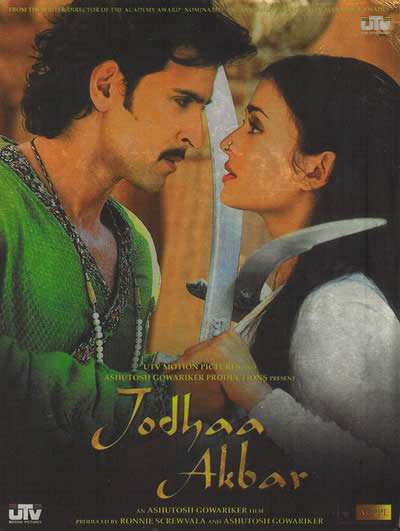

JODHAA AKBAR

(Hindi, 2008, 209 minutes)

Directed by Ashutosh Gowariker

Produced by Ronnie Screwvala and Ashutosh Gowariker

Story: Haidar Ali; screenplay: Haidar Ali and Ashutosh Gowariker; dialogues: K. P. Saxena; lyrics: Javed Akhtar; music: A. R. Rahman; cinematography: Kiiran Deohans; production design: Nitin Chandrakant Desai; costume design: Neeta Lulla

Ashutosh Gowariker’s sumptuous tribute to the Mughal Empire at the height of its culturally-syncretic glory unfolds with the leisurely gait of an imperial elephant. In the grand tradition of Indian (and Bombay cinematic) storytellers, Gowariker is unwilling to send anyone home in under three-plus hours; his remarkable debut film, LAGAAN, acclaimed as a revival of the rarely-made genre of the “historical,” was a tautly-paced underdog sports saga set in the colonial period that kept viewers on the edge of their seats for nearly four. More truly “historical” in subject matter but far looser in plot, JODHAA AKBAR is an essentially atmospheric experience of breathtaking cinematography and mise-en-scène, lovely A. R. Rahman music, unexpectedly strong performances, and an obvious but unobjectionable didactic message (the promotion of inter-religious tolerance, especially between Hindus and Muslims). The best approach to it (now that it’s out on DVD, with its long halves neatly divided between two disks) is to find a comfortable couch on an unhurried evening (or two) and just let it wash over you. It’s a bit like taking a vacation in 16th century North India, without the risk of contracting plague or being decapitated by a warlord.

Anyone who has visited Akbar-period sites such as Agra’s Red Fort or the ghost capital of Fatehpur Sikri will surely relish the astonishing re-imaginings of what these complexes may have looked like when fully outfitted and inhabited. The dramatic hilltop palace of Amer (a.k.a. Amber) and its adjacent ravine appears starkly outlined and reforested, minus the curio shops, buses, touts, and general urban sprawl familiar to today’s Jaipur tourists—a wondrous feat of digital demolition.

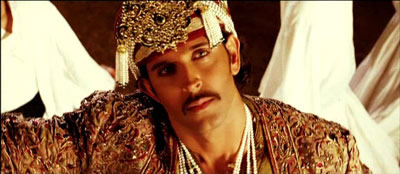

Indeed, everything about the movie is gorgeously beautiful, beginning with the principal players, and (though the storyline takes arguable liberties with known history) production values are sky-high and obvious visual anachronisms relatively few—the most striking perhaps being Jodhaa’s Krishna statuette, which looks like a 19th-century German porcelain rather than the big-eyed, black stone murtis typical of the Mughal period. Other influences may include Chinese historical and martial-arts films, as reflected in a well-choreographed his-and-her sword duel that seems indebted to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. This is also, in a way, a “consumerist” film that continues the pattern of display of conspicuous goodies established by middle-class blockbusters like HUM AAPKE HAIN KOUN and DIL CHAHTA HAI, though here with an “ethno-historic” sensibility: Jodhaa’s lacquered boudoir and Akbar’s jewel-encrusted outfits set a new standard in desi chic. There are acres of glittering fabrics, Persianate gardens aflutter with pigeons and doves, and even a mouthwatering multicourse meal that should send you running to the nearest tandoori-joint buffet.

Don’t expect much suspense, though. The most dramatic thing that happens—Akbar’s temporary exile of his bride on the suspicion that she is betraying him, which occurs just before Interval—is cleared up within fifteen minutes of the film’s resumption, and we again settle back into what is essentially a pleasantly protracted coming-of-age story, albeit its subject is a singularly remarkable pre-modern ruler. With the exception of a brief prologue, most of the action unfolds between 1562 and 1563, the period that saw the twenty-year-old Akbar (who ascended the throne at age fourteen on his father Humayun’s death, but was initially overshadowed by a regent) asserting his own personality and policies. Notably, he does so through a strategic marriage to the daughter of a key ally, the Rajput king of Amer, and through his decision, roughly a year later, to abolish the pilgrimage tax on non-Muslims, a signal of his growing tolerance for the religion of the majority of his subjects and of his willingness to defy more orthodox Islamic elements within his court.

This much is a matter of historical record, though the emperor’s motives have predictably been subject to varying interpretations (whereas early Congress leaders tended to project him as a broadminded symbol of an enlightened “secularism,” latter-day Hindu nationalists often portray him as a wolf in sheep’s clothing, co-opting guileless Hindus with an only superficially kinder, gentler Islam). But the film’s central storyline is, in the grand tradition of “historical” films, decidedly off-the-record: it focuses on the budding love between Akbar and his first Rajput bride (called, per popular legend, Jodhaa, though her actual name is debated by historians), and alleging that it was her proud and stubborn allegiance to Hindu lifeways that was instrumental in shaping the emperor’s adult personality and policies. Jodhaa herself is thus central to the film, and the director’s choice of placing her name before Akbar’s in the title clearly suggests other culturally-charged pairings, such as (for Hindus) Sita-Rama and Radha-Krishna, and (in the Sufi allegorical world) Shirin-Farhad and Laila-Majnun.

Indeed, that this is a match made in heaven will be one of the implicit arguments of the film. Gratifyingly, Aishwarya Rai Bachchan proves equal to the assignment; she has become, with time, more than a pretty face, and in her poise and dignity she seems perfectly paired with her leading man. Like him, she gives a multifaceted performance: at times proud and sure of herself, at others vulnerable or simply confused in the strange new world of the imperial harem. Slowly she moulds herself into an unmistakable empress.

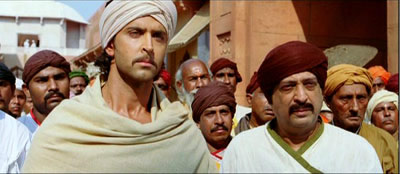

For his part, Hrithik Roshan delivers a performance of great conviction and considerable seduction, giving us a young Akbar who combines sensitivity with abs of steel. His muscles are on display during an elephant-taming sequence early in the film, when he impresses his future father-in-law, and even more so during a later scene in which Jodhaa surreptitiously watches him working out with a sword, shirtless, on a terrace; the camera, mimicking her gaze (and thus giving license to viewers of either gender to follow it) pans slowly over his gleaming arms and torso, “noticing” each detail of what is, indeed, an almost preternaturally magnificent physique.

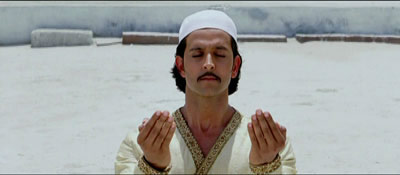

Yet this hunk displays a vulnerability and gentility, coupled with a devotion to ethical principles—as when he assures Jodhaa, on their nuptial night, that he will not impose himself on her against her will—that is consistently disarming, credible, and affecting. His Islamicate body language—as when he prays at the Chishti shrine of Moinuddin of Ajmer prior to his marriage, or abandons himself to a trancelike Sufi dance during the ceremony—actually seems to lighten the density of the actor’s build to effectively evoke the mystical dimension of Akbar’s personality, as recorded by his devoted court chronicler and friend Abu’l Fazl.

Despite his occasional rages—as in his peremptory execution of the traitor Aadham Khan by having him hurled head-first from the parapet of Agra Fort (an event that occurred in May, 1562)—and the camera’s ongoing fascination with absolutism-as-spectacle (as in the massive court scenes), this is a monarch who, in the film’s unhurried unfolding, we get to know well and find it hard not to like—which may explain why some on the Hindu Right thought the film so distasteful.

There are plenty of strong supporting performances as well. Of special note is Ila Arun’s portrayal of the steely Maham Anga, once Akbar’s wet-nurse and later a trusted mentor, but, here, Jodhaa’s nemesis at court, in part because of her opposition to the new queen’s unconcealed Hindu identity. It would have been easy to merely villainize her, but Arun gives her enough depth—as a palace woman who knows that her power depends on her access to the emperor, and who must stoically endure even the death of her own headstrong son at the latter’s command—that when her fall eventually comes, Akbar’s verdict that he will never look at her face again falls like a terrible blow; her expression of utter devastation can only arouse pity. And as a glowering but benevolent courtier named Chugtai Khan, Rajesh Vivek continues his unbroken track record of playing an appealing Hanuman-like sidekick to the heroes of Gowariker films.

In crafting what is (among other things) a prequel to the most famous prior “historical” film of Bombay cinema—K. Asif’s monumental MUGHAL-E-AZAM (1961), which centers on the aging Akbar and Jodhaa’s fictional struggle, ca. 1600, with their wayward son Salim, who has given his heart to a lowborn court dancer—Gowariker nods to his famous predecessor with an opening relief-map of India accompanied by a God-like voiceover (supplied by Amitabh Bachchan, of course) that positions the Mughals, as did Asif’s talking “Hindustan,” as the end and exception to a series of rapacious Central Asian invaders: as conquerors who loved India and settled down to finally make it their home (ignoring, of course, more than three hundred years of well-settled Delhi sultans, and Muslim kings in Jaunpur, Bengal, etc.). This leads into a restaging of the Second Battle of Panipat (1556), in which the army of the fourteen-year-old Akbar, under the leadership of his regent Bairam Khan (Yuri), defeats the Hindu king Hemu who has usurped the throne of Delhi. Though MUGHAL-E-AZAM was known for its colossal battle scenes, chockablock with elephants and recreations of early cannon, cinematography and special effects technology have come a long way since 1960, and the camerawork here (and in a single later battle sequence) positions us in the gory center of combat, as two huge armies clash on a dusty plain. The scene is brief, however, and ends with Akbar’s refusal, following the claim of some historians, to behead the wounded and humiliated Hemu in order to assume the title of ghazi or “warrior of the faith.” The irritated Bairam Khan then does so in his name, which becomes a prelude to the emperor’s decision, following a similar victory six years later, to relieve the Regent of his power and send him on a holy trek to Mecca—the ironic fate of several overzealous Muslims in the film. This is soon followed by the emperor’s decision to accept the Amer ruler’s offer of his daughter’s hand, with which the main storyline begins in earnest: the exploration—briefly interrupted by intrigues, an assassination attempt, and rebellions by brothers-in-law—of the question: “will she eventually give her heart (and body) to him?” Take a wild guess....

Like the film itself, the musical score, although not one of A. R. Rahman’s catchiest, has a dignity and charm that slowly grows on one. It also has a measured symmetry, with four principal songs apportioned evenly between the two halves of the film (a fifth, the non-diegetic Jashn-e-Bahara or “joys of spring,” mainly serves as a prelude and bridge to the final romantic ballad). Each has a distinct melody and mood, and is used as background music through a number of scenes other than the one in which it occurs as a lyric, giving the whole structure almost the feel of a symphony in the traditional four movements. The first half of the film, centered on the inter-religious marriage of the principals, is structured around the graceful qawwali Khwaja mere Khwaja (“Oh my Master,” a paean to Moinuddin of Ajmer, the founder of the Chisthi order of Sufis, to whom Akbar and other Indo-Islamic kings displayed great devotion), and Mana mohana (“Enchanter of the heart”), a bhajan to Krishna that evokes the lyrics in the Braj Bhasha dialect of Hindi composed by such Mughal-period poet saints as Surdas and Mirabai.

The former is performed during the royal wedding by a group of dervishes costumed and choreographed to evoke the famous “whirling” Mevleviye of Konya, followers of Rumi; though this sounds hokey, the sequence—with its nighttime royal camp setting, smoking torches, and slowly-building mystical mood—is strangely effective, plausibly leading to one of Akbar’s (attested) experiences of being bathed in divine effulgence.

The insertion of the bhajan underscores the Mira-like subtext of Jodhaa’s filmic biography: married against her will to a man not initially of her liking, she carries a cherished image of Krishna with her and installs it in the palace, singing to Him in her loneliness (visitors to Fatehpur Sikhri are routinely shown the niche in which, according to local guides, Jodhaa’s chosen deity was placed). When her voice (improbably) carries into the public audience hall, it further irritates the maulvis who have been complaining about the introduction of “idolatry” into the Fort, but its effect on Akbar—at once (like much bhakti verse) devotional and seductive—signals the beginning of a thaw in the newlyweds’ icy formality.

The second half of the film focuses on Akbar’s triumph as a conciliatory ruler, who seeks to govern justly and compassionately; this is epitomized in Azeem-o-shaan Shahenshah (“O great and glorious Emperor!”), a rousing anthem performed during a public celebration of Akbar’s birthday (when he would be ceremonially “weighed” in a balance with gold and jewels that were later distributed to the poor). Though the Mughals certainly knew how to deploy spectacle to strategic effect, especially through elephant processions and elaborately-staged darbars that were later imitated by the Brits (Akbar’s Speer and Riefenstahl were the architects of Fatehpur Sikri and the atelier of court painters who created the Akbar-nama, celebrating his achievements in lapidary illuminations), the precision choreography of this impressively massive sequence seems more evocative of the national-triumphalist display of a modern Republic Day Parade or Asiad opening ceremony.

The ultimate consummation of Jodhaa and Akbar’s union—as close to a “climax” as the film provides—is handled with a discretion bordering on holy awe (Aishwarya-Jodhaa being, of course, already married into another Royal Family), and sealed, naturally, with a song rather than a kiss. After a mutual declaration of love for which Akbar (and Gowariker) carefully awaits the perfect moment, the royal union is tastefully choreographed to lovely and appropriately Sufi-esque lyrics by Javed Akhtar; the refrain of which declares (invoking the kalmaa or “profession of the faith,” the declaration that accompanies conversion to Islam):

In lamhon ke daaman men, paakeeza se rishte hain

Koi kalmaa mohobbat ka, dohraate farishte hainEnfolded in these moments are bonds so pure and holy,

Like the Profession of Love, ceaselessly chanted by angels

Big “historical” films are best understood (and not just in India) as ideologically imbued fantasies that use an imagined past to comment on the present. Set against the longue durée of South Asian narrative, Gowariker’s “historical”—the work of a youngish director known for his idealism—evokes several precursor traditions. One is the corpus of work in Sanskrit and regional languages that treat of the ideal Indian king: one who governs strategically, compassionately, and wisely, combining savvy real-politik with spiritual vision, or, put another way, the social functions of the kshatriya (warrior-aristocrat) and brahmana (priest-scholar) social orders—the South Asian equivalent of Plato’s philosopher-king. Another is the tradition of romance literature, also centered on kings but in less a didactic than an entertainment mode, that tests a young ruler through a series of trials, worldly and otherworldly, the successful completion of which enable him both to become a celebrated monarch and also to win a semi-divine (or divinely-beautiful) bride. The Sanskrit locus classicus for this may be the Shakuntala story as composed by Kalidasa, but a thousand years later the theme recurred repeatedly in a series of Hindi epic poems by Sufi authors, combining Persian romance motifs with others borrowed from Hindu mythology and folklore: the celebrated premakhans composed in the Jaunpur region of modern Uttar Pradesh, such as Malik Muhammad Jayasi’s Padmavat (ca. 1540), that is considered among the masterpieces of pre-modern Hindi literature. Kalidasa’s play probably reflects the imperial aspirations of the Guptas, and the Sufi epics may show the concern of Jaunpur patrons to assert their cultural independence from the Sultans of Delhi. Merging these two thematic currents in Jodhaa Akbar, Gowariker takes his ideological stand in a line of post-Independence filmmakers who have sought, maybe a bit too obviously at times, to heal the deep wounds inflicted by religious nationalism and its most fateful consequence—Partition, and the unending bloodletting that, through the manipulations of self-serving politicians and narrow religious ideologues, it has continued to spawn. This is an effort, and a film, of real nobility.

An insightful essay on Jodhaa Akbar appears in the lavishly-illustrated volume Islamicate Cultures of Bombay Cinema by Ira Bhaskar and Richard Allen, published by Tulika Books (New Delhi: 2009), pp. 153-68.

[As noted above, the UTV DVD of JODHAA AKBAR presents the film on two disks, with a third “special features” one included as well. Image and sound quality are fine, but what is most remarkable are the optional English subtitles by Nasreen Munni Kabir, noted documentary filmmaker, Hindi film scholar, and author of a multilingual and multi-script rendering of The Immortal Dialogue of K. Asif’s Mughal-E-Azam (Oxford University Press, India: 2006). Kabir has done superior subtitling of Hindi films before—for the BBC-4 film series and for another broadcast by Turner Classic Films in the USA, and she was an ideal choice for this project. That she is credited for it onscreen (a first, to my knowledge) is also a hopeful sign that one Bombay director, at least, realizes the difference that good subtitles can make to a film’s reception. (Given the occasional difficulties of some of Akbar’s Persianized khaalis Urdu, some present-day Hindi-speaking viewers may benefit from these as well.) Turbans off, again, to Gowariker and his production team.]