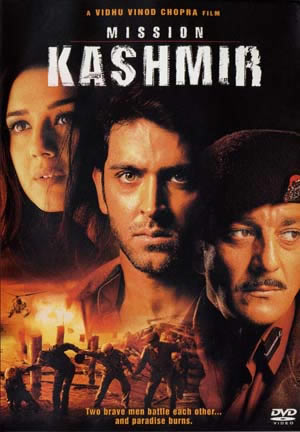

MISSION KASHMIR

2000, Hindi, 155 minutes

Produced and Directed by Vidhu Vinod Chopra

Story by Vidhu Vinod Chopra and Vikram Chandra; Screenplay: Abhijat Joshi, Suketu Mehta, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Vikram Chandra; Dialogs: Atul Tiwari; Art Director: Nitin Chandrakant Desai; Lyrics: Rahat Indori, Sameer; Music: Shankar, Ehsaan, Loy; Cinematography: Binod Pradhan

Hrithik Roshan’s rise to megastardom has been dramatic even by Bollywood standards; he became a household name in India (and for some households, a sort of Great Hindu Hope after a decade dominated by Khans: Salman, Shah Rukh, and Aamir), not to mention its Coca-Cola spokes-deity, on the strength of a single film, KAHO NAA…PYAAR HAI (2000). That stylish flick, albeit a shameless vehicle for him crafted by his father, filmmaker Rakesh Roshan, packed a lot of entertainment muscle through a witty variation on the proverbial double motif, with Hrithik as both a struggling Mumbai pop singer and a rich New Zealand-resident NRI. His assets, which include an angelic face especially adept at conveying innocence, vulnerability, and anguish, paradoxically placed atop a superhero-on-steroids body, seem to have qualified him to sympathetically play a new incarnation of Hindutva’s Other, the Muslim—while still reassuringly remaining his and its (Hindu) Self—in two subsequent films, the bleak FIZA (2000), and MISSION KASHMIR, in both of which he portrays not the Muslim subalterns of Bachchhan’s “angry young man” period, but nice middle-class boys who go astray and become terrorists after traumatic experiences. Here his name is Altaaf.

This disturbing, grotesquely gorgeous, brazenly patriotic spectacle is hence about Hrithik as much as it is about Kashmir—or rather (to invoke Indira Gandhi’s famous election slogan, “Indira is India”) it is about Hrithik as Kashmir—personified and infantilized, as an eleven-year-old victim of trauma who remains locked, ten years later, in a ruthless quest for revenge. Altaaf’s soul is the prize over which two surrogate father figures battle, and the film is also about the actors who play them. Sanjay Dutt is cast as Inayat Khan, Inspector General of Police for Srinagar: a “good” Muslim (which is to say, pious but not especially religious, and fiercely loyal to India), but also someone who goes out of control when provoked—as when he slaughters (when only an SSP) young Altaaf’s entire family while hunting for a terrorist leader; a “mistake” for which he is not called to book but instead is apparently promoted. Like all good Muslims in India, he has to periodically struggle to prove his “loyalty,” which is a blow to his izzat (honor, self-pride), and also an allusion to Dutt’s legendary biography: the bad-boy son of a Hindu father and Muslim mother (Nargis, who was also “Mother India”), he was reputedly involved in drugs and often linked to the Muslim underworld of Mumbai, and was implicated in a series of terrorist bombings in the city in 1993. His character Khan, despite continuing outbursts of loyalty-asserting but patently illegal and counterproductive violence (like summarily executing captives who might reveal the truth about the film’s titular conspiracy, a plot to spark a communal bloodbath by blowing up two sacred sites in Srinagar), is redeemed by his soulful eyes, his love for his devoted Hindu wife Neelima (Sonali Kulkarni), his rakish Harley Davidson jacket, and his own revenge agenda (the couple’s son Irfan died when doctors terrorized by an anti-Indian fatwa refused to treat the child of a police officer). He briefly adopts the traumatized Altaaf, but loses him again when the boy accidentally discovers, in Khan’s desk drawer, the ski-mask worn by the slayer of Altaaf’s family.

Altaaf’s other “father” is the Pathan terrorist Hilal, played (invoking several distasteful Pathan stereotypes) by Jackie Shroff, who is better known for his portrayal of hunky Hindu heroes (e.g., Ram in 1993’s KHALNAYAK, where he was also the nemesis of Dutt as a bad-boy-turned-villain). Hilal is the Bad Muslim, which is to say a fundamentalist and terrorist, an infiltrator from Afghanistan (where he was once tortured by the Soviets), and a Rasputin-like monster who spouts the rhetoric of Allah and jihad while exploiting and sometimes killing his own men. He is, in short, the Problem in Kashmir, in the film’s view, and he takes his orders from a trio of (presumably) Al Qaeda agents in a distant war room, presided over by the silhouetted figure of an Osama bin Laden lookalike.

What all this intertextuality (standard enough in Hindi cinema) means is that the film doesn’t have to waste time on character or motivation, much less on the complexities of Kashmir’s thirty-year-old civil war or its manipulation by generations of Indian and Pakistani politicians. Instead it can concentrate on Feeling and Spectacle—the former weepy and expansive, the latter alternately picture-pretty and explosively violent. Altaaf is given love interest in the form of perky and versatile Sufiya, a.k.a. Sufi (Preity Zinta), another Good Muslim who works for Doordarshan (state TV) in Srinagar, where she is both a news anchorwoman and a song and dance queen. Though she and Altaaf last saw each other as children, their eternal love is instantly renewed when he descends (literally) on Kashmir again, after ten lost years of terrorist training. While plotting to blow up Sufi’s transmission tower, Altaaf takes time out to dance exuberantly in her televised spectacles of National Integration. These might be auto-parody, or just incredibly bad taste: they conjure up a Never-Never-Kashmir, literally Made For (and of) TV, with “lakes” formed of glass blocks that resemble sets, upon which colorfully-costumed “natives” sing souped-up Kashmiri folksongs about bumble bees and communal harmony, with all the enthusiasm of, say, Chinese extras in a Beijing musical about life in Lhasa…. To be fair, the film makes brief, sporadic efforts to complicate its own picture: its secessionist militants are sympathetically shown as good-natured, tea-drinking boys who have simply fallen into Bad (Islamic fundamentalist) Company—though this furthers the depiction of Muslims as errant children who need to be straightened out. To balance this, we momentarily hear the vengeful rhetoric of a Kashmiri pandit policeman talking about brahmans having to flee their ancestral homes; he is then chastened by a Sikh comrade who lost his family in the New Delhi pogroms of 1984—suggesting that everyone has suffered and everyone must forgive (though this begs the question of why minorities suffer and have to forgive more).

At the risk of stating the obvious, although the movie preaches against violence, it is permeated with its elegantly choreographed portrayal, displaying great technical finesse, with incessant slow-mo sequences of kung-fu combat, shattering glass and splintering wood, and massive red-orange explosions (incidentally, the opening credits, featuring an exploding shikhara or boat-taxi against which the titles literally go up in smoke, is especially impressive). But whereas such sights in a standard masala film occur in a cinematic fantasy realm, these are set in an actual war zone: the real Srinagar that we voyeuristically see (with the cooperation of Farooq Abdullah’s government and, one assumes, platoons of protective forces for the filmcrew), where real buildings lie in ruins and where real people die violent deaths almost daily.

But as is commonplace in Hindi cinema (and Hindu mythology), in the end, all problems, cosmic and national, come down to family spats, with men battling it out while women keep the flame of faith and unconditional love burning. Though he had to die for his crimes in FIZA, Hrithik/Altaaf is redeemed here when he finally learns to Just Say No to Hilal’s message of hate, and to love his Big Father (Dutt’s violent but basically “good” Father India). Reborn after a purifyingdubki (immersion) in Dal Lake, his boyish dreams are no longer of unavenged massacres, but of (what else?) an Astroturf cricket pitch. Itself a Great Indian Metaphor—that other, less-sanguine battlefield for Indo-Pak rivalries, and lately for the revision of colonial history (in LAGAAN)—here, it is especially a Field of Dreams where flawed fathers and straying sons are reunited in good, clean, nationalistic family fun.

[The DVD of MISSION KASHMIR is distributed by Sony and is of excellent quality. Subtitles are available for songs as well as dialog. This is of course a welcome feature, as is the fact that—due to its distribution—it is turning up at Blockbuster outlets. The shape of things to come?]