KARZ

(“The Debt,” Hindi, 1980, approx. 193 minutes)

Directed by Subhash Ghai

Screenplay: Sachin Bhowmic; Dialogue: Dr. Rahi Masoom Reza; Lyrics: Anand Bakshi; Music: Laxmikant, Pyarelal; Cinematography: Kamalakar Rao

The highly successful masala films of Subhash Ghai may best be situated in the artistic lineage of Manmohan Desai, though they are often more incoherent and derivative, and politically more conservative and even jingoistic than those of the madcap auteur of the previous decade. One of Ghai’s first big hits, KARZ remains something of a standout in his oeuvre because of its greater narrative cohesion and appealing reincarnation-based plot (which shows the influence of Bimal Roy’s celebrated 1958 film MADHUMATI), the enduring popularity of several of its songs and their picturizations, and its giddy and hyperbolic camerawork — all characteristics of the successful masalaopus of its era. If Ghai seldom appears to be an innovator in popular Hindi cinema, KARZ nevertheless displays him at his best: as an agreeably beguiling hack. The impact that this hit film, which is as much music-driven as plot-driven, had on a generation of young viewers (and future actors and filmmakers) has been wittily celebrated in Farah Khan’s extraordinarily entertaining OM SHANTI OM (2007), a film that induced me (and, doubtless, others) to go back and revisit KARZ. Viewed through the lens of Khan’s tour-de-forcehomage, KARZ acquires greater interest for those who didn’t actually grow up with it.

|

As the film opens, a young man named Ravi Verma (Raj Kiran) wins a legal battle to recover his family’s tea estate near Ooty (the nickname of Udagamandalam/Ootacamund, a hill station in Tamil Nadu) that had been seized by the (Anglo-Indian?) former partner of his father, one Sir Juda (the Shemaroo DVD’s rather dodgy subtitles first curiously Hindi-ize this as “Surjuda,” and later Anglicize it in spades as “Sir Tudor”!). Played by the aging and now paunchy Premnath, he is a typical specimen of the Ghai villain: vaguely “Western”/foreign, monstrous (unable to speak, he communicates with his henchmen through a sort of Morse code conveyed by tapping on whiskey glasses), and utterly ruthless.

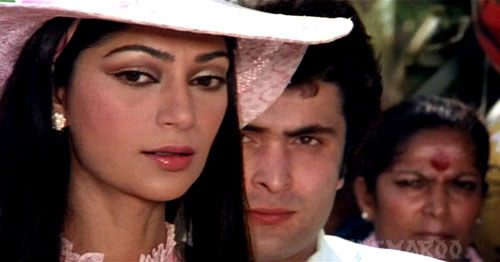

Sir Juda soon conceives a plan to regain the estate by contracting with Kamini (Simi Garewal), a wayward damsel (our first glimpse shows her lighting a cigarette—always a bad sign in women) with whom young Ravi is unwisely infatuated. By agreeing to marry Ravi and then dispose of him within several days, the widowed Kamini will, through a legal loophole, win back the property for Sir Juda and secure for herself the status of “queen” of its palatial home, along with a queenly income of Rs. 25,000 per month.

As the newlyweds drive through the estate and listen to Ravi’s favorite rock tune on the jeep radio (with a guitar riff that will serve as a leitmotif throughout the film and the melody of its most celebrated song, Ek hasina thi), Kamini contrives a car “breakdown” near an isolated shrine to goddess Kali and then drives over her unfortunate spouse while he is lecturing her about his mother’s love—a murder artfully (and lengthily) staged to highlight Kamini’s sadistic depravity and to make Ravi a blood sacrifice to the ambivalent cosmic Black Mother who is sole witness to his death.

We never learn how this “accident” is explained to Ravi’s adoring mother (played by the great Durga Khote) and sister Jyoti/a.k.a. “Pinky” (Abha Dhulia), but the former is evidently a Kali devotee, and she harangues the goddess (in the form of a bazaar poster) over her son’s untimely death, an injustice done by one Mom to another. Her insistence that Kali will have to give back her son in order for him to pay the “debt for milk” (dudh ka karz) that he owes her leads into the film’s title sequence, which is superimposed over the first musical number featuring Ravi Verma’s reincarnation, roughly twenty years later, as a pop idol named Monty (Rishi Kapoor). |

|

|

|

Yeh paisa (“this cash”) is visually a riotous mélange of flashing disco lights, revolving stages, chorus lines, and costumes vaguely suggestive of a postmodern Cossacks-meet-Gauchos sock hop—the imaginary world of middle class youth culture and “pop music” (which virtually did not exist outside of the cinema in 1980’s India) inspires a desisendup of a downmarket Las Vegas revue. In what would become another Ghai trademark, the director makes a cameo appearance in the sequence—though this is not this “murder mystery” film’s sole debt to Hitchcock. The flashy “money” motif of the song (a huge rupee coin dominates the stage and much of the lyrics consist of counting from one to ten) introduces the orphan Monty’s loveless relationship with his greedy adoptive “father” and manager, Mr. G. G. Oberoi (Pinchoo Kapoor), who manipulates Monty’s career to his own advantage. When Monty’s boyhood friend Dayal comes to visit, the woebegone star gets teary over his lack of a mother’s love. Dayal’s invitation to a party at his boss’s home leads to Monty’s first meeting with Tina (Tina Munim), a visiting schoolgirl with whom Monty promptly falls in love, expressed through the song Dard-e-dil (“You’ve aroused pain in my heart”). His third song follows soon after (a mere thirty-seven minutes into the film): “Mere umar ke” (“O young men like me [don’t fall madly in love]”) is another disco tour-de-force, in which Monty cavorts in a silver lamé outfit on a giant LP turntable commemorating the 50th anniversary of the HMV music label in India (“His Master’s Voice,” a colonial-era subsidiary of the multinational EMI). More lyrics about the pain of unrequited love lead, improbably, to a chorus refrain of the Vedic mantra “Om shanti om” (in another postmod turn, the subtitles render the sacred syllable “ohm”)—presumably, a sort of prayer on behalf of the lovelorn, and the source, three decades later, of Farah Khan’s punning title for a film that opens with a reprise of this sequence. The song and refrain are wildly catchy, and its finale, when giant “oms” in Devanagari script descend from above amid soap bubbles and rainbows, is a cathartically bewildering bricolage. Asked for an encore, Monty begins playing the same guitar tune that Ravi Verma had enjoyed just before his death—leading to a series of flashbacks to the murder that cause Monty to faint on stage. This segues into a hospital sequence in which Monty’s head is checked and white-coated doctors speculate on whether his hallucination might be from a previous birth—but conclude (being modern rationalists) that it is merely “psychosis” (!) and prescribe a month’s rest-cure in a hill station. As fate would have it, Monty packs off to Ooty. Since this resort town was the site of his murder as Ravi Verma and is also the location of Tina’s boarding school (the Verma Convent School, founded by Ravi’s dad), Monty is able, in time, both to investigate the fateful end of his previous life and to pursue his (romantic) end in the present one. |

|

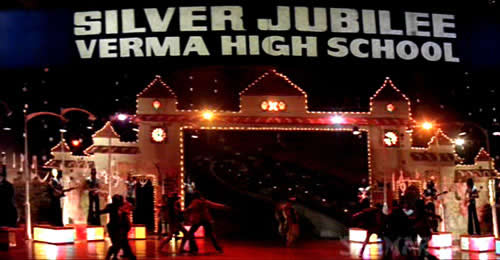

Naturally, both pursuits will require more songs: for Monty and Tina’s romance, a reprise of Dard-e-dil and then the coyly erotic duet Main solah baras ki (“I’m sixteen years old”), which showcases the attractions of Ooty and also provides Monty with his first glimpse of his former home, now the mansion of Queen Kamini—which occasions more flashbacks. They also require a subplot providing comic interest via Tina’s “uncle” Kabir/Kabira (Pran), a lovable thug who has worked for and also been double-crossed by the Queen. He introduces himself as an orphan raised by a kindly Muslim who gave him the Arabic name (“the great one,” an epithet of Allah) of the eclectic 15th century North Indian poet-saint, and he sprinkles his speech with doha couplets that parody those of his namesake. After briefly testing Monty, Kabir gives his blessing to his desired union with Tina, and then assists him in unraveling the mystery of Ravi Verma’s death. Kabir knows only that a former servant on the estate (who was, incidentally, Tina’s drunkard father) was murdered ten years earlier for having overheard a conversation between Kamini, her brother, and Sir Juda’s gang concerning the Kali temple and Ravi Verma; Kabir himself was framed for this murder and spent a decade in prison, having blackmailed the Queen into raising Tina royally (hence the high class boarding school) by implying that he knew all that the servant had heard. Monty is now able to provide the missing links (i.e., what happened at the Kali shrine), and Kabir and he begin plotting revenge on the Queen. Along the way, they find (thanks to Kabir’s prayers to Parvardigar, an Islamic name for “God the sustainer”) Ravi’s sister, now reduced to poverty and servitude after being expelled from the estate by Kamini. This discovery lifts Monty from a downward spiral of alcoholism and near-madness, and he is soon reunited with his mother too, who regains the power of speech and hearing (lost in her grief over Ravi) on seeing Monty, whom she immediately recognizes—Kali be praised!—as her returned son. To elicit a confession from Kamini, Monty pretends to woo her, an overture to which she gradually responds, especially when he escorts her to the bizarre feast day of a local Sufi-cum-tribal holy man/deity, Gubare Wale Baba (“balloon-guy saint”—a yogic figure with the head of a donkey!), occasioning the particularly excessive item number Kamal hai(“It’s amazing!”) performed by Kabir and his cronies and featuring a cameo dance performance by the Helen-like Aruna Irani. From here on, Ghai piles on his characteristic overload of complications, permutations, and near-misses for all concerned, deferring the inevitable denouement of Kamini’s confession and comeuppance and Monty/Ravi’s marriage to Tina as the scion of the restored Verma clan. It all comes to an emotional climax during and immediately after Monty’s performance at a charity show celebrating the silver jubilee of the Verma School and inaugurating its new theatre, Ravi Varma Memorial Hall, with Queen Kamini as chief guest. On this occasion Monty sings the film’s best-known hit, Ek hasina thi (“There was a young beauty”) in which he gradually reveals and restages each detail of Ravi’s betrayal and murder — a song that provided melodic, lyrical, and visual inspiration for Om Shanti Om’s similarly climactic title number. The denouement that follows displays a striking disregard for visual continuity (a car chase instantly switches from night to day), but manages, amidst near bedlam, to tie up most of the loose ends in the ample plot. But if the conclusion doesn’t make you dizzy, the camerawork certainly will; Ghai’s cinematographer, Kamalakar Rao, misses no opportunity to deliriously spin the camera, though he varies this occasionally with split screens, double exposures, and upside-down images: all suggestive, in 1980 Bombay, of an ultra-hip mod-disco sensibility exemplified by the popularity in India of musical groups like Abba, and in perfect synch with Monty’s ever-changing wardrobe. |

|

[The Shemaroo DVD of KARZ has tolerable image quality (though the company’s logo regrettably remains visible throughout) but offers poor and sometimes misleading English subtitles. Song lyrics are, however, subtitled.]