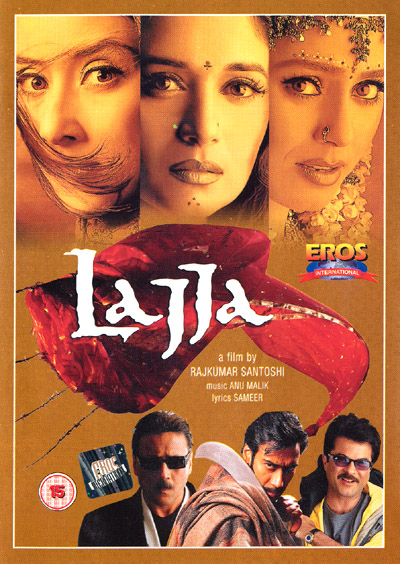

LAJJA

(“Shame, Modesty,” Hindi, 2001, 202 minutes)

Produced and Directed by Rajkumar Santoshi

Story and screenplay: Rajkumar Santoshi; Dialogue: Rajkumar Santoshi, Ranjit Kapoor; Lyrics: Sameer, Prasun Joshi; Music: Anu Malik, Ilaiyaraaja; Cinematography: Madhu Ambat; Choreography: Ganesh Acharya; Art direction: Nitish Roy

Rajkumar Santoshi’s indictment of Indian patriarchy and misogyny is nothing if not ambitious: packed with major stars and displaying lavish production values, it yet more significantly boasts an ingenious premise, an elevating and timely message, and several scenes of real brilliance. The film’s remarkable central conceit is to weave together the stories of four young women, each of whom bears a name that is a common epithet of Sita—the heroine of the Ramayana and a woman whose treatment by her husband has elicited sympathy and provoked public debate for millennia. True to their namesake, each of the four heroines has a bad experience with men, each reflecting a different aspect of the South Asian gender hierarchy and the hypocrisy and cruelty that it generates. This would already be a lot to pack into a film, even one of this length, but when the director (perhaps in a well-meant effort to make his bitter moral pill go down easier with male cinemagoers) piles on additional stock elements of the Bombay masala tradition—a fast-paced chase featuring a relentless villain accompanied by bumbling, comical sidekicks; a dapper thief and con-man who evades the police by crashing a high-end wedding; and a swashbuckling avenger who takes on the forces of rural feudalism with sword and fists—he concocts a cinematic smorgasbord that may strike some viewers as indigestible or, worse still, as just another fil-um in which, in the end, distressed damsels are rescued by resourceful men.

After a credit sequence in which a digitally-generated red dupatta floats around the night-lit towers of (pre-9/11) New York City, to the accompaniment of grandiose music performed by the Budapest Radio Symphony Orchestra, we meet a super-rich NRI couple, Vaidehi (“the girl from Videha” [Sita], played by Manisha Koirala) and Raghuveer (Jackie Shroff; his character likewise bears a common epithet of Rama, the “hero of the Raghu lineage”). Whereas the latter has embraced the (imagined) Big Apple executive lifestyle of booze, discos, and babes, the former craves tradition, domesticity, and emotional intimacy. When things break down and he becomes physically abusive, she flees to her parents’ flat in Mumbai, where she finds a chilly reception and the usual lectures about Patience and Fortitude. Meanwhile, Raghuveer has a car crash that renders him incapable of fathering children and then learns from the family doctor (who had given Vaidehi a routine blood test just before she left the US) that his estranged wife is pregnant. Craving santaan (“progeny”), Raghu and his father plot to get Vaidehi back, use her as an “incubator” for their hoped-for heir, and then dispose of her afterwards—by murder, if necessary.

When Vaidehi (who has been warned of the plot by a friend) escapes the comical lackey who is supposed to bring her back to NY (Johnny Lever as an upwardly-mobile Muslim named Fakiruddin), Raghu rushes to India to join in the chase, which occupies, off and on, the remainder of the film.

Fleeing her pursuers (who thanks to Raghu’s wealth and political connections soon include masses of police), Vaidehi is befriended by a high-class thief (Anil Kapoor), who robs rich merchants by feeding them drugged biscuits—but only in order to raise the cash needed to secure a respectable job in the Persian Gulf. Together they crash a wedding in which Maithili (“the girl from Mithila” [Sita], Mahima Chaudhary) is being married to a college sweetheart, even as the groom’s greedy father (carefully observed by the sharp-eyed thief, who acts as guiding Virgil to Vaidehi’s Dante in this glittering pre-nuptial Purgatory) attempts to extort additional dowry from the bride’s hard-pressed parents.

Though wedding-as-spectacle (exemplified by the song Saajan ke ghar, “to the Beloved’s house”) threatens to overwhelm this subplot, the many vignettes of arrogant and predatory groom’s people and downcast and subservient bride’s people (which, alas, are only slight exaggerations of a common middle-class norm in north India) and the rousing denouement, in which Maithili and her elderly aunt tell off the would-be father-in-law and his yes-man son, keep the film (sort of) on track.

Vaidehi’s next stop is a provincial town in central India where she is befriended by Janaki (“King Janak’s daughter” [Sita]; Madhuri Dixit), a self-confident actress in a nautankti (folk theater) troupe. Like Vaidehi, Janaki is two months pregnant, but although unmarried, she is secure in her belief that the baby’s father—the troupe’s leading man, Manish—will soon do the right thing by her, and they will move to Delhi, where Manish has been offered a role in a television serial. Meanwhile, she deftly fends off the lecherous Purushottam (“the exemplary man,” another allusion to Rama), the owner of the troupe, who lusts after his young actresses while hypocritically preaching a particularly austere strii-dharma (“womanly virtue”) to his homebound wife. After being humiliated by the proud Janaki, Purushottam takes his revenge by planting in the mind of the none-too-bright Manish the suspicion that the child Janaki is bearing might not be Manish’s own. This obvious Ramayana allusion leads into the film’s most inspired sequence, in which Manish and Janaki quarrel backstage while simultaneously performing the climactic events of a Ramlila-like production of Valmiki’s story, culminating in Sita’s agni-pariksha(test of purity by fire) in which Janaki does what many Ramayana audiences have long wished her namesake would: departs from the script to put Rama/Manish in his place.

Spiritedly acted by Madhuri, this remarkable scene (Chapter 14 on the DVD) alone is worth the price of admission to Lajja, and it offers (among other things) a notable potential resource to educators teaching the cultural message of the Ramayana and its continued and contested interpretation. The brutal revenge-beating of Janaki by a “dharma-defending” mob (including saffron-clad sadhus) hired by Purushottam, coupled with the arrival of Raghuveer and his minions, leads to Vaidehi’s continued flight eastward, now aboard the “Avadh [Ayodhya] Express.”

But when the train is attacked by a gang of sword-wielding dacoits in the hire of a corrupt zamindar named Gajendra (Danny Denzongpa), Vaidehi is rescued once more, this time by a black-clad Robin Hood named Bulla (Ajay Devgan), Gajendra’s sworn enemy: a Ninja-like champion of the oppressed, whose battle cry is Jay Mata ki! (“Victory to the Mother Goddess!”), and who is easily capable of taking on a dozen or more armed assailants.

He delivers Vaidehi to Ramdulari (“Rama’s darling” [Sita]; Rekha), a self-possessed village dai or midwife, who tenderly ministers to rural women and tongue-lashes their men when they attempt female infanticide. Though low-caste and widowed, Ramdulari is a dynamo who is teaching herself English and educating her only son, Prakash, in a nearby town where he can learn computer skills that will benefit the entire village. Alas, he is also romancing the zamindar’s daughter Sushma, thus rousing Gajendra’s ire, which is further sharpened by the realization that the woman Ramdulari is sheltering is a runaway wife whose husband is offering a huge reward for her capture. Once again, Bulla’s timely intervention saves Vaidehi, Prakash, and Sushma from the combined forces of Gajendra and Raghuveer, but it proves too late for Ramdulari, who has been taken captive by Gajendra’s thugs.

Ultimately, Vaidehi herself confronts the brutal landlord-turned-politician at a Nuremburg-like political rally, delivering an impassioned speech that raises the consciousness of a whole army of long-suppressed women. More miracles ensue, not least of which is a tidy coda that brings most of the (surviving) characters back to happy domesticity in Ayodhya-on-Hudson—a fate that the actual Sita never quite achieved. (Whew.) The prolixity of LAJJA’s sprawling plot is underscored by the fact that this three-hour-and-twenty-two-minute monster of a movie contains a mere three songs—two of which (the cabaret number Aiye aajaiye and the folkish Badi mushkil) are almost entirely extraneous to the story.

Near the end of his peevish and mostly predictable diatribe against the Bombay film industry, The Politics of India’s Conventional Cinema, Marxist critic Fareed Kazmi details his own antidote to what he sees as its soporific capitalist message: not the alternative “art cinema” (which he likewise castigates for its elitism and self-absorption), but a robust yet politically-charged mainstream cinema that would be “direct, straightforward, and easily understandable,” and also “fast-paced, tightly-knit, slickly edited,” and “so structured that it provides pleasure to the audience, rather than merely lecturing it” [sic.] (Kazmi 1999:235). A film like LAJJA indeed appears to be an attempt at filling Kazmi’s edifying prescription, yet with all that it has going for it, Santoshi’s movie repeatedly risks degenerating into a burlesque of fast-paced but mismatched “items,” suggestive of, say, a cinematographically updated and politically-more-correct Manmohan Desai who has succumbed to the temptation of taking himself too seriously. Shouting its (worthy) message in our faces, LAJJA fumbles in delivering it, and in the process seems to collapse under its own moral, narrative, and visual weight. And given that its heart is (more or less) in the right place, this is a real…shame.

Reference:

Fareed Kazmi, The Politics of India’s Conventional Cinema: Imaging a Universe, Subverting a Multiverse. New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1999.

[The Eros International DVD of LAJJA is of good visual quality and includes decent English subtitles for both dialogue and songs.]