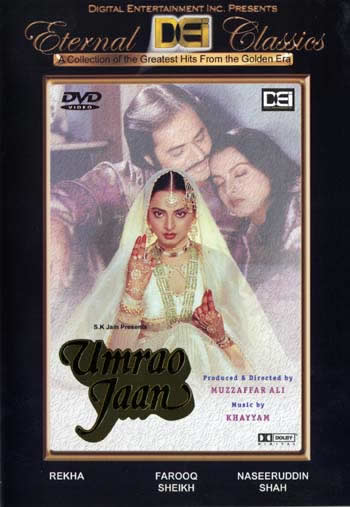

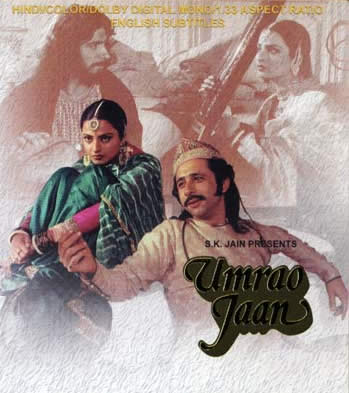

UMRAO JAAN

1981, Hindi, 145 minutes

Produced and Directed by Muzaffar Ali

Based on the novel by Mirza Muhammad Hadi Ruswa

Screenplay and dialogue: Shama Zaidi, Javed Siddiqui, Muzaffar Ali; Lyrics: Shahryar; Music: Khayyam

Choreography: Kumudini Lakhia, Gopi Krishna; Cameraman: Pravin Bhatt

Muzaffar Ali’s adaptation of the first great modern Urdu novel, Umrao Jan Ada by Mirza Ruswa (1905), makes cinematic adjustments and compromises, but is a gem all the same. Whereas Ruswa interwove his fictional memoir of a 19th century tawayaf (courtesan or public woman) of Lucknow with a lively dialogic frame-narrative, in which the courtesan and author, both grown old, reminisce, tease one another, and quote copious ghazal poetry, the director presents a linear account of Umrao’s early life from childhood on, ending soon after the Rebellion of 1857 (a.k.a., the “Sepoy Mutiny”). Where the novel’s heroine is said to be plain, though blessed with a good voice and sharp mind, the film’s is…well, Rekha, here further endowed with the voice of Asha Bhosle singing ghazals that have all become famous. Where the literary Umrao admits to “never having really loved a man,” the cinematic Umrao has one great and lingering romance. The chronology of events is drastically altered as well, and of course a great deal is omitted. Nevertheless, Ali’s film is lovely in its own right, and apart from offering fine performances by renowned actors and gorgeous songs and dances, it succeeds remarkably well in capturing (through lovely cinematography and accurate period sets) much of the atmosphere of the novel, which both celebrates and problematizes the world of the chowk—the prostitute’s quarter of old Lucknow. It also conveys some of Ruswa’s surprisingly radical subtext: his meditation on the plight of upper-class women, whether begums (respectable but housebound wives) or tawayafs (alluring and educated but socially-disapproved courtesans), as birds equally caged by patriarchal double standards. It thus invites comparison with Kamal Amrohi’s PAKEEZAH (1971), which explores some of the same themes in a more allegorical register.

The setting is Lucknow, capital of the northeastern kingdom of Oudh (a.k.a. Awadh), which broke away from the crumbling Mughal Empire in the mid-eighteenth century. After the cultural and economic decline of Delhi, many poets and artists moved eastward, seeking the patronage of the heterodox Shi’ite Muslim rulers of Oudh. Their capital became renowned for the refinement and exaggerated elegance of its Persianized Urdu, as well as for the decadence of its lifestyle, which revolved around the Nawab’s court and the prostitutes’ chowk. The British East India Company’s forceful annexation of Oudh and deposition of its last king in 1856 helped to precipitate the outbreak, the following year, of widespread rebellion against their rule.

As the credits roll, we see the child Ameeran (Umme Farwa), a middle-class Muslim girl of Faizabad, being adorned, at roughly age twelve, for her engagement ceremony while women sing a traditional song. We soon learn that a neighbor of the family, Dilawar Khan, has a grudge against Ameeran’s father (whose testimony in a court case once sent him to prison); the vengeful Khan lures Ameeran from her house, then abducts her at knifepoint. Though he plans to kill her, a companion proposes instead taking her to Lucknow and selling her. After spending several days with a family who deal in stolen children, Ameeran and another frightened girl, Ram Dei, are both sold—the latter to a wealthy family (in the novel we learn that she is meant to be a sex-education toy for a young nawab or aristocrat). As the less attractive of the two, Ameeran is taken to Lucknow and sold to Madame Khanum (Shaukat Kaifi), the keeper of a high-class brothel where dandified gentlemen, wrapped in costly brocaded shawls and fortified by tobacco and opium, pass their evenings engaging in (for starters) witty conversation, musical recitals, and the chewing of paan (a mildly-addictive spiced betel preparation). But to the child, whom Khanum promptly renames Umrao and who understands nothing of the brothel’s commodity culture, it seems a magical and luxurious place, especially after her horrific ordeal. She has no hope of returning to her family (many days journey away) and is “adopted” by kindly Auntie Husaini (Dina Pathak), Khanum’s matronly servant.

Soon she begins her schooling in music, dance, and poetry—a world of art and learning that would have been barred to her had she remained with her family. As she and Khanum’s own daughter Bismillah practice their kathak dance, they are transformed into beautiful young women (Rekha and Prema Narayan). Umrao soon acquires an in-house paramour in the mischievous Gauhar Mirza (Naseeruddin Shah), the son of a prostitute and himself a sometime pimp. She also acquires a poetry teacher, Maulvi Saheb (Gajanan Jagirdar), who is also Hussaini’s lover. Once she begins performing (represented by the ghazal“Dil cheez kya hai” (“Never mind my heart, take my life”) she attracts the attention of a dashing and cultured young nawab, Sultan Sahab (Farouque Shaikh), who shares her taste for poetry. Several scenes are wonderfully evocative of the poetry-smitten world of 19th century Islamicate urban culture, in which all educated people were aspiring Urdu poets, and evenings were spent in mehfils or poetic gatherings at which a candle was passed around the room, and each person before whom it rested had to recite a poem, ideally of his own composition. The performances of ghazals attributed to Umrao Jaan (who composed under the pen-name “Ada”—“the flirtatious one”—which was artfully worked into the final or “signature” couplet of each poem) are likewise memorable (e.g., the haunting "In aankhon ki masti," “The intoxication of these eyes”). Although Rekha lacks the grace of a classically-trained dancer, the music and opulent mise-en-scene (not to mention her intoxicating eyes) more than compensate.

Umrao’s romantic idyll with Nawab Sultan occupies much more of the film than it does of the novel, but in both it is repeatedly frustrated by a series of misfortunes that remind her of her status as a public woman who can never truly claim a man. These blows fall thick and fast after Intermission, and as a result the film gets a bit confusing. Frustrated in her love for Sultan (who is shortly to be married) and sick of her madam’s greed, Umrao decides to flee Khanum’s establishment with a darkly handsome admirer (Raj Babbar) who proves to be one Faiz Ali, a notorious daku or highwayman. When he is slain by rural police, Umrao makes her way to the commercial town of Kanpur and briefly (though in fact this compresses several years) sets up on her own, performing for the appreciative provincial gentry. This leads to an engagement at the home of a wealthy begum who proves to be none other than Ram Dei, the Hindu girl who was kidnapped and sold at the same time as Ameeran—by a quirk of fate, she has become the legal wife of a certain powerful Nawab. Discovered by Husaini and Gauhar Mirza, Umrao is brought back to her “home” in Lucknow, where Mirza (at Khanum’s urging, to prevent any future escape) harasses her with a lawsuit alleging that she married him. Just then the Rebellion breaks out, the British lay siege to Lucknow, and amid much confusion the denizens of the chowk escape the city. When the refugees pause overnight in Faizabad, Umrao again slips away from Khanum and eventually (more compression here) takes a flat in the very town in which she was born. Here too she receives invitations to perform in private homes, and the strange familiarity of one of these elicits the beautiful ghazal “Yeh kya jagah hai doston” (“What place is this, friends?”), that leads to a heartrending reunion.

Despite its uneven and sometimes confusing pace—familiarity with the novel (which is readily available in translation; see below), and with a bit of North Indian history certainly helps—this film gets high marks for its strong cast, beautifully written screenplay, and wonderful atmospherics. The exquisite locations never look like sets, and the shimmering costumes (of dazzling brocade and gauziest muslin) seem to be the work of master weavers. The beautiful songs are accompanied by traditional instruments (such as the plaintive-voiced sarangi) appropriate to the period. The director’s loving attention to visual detail is constantly evident, in carpets, hookahs, silver paan boxes, crystal lamps, and the Vermeer-like mirrors that confront the melancholy Umrao at every turn in her eventful journey.

[Two DVDs of UMARAO JAAN are on the market. That from Media Digital Entertainment is of very poor quality and should be avoided. The one released by Digital Entertainment Incorporated (DEI) is of excellent quality and its songs are helpfully subtitled too—though Urdu ghazals fare badly in translation. The novel—which is a fine read as well as a helpful guide to this cinematic adaptation—is available in a charming translation by Khushwant Singh and M. A. Husaini under the title Umrao Jan Ada; published in India and still in print (Hyderabad: Disha Books, 1993), it may be ordered from US-based South Asia Books (sabooks@juno.com); I much prefer this translation to the more recent one by David Matthews (Calcutta: Rupa & Co., 1996).]