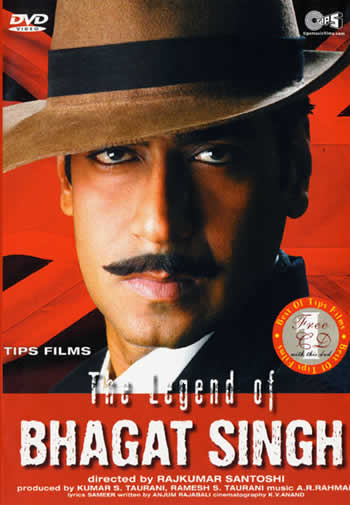

THE LEGEND OF BHAGAT SINGH

(2002)

Hindi and English, 155 minutes

Directed by Rajkumar Santoshi

Produced by Kumar S. Taurani and Ramesh S. Taurani

Written by: Anjum Rajabali; Hindi dialogues: Piyush Mishra; English dialogues: Anjum Rajabali; Music: A. R. Rahman; Lyrics: Sameer; Art direction: Nitin Chandrakant Desai; Choreography: Ganesh Acharya, Jojo Khan; Cinematography: K. V. Anand.

Bhagat Singh, a twenty-three year old revolutionary from Punjab who was hanged by the British on March 23, 1931, became one of the most celebrated martyrs of the Indian independence movement. A photo of him with a neatly-waxed mustache and rakish fedora was the basis for a widely circulated icon that remains instantly recognizable within the teeming polychrome pantheon of Indian poster art, and that, like similar icons of Subhash Chandra Bose (who raised an “Indian National Army” that allied with the Axis powers against the British during the Second World War), celebrates those sons of India who sharply disagreed with Mahatma Gandhi’s emphasis on nonviolent resistance to colonial rule. Bose and Bhagat popularly represent militant struggle and the embrace of shakti or physical force—the darker, bloodier counterpart to Gandhi’s bhakti (or “devotion”)-inspired emphasis on “truth-force” (satyagraha). However, unlike Bose, who was attracted to fascist ideology, Bhagat Singh was a committed Marxist, an admirer of the Bolshevik Revolution, and a proponent of class struggle to avoid replacing “white sahibs” with brown ones on the achievement of Independence. Though Gandhi has always been more venerated and visible internationally, the fact remains that his biography and legend tells only part of the story of the Independence struggle, and his global prominence has tended to obscure the fact that the often violent deeds and will-to-martyrdom of his political opponents have likewise continued to be admired by the majority of Indians.

All the same, the appearance of no less than three cinematic biographies of Bhagat Singh within a few weeks of one another in 2002 (in addition to the film reviewed here, there were also SHAHEED-E-AZAM, directed by Iqbal Dhillon, and 23 MARCH 1931 SHAHEED, directed by Guddu Dhanoa; in addition, a TV biopic was directed by Ramanand Sagar in the same year, and a fifth film production was completed but unreleased) was a remarkable phenomenon even in the world of Mumbai filmmaking (which displays the same tendencies toward trend-conscious, copycat production that obtain in Hollywood), particularly given the fact that historical films have been a rarity overall. Although none of these films achieved hit status, their almost simultaneous release surely warrants comment—which will be offered shortly, after a synopsis and review of what appears to be the best of the lot: Rajkumar Santoshi’s ambitious LEGEND, featuring impressive cinematography and period recreations and a notable performance by Ajay Devgan as Bhagat Singh.

In a way—and I mean no trivialization or disrespect to the momentous subject matter—this could be an Amitabh Bachchan film of the late 1970s (and indeed, several Indian reviewers have praised Devgan’s portrayal of Bhagat Singh by using the phrase “angry young man”). After an opening frame in which the frightened Brits try to hastily dispose of the bodies of Bhagat and two co-conspirators, and Bhagat’s father (Raj Babbar) watches angry demonstrators confronting Gandhi with questions for which the Mahatma has no effective answers, we begin a flashback (as if in the father’s mind) to little Bhagat being traumatized by glimpses of imperial sadism: the flaying of political prisoners on the streets, and the massacre of hundreds of civilians in the Jalianwala garden by General Dyer’s troops in 1919 (a horrific sequence rendered in artfully surreal, if now-stereotypical, montage and slow motion). As in many an Amitabh film, the child-hero is betrayed or abandoned by a father figure—here Gandhi-ji, who frustrates Bhagat’s budding nationalism when he abruptly calls off the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1921 following the burning of a police station.

And again, as in a classic Bachchan film, the morphing of this traumatized lad from boy to man is accomplished by a song, the “establishing song” of the adult hero; here, Pagadi Sambhal (“Hold fast to your turban”) in which the college student Bhagat turns an innocuous school play presented for the amusement of British officials into an angry denunciation of their rule and a rousing assertion of resistant Indian manhood. (Here, as throughout, A. R. Rahman’s powerful rhythms accompanied by athletic male ensemble dancing invoke an Indianized worldbeat that—as in the fight songs of LAGAAN—flirts with a seductive, chest-thumping neo-fascism.) And as in many a Bachchan film, there is a touch of love interest, but only in the form of a marginalized heroine (Amrita Rao) who can never be permitted to distract the mission-bent Angry Young hero: here, she is a demure bride chosen by Bhagat’s parents, who gives her heart to him even as he has given his to the Motherland. He also finds dosti or close male friendship through his idealistic pals Sukhdev and Rajguru (energetically played by Sushant Singh and D. Santosh), who will eventually die with him. Again, as in certain A. B. vehicles, the adult hero finds a tough, worldly-wise mentor (in fiery Marxist Chandershekhar Azad, played by Akilendra Mishra) whose acceptance he gains through an ordeal involving both wit and pain—here, snappy dialogue and the (commonplace) seizing of a sharpened blade to deliberately draw blood.

But, of course, this isn’t an Amitabh Bachchan film. There can be no neat, happy resolution to the ensuing march of historical events—Bhagat’s participation in the murder of a Lahore policeman involved in the brutal beating of nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai; his tossing a “harmless” bomb in the National Assembly chamber in New Delhi to dramatize his movement’s aims; his subsequent imprisonment, torture, and hunger strike; and his conviction and death sentence for the policeman’s murder following the defection of one of his erstwhile comrades—except, of course, in all of us implementing Bhagat’s dream of continuing theInquilab or anti-communal, anti-capitalist “Revolution.” This seems to be the filmmaker’s idea, and he adds a small-print message, in English, that flashes by awfully quickly at the end, asking whether Indians have betrayed the ideals for which Bhagat gave his life. Doubtless many of them have, but an equally valid question is whether the film itself unwittingly does so, by the very fact of folding the complex political message of a youthful radical into the body of an obligatory six-songs-plus-fight-sequences commercial film. (I’m all for doing this, by the way. I’m just not sure that this film, despite notably good intentions, pulls it off.)

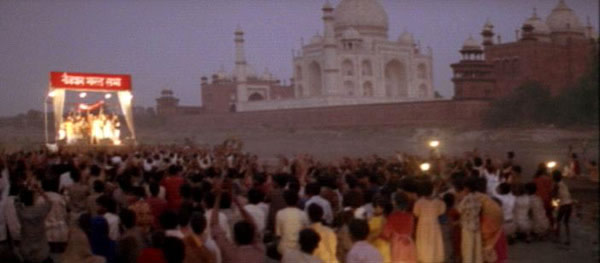

There are obvious efforts to get an anti-communal message across through both dialog and song (as in the picturization of Des mere, “O My Country,” the revolutionaries’ lovesong to Mother India, which places them in an array of attractive locales but also shows them staging an outdoor drama to promote Hindu-Muslim unity), and there is a sharp questioning of the motives of Gandhi and other Congress leaders. Yet cinematic convention sometimes seems to overwhelm ideological intent, and it is easy to lose sight of the fact, for example, from the alternately raucous and touching scenes of dosti in courtroom and jail—and these are boys who sing together beautifully even after sixty days on a hunger strike, and while marching to the gallows—that Bhagat Singh was not just a soulful idealist or Christ-like martyr, but an earnest young intellectual who wrote prolifically and from an ideological perspective that would have seriously challenged most of his fellow Indians (one of his final essays from prison was “Why I am an Atheist,” which is seemingly alluded to in a single line when he is on the scaffold, and tells the weeping prison cook that he “doesn’t believe in God”). The film does suggest that Bhagat’s fearless death gave him a mass following that frightened Congress leaders and forced them to be more aggressive in their stance toward the British, thus accelerating the pace of the Independence struggle.

If I have already implicitly argued that one reason for the cinematic embrace of Bhagat Singh is that his legend, at least as adapted by Santoshi, bears a resemblance to an archetype created in the mainstream cinema of the 1970s and ‘80s, I must still address the question: Why so many Bhagat Singh films at the same historical juncture? Apart from the most obvious incentive—the phenomenal success of 2001’s historical fantasies LAGAAN and GADAR, which some in filmistan interpreted as a signal that the public was suddenly hungry for celluloid sendups of the independence struggle and Partition—one can observe that the celebration of Bhagat Singh’s life and death constitutes part of the increasingly open questioning, in the aftermath of the collapse of the Congress Party in the early 1990s and the rise of Hindu nationalism as a potent political force, of the hallowed Gandhian legacy, now often problematized by critics both on the right and left. The portrayal of Gandhi as less a haloed saint and more of an idealistic but flawed socio-political leader—a man whose well-intended moves sometimes had negative consequences, or who even made serious mistakes—has already been seen in Kamal Haasan’s controversial HEY! RAM (2000), an ultimately pro-Gandhi epic that nonetheless ventures deeply and sympathetically into the minds of his staunchest political enemies (and eventual assassins): the votaries of Hindutva.

In Santoshi’s LEGEND, the revisionist questioning, this time from a leftist perspective, goes much further, with an authentic-looking Gandhi who appears alternately glib and unsure of himself—and the filmmaker more than once implies that his stress on nonviolence (e.g., to striking workers and angry peasants) played directly into the hands of both the British overlords and the Indian rentier classes. Ultimately he appears to collude with the hated Brits in sealing the fate of the film’s idealistic young hero. Such an interpretation of the Mahatma’s actions in a mainstream film would have been unthinkable a short while ago—but times have evidently changed.

From a more ominous perspective, the sheer glorification of youthful, macho violence—of “fighting back” and “teaching lessons”—as the solution to political problems, though projected back onto a venerated era of heroes and martyrs, and deployed against the persons of demonized Britishers (played by shabby-looking, disposable Western actors and extras—some with Eastern European accents—who seem to be wishing they were in a different film), appears a troubling cinematic move in a BJP-ruled India that has in recent years seen unprecedented “communal” bloodbaths (in reality, nearly always anti-Muslim pogroms and “ethnic cleansings”), as well as regular bouts of atomic saber rattling toward neighboring Pakistan. Indeed, the Bhagat Singh films, recalling the halcyon days of the Independence struggle, surely seek to capitalize on the patriotic mood that gripped middle-class India following the terrorist attack on Parliament in December, 2001 and the tense military face-off with Pakistan during the summer of 2002. Santoshi, of course, has other and more laudable agendas, noted earlier, that serve to somewhat counterbalance these trends, yet as I indicated there is a risk that they collapse beneath the weight of the film’s more simplistic and conventional visual program.

[The TIPS Films DVD of THE LEGEND OF BHAGAT SINGH is of excellent quality. Subtitles are above average, and are provided for song lyrics.]