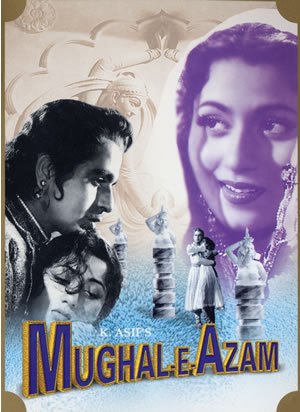

MUGHAL-E-AZAM ("The Great Mughal")

1960, Hindi, 198 minutes.

Produced and Directed by K. Asif

Cinematography: R. D. Mathur; Dialogs: Aman, Kamal Amrohi, Ehsan Rizvi, Wajahat Mirza; Music: Naushad; Lyrics: Shakeel Badaiyuni; Dance Director: Lachchu Maharaj

The theme of the conflict between passionate individual love (pyar, mohabbat) and duty—especially the duty owed to one's father and patriarchal family lineage (involving the obligation to maintain izzat or "honor," maryada, "propriety," and usool, "principles") may be to mainstream Hindi filmmaking what "boy meets girl" was to Samuel Goldwyn's Hollywood—an abiding preoccupation that spawns endless cinematic permutations. Yet for sheer baroque grandiosity, K. Asif's excessive elaboration of the theme remains in a class by itself, and more than forty years after its release, still holds a place on nearly every list of the "ten best Hindi films of all time." Purportedly a decade in the making, it was said to have been the costliest film yet produced in India. It's not hard to see why. Asif's grand operatic vision piles spectacle on spectacle, moving masses of extras with a choreography reminiscent of Fritz Lang or Sergei Eisenstein, and fabricating fairtytale sets that have definitively stamped popular imaginings of Mughal imperial opulence. Asif's ultimate trump card was technicolor—then prohibitively expensive for Indian filmmakers, and so reserved by the director for two legendary climactic musical scenes, both set in the royal pleasure pavilion or Shish Mahal ("palace of mirrors," stunningly crafted by mirrorwork master Agha Shirazi), that unfold as mind-blowing epiphanies.

The simple storyline blends facts of history—the sometimes tumultuous relationship between the Mughal empire's most charismatic ruler, Akbar the Great (1542-1605), and his eldest son and designated heir Prince Salim (later the Emperor Jahangir, 1569-1627), a far weaker character with a well-attested taste for wine, women, and opium—with the popular story of the slave girl and court dancer Anarkali ("pomegranate blossom"), for whose sake Salim is supposed to have defied his father, and whose legendary fate was to be walled-up alive at Akbar's order. In the role of Akbar, Prithviraj Kapoor gives his quintessential performance as outwardly-stern-but-inwardly-suffering patriarch (cf. Judge Raghunath in AWARA), declaiming every line (composed in an Urdu so thickly Persianized one could weave rugs out of it) in a stentorian baritone that even Amitabh Bachchan might envy. As the film opens, Akbar, long childless despite his ample harem (containing many Hindu princesses acquired through marital alliances with feudatory Rajput kingdoms), petitions the Sufi saint Salim Chishti for a son; the murmured prayers of the "friend of God" fade into rejoicing in the palace over the birth of an heir, named for the saint, to Joda Bai (Durga Khote), Akbar's principal queen. But the young prince, reared amidst bevies of doting slave girls (with a cameo by Johnny Walker as a transvestite eunuch) soon proves to be anything but saintly. When Akbar finds him collapsed in a drunken stupor, he packs the lad off to the front lines of the ever-expanding Empire, under the care of trusted general Man Singh, for a little toughening up—fourteen years worth. War works wonders; the chastened, grown-up Salim (Dilip Kumar) becomes a military hero, sending home versified reports penned in his own blood. Eventually, even Akbar is satisfied and calls him back. The matronly Joda Bai, who has been fervently praying to Lord Krishna for her son's return, gives Salim a maternal welcome that stops just short of suckling him. Salim soon dons bejeweled slippers and, with apparently equal ease, slips back into the sybaritic lifestyle of the court. Enter Bahar ("springtime," Nigar Sultana), an ambitious lady-in-waiting who aspires to the rank of empress (a possible allusion to the ruthless Persian princess Nur Jahan, who would eventually dominate the historical Jahangir's life). Seeking to ingratiate herself with Salim, she hires a moody sculptor (Kumar) to create a statue embodying eros. He takes as his model a palace slave-girl, Nadira (Madhubala), whose impersonation of the still-uncompleted statue steals Salim's heart. It charms the emperor as well, who renames her "Anarkali" and promotes her to the queen mother's service. Anarkali likewise falls in love with Salim and the latter soon vows to make her his future Empress, against her own and his father's wishes. The rest of the film (and there is plenty more!) milks this scenario—two strong-willed males battling over honor and authority, with one beautiful woman as the stake and another as scheming nemesis—for every conceivable drop of blood and pathos.

There is eroticism aplenty, albeit often veiled and fetishistic: as when Anarkali (twice) writhes in chains in Akbar's darkest dungeon under the gaze of black-clad guards, or the moonlit lovescene in which Salim slowly fondles her ecstatic face with an ostrich feather. There are splendid musical numbers, including a poetic duel over the nature of love by two female choruses, stunning kathak dances set in the Shish Mahal, Anarkali's immortal song of defiance of the Emperor, Pyaar kiya to darna kya? ("If you've fallen in love, what is there to fear?"), and the rousing Zindabaad ("Long live love!"), sung by the sculptor and a massed male chorus as Salim is prepared for (apparent) execution for defying his father. There is a colossal battle scene that set a new standard in military spectacle and pyrotechnic effects. There are dazzling operatic sets (erected on sometimes all-too-evident soundstages) that evoke less the rugged architecture left by Akbar (e.g., at Fatehpur Sikri) than the infinite geometries and aquatic fantasies of the more decadent emperors who succeeded him, especially Jahangir's son Shah Jahan, creator of the Taj Mahal. And there is the Artist, embodied in the nameless sculptor clad in a monk-like robe and credited with a series of realistic 3/4 bas reliefs that resemble nothing in historical Mughal art, but suggest the humanism and romanticism that he (and the filmmaker) champions. Their creator is portrayed as a fearless solitary genius, beholden to his royal patrons, yet not afraid to confront them with unpleasant Truth (e.g., in a frieze of a political execution), though the principal outlet for individual expression and dissent in his world remains passionate Love. This is embodied in Anarkali herself, who literally brings to life his plastic vision and whose incandescent portrayal by Madhubala upstages both of the bombastic male leads.

And finally, there is—and not at all subtly—politics. Here the film addresses several agendas. Akbar's reign has sometimes been viewed (especially by British historians) as the highwater mark of Hindu-Muslim amity and state-level collaboration, but the liberal-minded emperor has also been castigated by Hindu nationalists as a wolf in sheep's clothing, who abolished the jizya and pilgrimage taxes in order to weaken Hindu resistance, and who co-opted Rajputs into his service even as he drew their daughters into his overpopulated harem. As a Muslim director negotiating the tricky communal terrain of post-Partition Bombay, Asif is clearly concerned to re-establish Akbar as an exemplary secular nationalist. Much is made of his participation in Hindu rituals with Joda Bai and his close reliance on Rajput ministers (all well attested in the annals of the period), but the director's principal means to his end is to transpose the family onto the nation, with Akbar-the-wounded-patriarch portrayed as a suffering Father India, whose every speech suggests his willingness to sacrifice his personal desires and even his own son for "the people of Hindustan." The Nation looms large throughout, and literally so in the opening and closing segments, when viewers are addressed by an enormous relief map that announces (in a male voice), "I am Hindustan," and proclaims Akbar to have been one of his greatest devotees.

Yet despite the equally portentous presence in several scenes of a giant scale of justice, the audience surely realizes that the decrees of absolutist authority—in the nation as in the family—are not always just. Thus Akbar's unrelenting persecution of Anarkali—his constant denigration of her as a social-climbing slut, for example—contradicts what the audience knows about her purity of heart and lack of ambition. So Salim gets to deliver resounding speeches decrying him as a tyrant and oppressor—though here the context appears squarely and safely personal and domestic: a son's righteous railing at a father's tyranny over his heart and his matrimonial options. Given Asif's agendas, as well as the fact that history records that Salim did not marry someone named Anarkali and preserves the popular legend of her execution, the filmmaker must ultimately give victory to the Father, even bringing the effusive Mother on board for good measure—though he manages a face-saving final twist to leave viewers with a taste of what might be called Compassionate Paternalism. In 1960, this may still have been what many Indians saw the State as potentially providing. But their other parting image is of Anarkali's devastated face—a reminder, perhaps, of the price that is inevitably paid, by some, for the preservation of patriarchal usool.