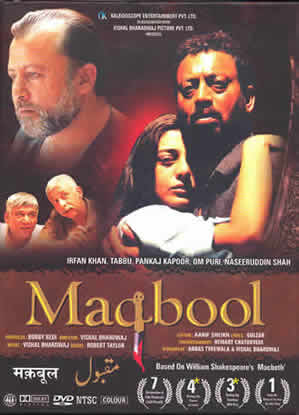

MAQBOOL

(Hindi, 2003, 126 minutes)

Directed by Vishal Bhardwaj

Produced by Bobby Bedi; Screenplay: Abbas Tyrewala and Vishal Bhardwaj; Dialogues: Vishal Bhardwaj; Lyrics: Gulzar; Music: Vishal Bhardwaj; Cinematography: Hemant Chaturvedi

Films with criminal protagonists permit directors and audiences to vicariously experience lifestyles involving extraordinary levels of danger, violence, and ill-gotten luxury, secure in the expectation that they will (normally) be atoned for in the end. Although detective and crime dramas in Bombay cinema began appearing in the silent films of the 1920s, a criminal antihero was relatively rare (with the exception of occasional films featuring noble dacoits or rural bandits; cf. GUNGA JAMUNA, 1961) until the 1970s, when such a role, usually explained as the result of childhood trauma or deprivation, became associated with the emerging “superstar” persona of Amitabh Bachchan (cf. DEEWAR, DON). The backdrop to such films was generally the “black” economy of smuggled goods and untaxed wealth that flourished on the underside of the Congress government’s bureaucratic “license Raj.” With the gradual eclipse of the latter, during the 1980s and early 1990s, by “free market” ideology favoring large capital and the consumer appetites of the middle and upper classes, and with the cross-pollination of gritty crime dramas by American and Hong Kong directors, there appeared a number of notable films (especially from directors Ram Gopal Verma and Vishal Bhardwaj) that depicted life in the Mumbai underworld with a new level of naturalism in both mise-en-scene and dialog. Although the trajectory of the protagonists of these films still generally ended in violent death, the plots now assumed an encompassing amorality in which criminal activity paralleled or was barely distinguished from politics, big business, and police work. Identification with gangster heroes, who continued to display such traditional Hindi cinematic ideals as dosti (male friendship) and clan loyalty (here transferred to the surrogate “family” of the mob), permitted filmmakers to explore the fascinating psychology of characters, such as Satya and Bhikhu Mhatre in Verma’s SATYA (1998), whose evident humanity and even charming bonhomie coexisted with a shocking and repellent brutality.

In MAQBOOL, Vishal Bhardwaj tells a very similar story, enacted by a similar set of character types, of the rise and fall of a powerful don. Unlike SATYA’s (largely) Hindu milieu, however, the mob here is predominantly Muslim—a fact that is ostensibly faithful to the demographics of a significant part of the Mumbai underworld—and the mise-en-scene and plot deftly evoke the residue of courtly and feudal tastes and ostentatious but Sufi-flavored piety displayed by its self-made “kings,” as well as their adoration by the city’s Muslim underclass. Against this rich cultural backdrop, the director has cleverly (if somewhat freely) adapted, right from the common Islamic name of its antihero, Shakespeare’s archetypal tale of unchecked ambition and its fateful consequences. Aided by a smart script, restrained pacing, and uniformly remarkable performances from his principals, Bhardwaj has crafted a justly acclaimed film (India Today declared it the best of 2003) that works both as a gangster drama and as a new, and insightful, cultural transposition of and commentary on Macbeth.

The story begins, needless to say, on a stormy night. Shakespeare’s three “weird sisters” are transposed into two thoroughly corrupt but comically bumbling Hindu cops, Purohit and Pandit (Naseeruddin Shah and Om Puri), who dabble in the occult. Even as they assist the criminal gang to which they are beholden in wiping out a rival clan, they detect, via the kundal charts used by Indian astrologers, propitious signs for the potential ascent of its second-in-command, Maqbool (Irfan Khan), to eventually supplant his master, the “king of kings” Jahangir Khan, better known as “Abba-ji” (“revered father,” extraordinarily portrayed by Pankaj Kapoor in a Filmfare Award-winning performance that might be termed Brando-esque were it not so thoroughly steeped in Indo-Muslim mannerisms). The first appearance of the recurring kundal motif, casually traced by Pandit’s finger on the misted windowpane of a van in which he and his buddy interrogate and then dispatch a member of the rival faction, is a brilliant cinematic moment that effectively evokes the theatrical archetype even as it literally etches the ominous and sanguine outline of the ensuing tale.

Macbeth is the shortest by far of Shakespeare’s tragedies, and there has long been scholarly controversy over whether the extant script is complete, and some have even questioned whether its antihero, driven to fateful action by a dormant ambition stirred by the weird sisters’ prophesy and his wife’s prodding, is adequately motivated to betray and murder his master, the old King Duncan. Bharadwaj implicitly enters this debate by giving his Maqbool several additional incitements. The most prominent of these is lust, for Lady Macbeth here is the beautiful Nimmi (Tabu), a prostitute who is initially encountered as the latest in a series of Abba-ji’s mistresses, though it is clear that she has had a past liaison with Maqbool and nurses an ongoing passion for him, which he shares but rigidly suppresses.

She soon provides him with a further motive by revealing that his high position in the gang may be imperiled by the rise of the young Guddu (Ajay Gehi), the son of Maqbool’s Hindu crony (and the film’s Banquo), Kaka (Piyush Mishra). Guddu is carrying on with Abba-ji’s only and adored child, Sameera (Masumi Makhija), and thus (after a marriage that Maqbool dutifully helps broker) threatens to become the kingpin’s male heir—and the film’s Malcolm. Later, Nimmi’s own rejection by Abba-ji, in favor of a slutty film actress from a production company controlled by his mob, provides yet a further motive. (Incidentally, this is one of the film’s several invocations of Bombay filmdom’s much-discussed links with the underworld; in another, Kaka proposes to Abba-ji that they get a film made as a vehicle for Nimmi, and offers him his choice of prominent directors, naming Karan Johar, Subhash Ghai, Ram Gopal Verma, and Mani Ratnam—he modestly omits, of course, Vishal Bharadwaj.)

Despite having so many motives, Maqbool appears deeply conflicted and guilt-ridden, even before the murder, due to Irfan Khan’s consummate acting and the script’s elaborate delineation of his fealty to Abba-ji. Both Khan’s and Kapoor’s low voices and dark, mask-like faces register an extraordinary spectrum of emotional nuance: genuine, assumed, or suppressed, and their complex “father-son” relationship—always overshadowed by its foreordained outcome—is one of the film’s achievements.

Like a number of recent big-budget films that aim to reach both a mass and a “class” (i.e., higher-educated, middle-class) audience, MAQBOOL uses songs sparingly. One is non-diegetic background commentary (Rone do, “Let me cry,” which accompanies Nimmi’s gradual seduction of Maqbool after she reveals the misery of her life with Abba-ji, but the lyrics of which are sung by an unseen female performer), and the other two figure in the narrative at moments when music would realistically occur. Thus Jhin min jhini is sung by women at Sameera’s wedding, and the group dancing that accompanies it is notably unsynchronized. Perhaps the most remarkable song sequence is Ru-ba-ru (“we are face to face”), performed early in the film by qawwals at a Sufi tomb (dargah) visited by Abba-ji’s coterie. Here conventional Sufi-style lyrics about the greatness of love and the unveiling of the Beloved accompany a strikingly-edited “choreography” of glances and gestures by the principals, that reflect both Maqbool’s conflicted reaction to Nimmi’s recent declaration of lust for him, and his growing realization of the upstart Guddu’s risky romance with Abba-ji’s daughter.

Though the ultimate conclusion may be said to be doubly determined (by cinematic convention as much as by theatrical source), the interest, as in many Hindi films that recapitulate well-worn conventions, lies in the twists introduced into the familiar fabric. Here, Maqbool and his Lady’s slowly-consuming guilt over Abba-ji’s bloody murder is compounded by an ill-omened infant of doubtful paternity, and the new don’s downfall involves not only the wrathful sons of his murdered cohorts, but a botched hundred-million-rupee smuggling deal that apparently would have provided arms to terrorists (something to which even Abba-ji had refused to stoop), and a vengeful police inspector banished to the marine patrol by the gangsters’ political allies. Yet the complex, haunted Maqbool remains sympathetic—and almost heroic—to the end.

[The Eagle DVD of MAQBOOL offers a high quality print of the film, and subtitles to both dialog and song lyrics. Chapters are notably few, however (six for the entire film), making it somewhat difficult to quickly locate specific scenes.]