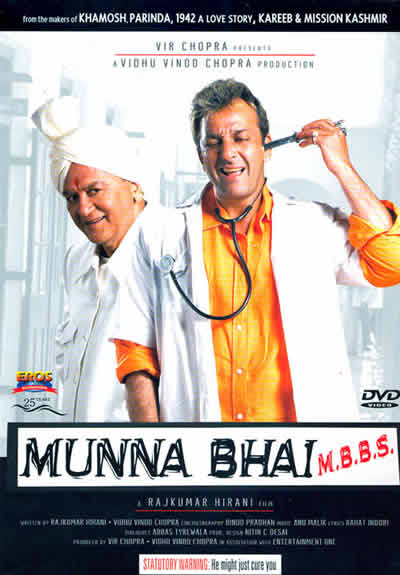

MUNNA BHAI M.B.B.S.

(2003, Hindi, approx. 156 minutes)

Directed by Rajkumar Hirani

Produced by Vidhu Vinod Chopra

Story: Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Rajkumar Hirani, Lajan Joseph; Screenplay: Abbas Tyrewala; Lyrics: Rahat Indori, Abbas Tyrewala; Music: Anu Malik; Cinematography: Binod Pradhan

Although full-length comedies (as opposed to omnibus “social” films with one or more comic subplots) have been a relative rarity in Bombay cinema (for examples, see PADOSAN, 1968, and BAWARCHI, 1972; both comparatively low-budget films aimed at more select “middle-class” audiences), this exuberant farce was a sufficient mainstream hit (plus garnering four Filmfare Awards) that it eventually birthed an even more acclaimed 2006 sequel charting the further adventures of its eponymous hero (a third film was in development in 2007). Following a spate of grim and comparatively “realist” films about the Bombay underworld (e.g., SATYA, 1998; MAQBOOL, 2003), MUNNA BHAI offered, as antidote, the surreal hijinks of a band of lovable thugs whose leader is a veritable avatar of Hindi cinema’s most vaunted character trait: dil (“heart”). Although this “kid” (a free translation of the diminutive and folksy munnaa)—improbably yet appropriately played by the aging “bad boy” of Bombay cinema, Sanjay Dutt—is identified as a gang-leading bhai (literally “brother”), his criminal activities are quickly downplayed (an opening kidnap sequence ends with him releasing the intended victim and instead victimizing the instigator, on discovering that the latter had lied about money) to allow him free reign to take on, with infectious Love (and a little cheating), the pretentious authorities of this world—here represented by the medical establishment of an uncommonly tidy teaching hospital.

|

Munna Bhai is the nickname of Murli Prasad Sharma (Sanjay Dutt), a tapori or “hoodlum,” who, aided by his ever-resourceful lieutenant Sirkishwar, a.k.a. “Circuit” (Arshad Warsi), heads a gang of petty thugs and extortionists. We soon learn, however, that despite being “king” of the washerman’s neighborhood in which he resides, Munna lives in fear and awe of his respectable village-based parents, Hari Prasad and Parvati Sharma (Sunil Dutt and Rohini Hatangadi), for whose benefit he has spun a long-running fib about having earned an M.B.B.S. degree (a serviceable “undergraduate” medical certification, though less prestigious than an M.D.).

Whenever the old folks come to visit Bombay, he and his minions stage an elaborate charade, converting their gang lair into the “Shri Hari Prasad Sharma Charitable Hospital”—a ruse finally exposed through the ill-will of Dr. J. C. Asthana (Boman Irani), an old friend of Hari Prasad, whom the latter approaches to arrange a marriage between Murali/Munna and Asthana’s doctor daughter Suman, nicknamed “Chinki” (Gracy Singh).

When Sharma senior heads home, humiliated, heartbroken, and furious, the disgraced Munna sets out to redeem himself by earning both the degree and the girl. Cheating his way into the “Imperial Institute of Medical Sciences,” he has to contend with such obstacles as ragging upperclassmen and stomach-turning anatomy lessons, not to mention the discovery that the inimical Dr. Asthana is Dean.

When strongarm tactics fail, Munna, under imminent threat of being “rusticated” (expelled), has recourse to charm, verbal wit, and (his ultimate weapon, it turns out) the “magic hug” (jaadu ki jhappi) favored by his loving Mom. Of course, the film’s principal flavor of haasya rasa(the comic mood) is tempered, for a balance of masalas, by modest helpings of pathos (karunaa rasa) in the form of tearjerker subplots about a handsome young man (Jimmy Shergill) dying of stomach cancer, a paralyzed Bengali gentleman who has been declared “brain-dead” (Yatin Karyekar), and (this being Mumbai) a carom-obsessed Parsi codger who is at death’s door. Needless to say, the irrepressible Munna has some ilaaj (medicine) for all of them. |

|

|

|

Two extra-filmic narratives are relevant to MUNNA BHAI’s great success. The first is the checkered career of Sanjay Dutt, the son born of Sunil Dutt’s “scandalous” (but celebrated) marriage to the Muslim actress Nargis, after she played his own (and everyone else’s) mom in MOTHER INDIA. Following an adolescence marred by substance abuse (that reputedly broke Nargis’ heart even as she was fighting the cancer that eventually killed her), Dutt became a successful actor known for violent and “macho” roles that made him a special favorite, in the post-Bachchan era, of the urban proletariat.

This fan base did not desert him even when Dutt was arrested and jailed for eighteen months for alleged connections with the Muslim dons blamed for the 1993 bomb blasts that claimed more than 250 lives in Mumbai. Dutt’s penchant for amassing illegal weapons and his rumored collusion with terrorists (though the latter charge was eventually dismissed in court) reportedly weighted heavily on his aging father, who had won a seat in Parliament in 1984 and eventually became a Cabinet Minister.

The latter’s return from a long cinematic retirement to play Munna’s fictive father in the film—a father who initially disapproves of his son’s lifestyle but is eventually won over by his heroic capacity to love—was thus popularly savored as the filmi transposition of an off-screen reconciliation, that acquired still more poignancy following the senior Dutt’s death (this was his last film) in 2005. |

|

The film’s second implicit narrative is more subtle, though (in my view) equally important. In downplaying Munna’s violent and dishonest propensities and emphasizing his empathic dil, the film elevates the fast-talking, streetsmart tapori to the status of middle class icon, or, more precisely, icon for new aspirants to middle class status. It thus depicts the triumph of a transgressive “upstart” straining toward social respectability—here represented by an eminently respectable profession—and achieving it through mockery and subversion of the already-arrived “old middle class,” the group represented by Dr. Asthana in the film (note that his name suggests a fixed “station” or sthaan). These competing class identities, ludically enacted through costume and body language as well as the basic storyline, are also linguistically coded in the speech of the principals. For although Asthana code-switches between Hindi and English, his frequent use of the latter favors complete sentences and hence suggests fluency in the elite, “father tongue” of the urban establishment. In contrast, Munna’s linguistic base is an updated version of pungent Mumbaiyya dialect—a mixture of Hindi, other Indian languages, and English, considered substandard to school-taught khari boli Hindi but long popularized by the tapori heroes portrayed by Amitabh Bachchan and Aamir Khan, and here further spiced with “Hinglish” words and phrases absorbed from contemporary mass media (and, indeed, proliferated further by the film itself: e.g. Munna’s constant use of “No tension!” to mean “Relax,” “Calm down,” “Take it easy,” etc.). Tellingly, the only occasion on which Munna pronounces complete English sentences is when parroting responses he has crammed for a medical school examination—though these mantras quickly give way, under emotional pressure, to his characteristic patois. And, like the class to which he belongs, Munna’s idea of recreational “culture” is heavily infuenced by Hindi cinema—as reflected in the elaborate and tacky “cabaret” scene he stages on the hospital ward to cheer up his dying friend Zaheer (the song Sikh le, “Learn [to live before you die]”)—a harmless if risqué entertainment that naturally enrages the stuffed-shirt Asthana, who preaches a dispassionate and “rational” brand of medicine, and who regularly suppresses his rage through manic bouts of “laughter therapy.” But, in the end, it is of course the vulgar but impassioned nouveau arrivé who arrives, acquires love and respect (and a clinic!), and gets the last laugh. |

|

[The Eros DVD of MUNNA BHAI M.B.B.S. is of good image and sound quality and includes a “Making of” feature. Subtitles, provided for the entire film (songs included), are likewise of unusually good quality, and seem, for a change, to have been thoughtfully done. The choice of rendering Munna and his friends’ dialect through current American slang is generally effective.]