OMKARA

(Hindi, 2006, approx. 155 minutes)

Directed by Vishal Bhardwaj

Producer: Kumar Mangat; Screenplay: Vishal Bhardwaj, Robin Bhatt, Abhishek Chaubey; Dialogues: Vishal Bhardwaj; Music: Vishal Bhardwaj; Lyrics: Gulzar; Cinematography: Tassaduq Hussain

Composer/director Vishal Bhardwaj’s transposition of the story of “Othello” to the landscape and culture of contemporary eastern Uttar Pradesh (UP) is a triumph of conception, cinematography, and acting. Though it enjoyed only modest success in its initial release, it was critically acclaimed (nominated for eighteen Filmfare awards, it ultimately garnered half that number, as well as many other prizes) and stands as a worthy successor to such renowned cinematic Shakespeare adaptations as Akira Kurosawa’s THRONE OF BLOOD (1957) and Bhardwaj’s own MAQBOOL (2003). Exemplifying the ability of the occasional big-budget Bombay production to venture into unconventional terrain, it casts major stars in challenging and atypical roles, resulting in uniformly strong performances (and one extraordinary one, by Saif Ali Khan, as the story’s convoluted villain). As in MAQBOOL, the director assigns his characters locally suitable names that aurally suggest their Shakespearean archetypes.

| Character: | Actor: | |

|---|---|---|

| Omkara Shukla/ “Omi” | [Othello] | Ajay Devgan |

| Ishwar Tyagi/ “Langda” | [Iago] | Saif Ali Khan |

| Dolly Mishra | [Desdemona] | Kareena Kapoor |

| Keshav/ “Kesu Firangi” | [Cassio] | Vivek Oberoi |

| Billo Chamanbahar | [Bianca] | Bipasha Basu |

| Indu | [Emilia] | Konkona Sen Sharma |

| Rajan Tiwari/ “Rajju” | [Roderigo] | Deepak Dobrial |

| Bhaisahab | [Duke of Venice] | Naseeruddin Shah |

Although the film dispenses with the trope of “race” that is generally highlighted in stage productions of “Othello” (despite a lingering controversy over the actual “blackness” of Moors—a term somewhat carelessly applied, in Elizabethan times, to people of varied permutations of North African, Arab, and Spanish descent), it substitutes other markers of difference that strongly resonate in everyday life in north India, and are capable of eliciting the powerful sense of alterity that the tale requires.

Most of the main characters’ surnames (Mishra, Shukla, Tiwari, Tyagi) identify them as Brahmans, as does the appearance and deportment of the politician Bhaisahab (“elder brother”). “Brahmans” make up a relatively high percentage of the population of UP (they accounted for 12% of the population in the 1931 census, the last to designate such distinctions), but the conventional understanding of the “caste system”—by which traditional priest-scholars are routinely labeled as the “highest” social group—does not account for the vast range of occupations and socioeconomic levels of people who claim this designation, nor for their internecine and often impassioned negotiation of relative status based on alleged purity of bloodlines. In Bhardwaj’s film, it is revealed early on that Omkara’s Brahman father sired him on a lower-caste woman—a blemish on the son’s character that his enemies regularly invoke, calling him a “half-Brahman” (adha-Baaman) and, literally, “half-breed” (adha-jaat). Actor Devgan’s swarthy complexion and “unrefined” features contrast starkly with Kareena Kapoor’s ethereal looks and European-like fairness—the latter the single most important marker of good breeding and (especially feminine) “beauty” in the north Indian context (cf. the flourishing cosmetic trade in “skin lighteners” such as “Fair & Lovely”). There is a social difference as well; Omkara is a lumpen hero who resides in a rural extended family and has acquired power through his strength, panache, and loyal service to Bhaisahib. Dolly is the daughter of a prosperous urban lawyer and is college-educated; indeed, the fact that she attended the same college as the student leader Kesu (whom Omkara’s gang members dub “Firangi” or “outsider/foreigner” because of his urban background) will eventually be used by Langda/Iago to nurture Omkara’s suspicion that she secretly loves Kesu, who is more her equal in education and social position.

The storyline follows the plot of “Othello” fairly closely. As the film opens, Langda warns Rajju that his intended bride, Dolly, is being abducted by the powerful but socially-tainted Omkara, and incites him to complain to Dolly’s father. A violent confrontation between the enraged lawyer and the abductor is averted, through Bhaisahab’s intervention, by Dolly’s confession of her love for Omkara and her willing collusion in the overturning of her father’s arranged-marriage plans for her. Although the lawyer bitterly renounces his claim over Dolly, he warns Omkara that “A girl who can deceive her own father can never be possessed by anyone else”—planting the seed of suspicion that Langda will soon begin watering. The harm wrought by patriarchal ideology that obsessively posits the need for male authorities to “control” female sexuality—a theme implicit in “Othello”—becomes more explicitly highlighted here, and is developed through the later interactions of Dolly, her confidante Indu, and Omkara.

Shakespeare’s villainous Iago has often been considered the most complex and interesting character in “Othello”; in contrast, its eponymous hero is portrayed as both less verbose and more simple and instinctual in his responses, which facilitates his manipulation by Iago. In Saif Ali Khan’s Ishwar/“Langda,” Bhardwaj gives us a truly worthy Iago: an ambitious man marred by a physical disability (langda means “lame, crippled,” and he walks with a pronounced limp), he is married to Omkara’s younger sister, Indu, and is plotting his own ascent to the position of mahabali (“general”), the second-in-command of Bhaisahab’s considerable forces.

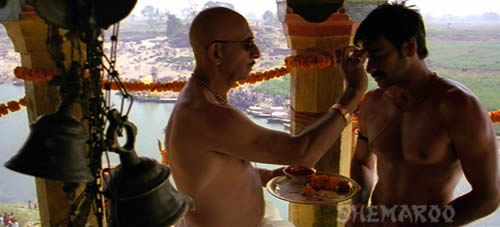

That he resents his superior is clear from his opening speech to Rajju, in which he bitterly alludes to Omkara’s mixed birth, but his malice grows after Omkara, in a surprise move (and in a spectacular scene staged in a temple on a bluff overlooking the Ganga) passes over him to promote Kesu to themahabali post, due to the latter’s influence among student cadres in Bhaisahab’s political empire. From this point on, Langda systematically manipulates Rajju, Kesu, and Omkara to bring about the destruction of the latter two. He is helped by his wife’s innocent “borrowing” of a valuable jeweled waist-chain—an auspicious and erogenous family heirloom that Omkara had presented to Dolly in preparation for their formal wedding ceremony (which has been deferred to an astrologically favorable date). Langda in turn steals it from his wife and gives it to Kesu, ostensibly to help the latter in his on-again, off-again relationship with the voluptuous showgirl Billo, but of course with the secret agenda of convincing Omkara that Dolly has lavished this gift on her supposed paramour.

This complex transfer of the equivalent of Shakespeare’s embroidered handkerchief does its intended job, helped along (in a suitably updated move) by a misleading mobile phone conversation between Kesu and Langda that Omkara is made to overhear. The rest is, more or less, theatrical history, though the manner in which Othello’s awful destiny plays out—on his and Dolly’s wedding night, and with a surprise twist in the fate of secondary characters that further compounds the carnage—achieves remarkable tragic and cinematic power.

As was the case in the director’s earlier Maqbool, the film’s concessions to commercial cinema conventions are evident but muted; although there are six engaging songs, only two are diegetic (Beedi and Namak; these are “picturised” by Billo/Bipasha Basu, whose ravishing beauty itself seems rather too good for the tawdry milieu of provincial stag parties in which she gyrates); the others are on the soundtrack only, as is standard in Hollywood films. They thus poetically but coolly suggest the emotions of characters without requiring that these be voiced on-camera, even as they serve, in conventional Bombay cinematic fashion, to advance the storyline and enhance its emotional texture (thus, e.g., the first song, Naina thag lenge, “Your eyes will betray you,” is a flashback that reveals the process by which Dolly fell in love with Omkara). In addition to Saif Ali Khan’s remarkable portrayal (deservedly rewarded with the Filmfare trophy for “best villain”), all the A-list stars offer solid and convincing performances, with Kareena Kapoor’s endearing Dolly and Vivek Oberoi’s guileless Kesu deserving of special mention. Even Ajay Devgan’s sullen scowl and somewhat monochromatic “cool,” too-familiar from other films, seems particularly effective here in evoking Shakespeare’s grim Moor. The other principals—Dobrial, Shah, and Sharma—all shine as well. The cinematography and mise-en-scene deserve special mention: although a good part of the location work was actually done in Maharashtra, the evocation of eastern UP is splendid and convincing, evoking its juxtapositions of human squalor and degradation with eruptions of hieratic spectacle and architectural and scenic beauty.

Bhardwaj’s choice of social milieu for his meditations on Shakespeare’s tragic tales of kings and generals continues to be interesting. In setting both MAQBOOL and OMKARA among criminals (albeit in each case these local “big men” are closely tied to ruling elites), he simultaneously draws on the legacy of the gangster film as a vehicle of high drama and intense emotion, and pointedly highlights a reality in today’s India: the volatile intersection of the economic and social aspirations of a vast and restless underclass with a democratic system dominated by corrupt and often criminalized politicians. Although there is some attempt (through dialog, camerawork, and the title song “Omkara,” which occurs early in the film) to cast the protagonist as a sympathetic proletarian champion, most of the action does little to refute Dolly’s father’s assessment of him as a goonda (“hoodlum”)—a thug recruited as an enforcer by a local demagogue. The routine involvement of Omkara, like the earlier Maqbool, in gory violence—here, the bullying and even assassination of Bhaisahab’s political opponents—is treated casually and seems almost incidental to each story. Certainly, it is not meant to detract from our identification with these tragic heroes, although it also seems to invite a certain disquiet at its stark portrait of contemporary Indian society, or perhaps of human society in general, as a predatory realm in which only the ruthless survive—and they, too, not for long.

[The Shemaroo/Eros DVD of OMKARA offers good image quality, though unfortunately the viewing experience is marred by a large company logo (visible in the shots displayed above) that continually hovers in the lower right of the screen. Subtitles accompany both dialog and song, and make a brave (and generally effective stab (albeit chutiya—literally, “little cunt”—becomes mere “idiot”) at rendering the rustic eastern Hindi dialog and slang used by most of the characters.]