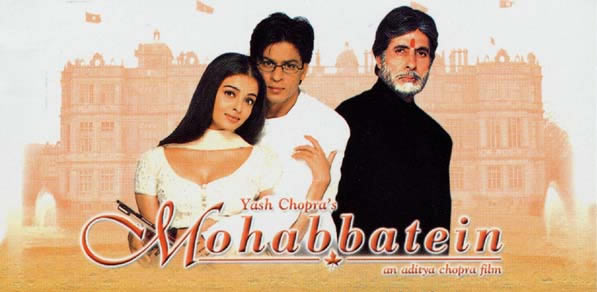

MOHABBATEIN

(“Love Stories,” 2001, Hindi, 216 minutes)

Produced by Yash Chopra

Directed by Aditya Chopra

Story, screenplay and dialogues: Aditya Chopra; Lyrics: Anand Bakshi; Music: Jatin – Lalit; Cinematography: Manmohan Singh

The House of Chopra is understandably keen to repeat the phenomenal success of 1997’s DIL TO PAGAL HAI, but despite aggressively pushing most of the same buttons – thin, elemental plot awash in romanticism and set in a yuppie never-never land, mega stars, lavish sets and production numbers, and a catchy score – none of its recent efforts (cf. KABHI KHUSHI KABHIE GHAM) is up to the exuberant pointlessness of the earlier film. MOHABBATEIN is ostensibly a parable of the eternal conflict between Love and Duty, set in an elite boarding school for junior-college age boys (“college,” in the Indian system, though the subtitles regularly refer to the institution as a “University”). The headmaster (and one of the few visible employees) is the ultra-strict Mr. Narayan Shankar (Amitabh Bachchan), and his code of “tradition, honor, discipline” is to be rigidly maintained on threat of expulsion – which, for reasons never explained, will insure permanent blacklisting by every other school in the land. Yet three new students, Vicky, Karan, and Sameer (played by newcomers Uday Chopra, Jimmy Shergill, and Jugal Hansraj), roommates all, long to fall in love – an especial taboo, as it is rumored that the one student who historically did so, and with the headmaster’s daughter no less, was indeed expelled; moreover, the girl then committed suicide. Fortunately, along comes Raj Ayan (Shah Rukh Khan), a flower-powered violinist and music teacher. Though music has always been banned from the curriculum, Mr. Shankar unaccountably hires Raj on a one-year, non-cancellable contract, and Raj proceeds to encourage the schoolboys, but mainly our three focus-boys, to dream impossible dreams of love with three sweet young things: Ishika (Shamita Shetty), a haughty student at an adjacent girl’s college, Kiran (Preeti Jhangiani) the widow of an air force officer who was lost on the border soon after their wedding, but whose death is denied by the girl’s dour father-in-law (played by Amrish Puri, naturally), and Sanjana (Kim Sharma), a local girl who is already engaged to a mega-rich playboy. A long flashback will add the love story of Raj (who is actually Raj A. Malhotra, the famously-expelled student, who the headmaster never actually saw) and Megha, the headmaster’s dead daughter (Aishwarya Rai), and then there is a comic love-track featuring two local merchants Kake (Anupam Kher) and Preeto (Archana Puran Singh), who rehearse all the stereotypes of Punjabi Sikh earthiness and buffoonery. These love tales unfold amidst much singing and spectacular choreography, punctuated by slow verbal duels between the glowering Shankar and puckish Raj, over just whose Will will be done.

It all sounds complex, but it really isn’t, especially since you have (if you choose) 3 hours and 36 minutes to sort it out. This is not a film that encourages thinking about the various gaping holes in its plot (Why does Shankar hire Raj on a non-cancellable contract? Why are the school’s vaunted rules so easily broken without penalty? Why do three roommates, among several hundred boys, fall in love? Why are there no apparent classes, books or exams? Why is Megha so happy about killing herself? How does Karan master the piano in a matter of days? etc., etc.). It is more interesting to try to sort out the hybrid iconography and cultural resonances of the film’s surreal fantasy world. The school is called “Gurukul” (Sanskrit for “house of the teacher” and a label used for the boys’ schools run, since the late 19th century, by the Vedic revivalist sect Arya Samaj), and Mr. Shankar, wrapped in costly shawls, greets the sunrise daily (surya-namaskar) and conducts Vedic fire rituals amid his white-clad charges before an austere and immaculate Shiva temple (which Raj, in an allusion to Chopra’s early Bachchan film DEEWAR, refuses to enter for most of the movie – Amitabh’s Vijay once did the same, and the gesture now underscores superstar Khan’s assumption – both as actor and character – of the role of Bachchan’s symbolic son). Gurukul is ostensibly located somewhere in India, yet it is patently a magnificent British country estate (Longleat House, Wiltshire), with some background hills superimposed; its classic Georgian architecture opens to reveal wood-paneled suites and an echoing Romanesque great hall in which the boys regularly assemble to witness the Triumph of the (headmaster’s) Will. The adjacent “town” suggests the Disney Epcot version of an Indian hill station, with pastel buildings and well-scrubbed shops and locals. Gurukul’s sister institution is a “convent school” run by prim Miss Monica (played by Helen – the onetime cabaret queen suffers such roles nowadays), who has a painting of the Blessed Virgin in her office; yet the girls wear the skimpiest of negligés and cavort in a gym adorned with murals of naked nymphs – and yes, Miss Monica gets to strut her stuff eventually, too.

Apart from intertextual and transnational fun, does it all mean anything? In the disorderly ambience of Indian middle class life, the ideal of male “discipline” – associated with the army and elite boarding schools, both inherited from the British – looms large; here it is further equated with upper-caste neo-Hinduism (reduced to a few elemental symbols and gestures), industrial-strength patriarchy, and the “fear” necessary to insure obedience to Authority (Shankar twice intones, “In the battle between love and fear, fear always triumphs”). The obverse of this ideological complex is passionate love (mohabbat, pyaar) which here connotes not only romance but also individualism, (male) agency, art, and general joie de vivre. Since it is hard to buy into the notion that the school actually embodies “discipline” (every stated rule is easily broken) or that the film’s attractive young mannequins actually “love” each other in any mature sense, both categories fairly evaporate under the ideological burden they carry, leaving the elemental “father” – “son” chess match which is at the film’s core (with the ghostly daughter as its pawn and queen), and which can only end in a carefully-staged draw. Bachchan and Khan both look as monumental as the buildings, and do the best that can be expected under the circumstances.

The six songs are uniformly catchy (especially Kyaa yehi pyaar hai, "Is this love?") and the slick production numbers are what one has come to expect of late: massive ensemble spectacles coded to various consumer subcastes – one in globalized spandex, one in deshi raw silk, etc.

[The Yash Raj Films double-DVD set is of high quality, with songs subtitled, and includes, for real martyrs, hours of “the making of” interviews and additional scenes they just couldn’t squeeze in.]