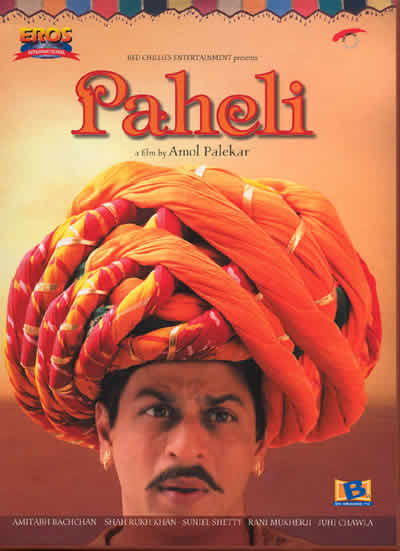

PAHELI

(“the riddle”) Hindi, 2005, approx. 150 minutes

Directed by Amol Palekar

Produced by Gauri Khan and Red Chillies Entertainment

Based on the story “Duvidha” by Vijaydan Detha; Screenplay and Dialog: Sandhya Gokhale; Costumes: Shalini Sarma; Art direction: Muneesh Sappel; Background score: Aadesh Shrivastava; Choreography: Farah Khan; Lyrics: Gulzar; Music: M. M. Kreem; Cinematography: Ravi K. Chandran

This richly entertaining film gives a refreshing new twist to two hardy perennials of Indian storytelling: the tale of the seduction of a married woman by a phantom or demi-divine lover who assumes the guise of her husband; and the cinematic trick-motif of the double, which affords not only the thrill of seeing a popular actor in two different roles, but also a culturally-favored dramatic externalization of psychological complexity and conflict: a “divided self” appearing in multiple bodies. Skillfully building on several bases—a traditional folktale with ancient roots, reworked as a modern short story (by famed Rajasthani writer Vijaydan Detha) and then an art film entitledDuvidha (“the dilemma”)—director Palekar (backed by Red Chillies, a production company started by Shah Rukh Khan and his wife Gauri) achieves something remarkable: a mainstream, big-budget film that is also witty, visually seductive, and (in the last analysis) tantalizingly ambiguous in message—a “riddle” that viewers may ponder and savor.

The locus classicus of the story may lie in the (ca. 5th century BC?) Ramayana tale of Ahalya, the most beautiful woman on earth, who is married to the dour sage Gautama but coveted by the lustful king of the celestials, Indra, who wants to bed her both for his own pleasure and in order to curb her husband’s spiritual power (which, in patriarchal ideology, depends in part on the chastity of a wife). One day when Gautama goes off to take a bath, Indra assumes his form and enters the couple’s hut. He and Ahalya get right to business, but Gautama returns unexpectedly (forgot his towel?) and discovers them in flagrante delicti. The enraged husband pronounces nasty curses on both of them: in different versions, Indra is castrated and/or marked with vulvas all over his body (giving rise, some say, to his epithet of being “thousand-eyed”) and Ahalya is condemned to eons of invisible, insentient existence — often understood as being transformed into a boulder — until she will eventually be touched and purified by the feet of the young Rama. But besides being beautiful, Ahalya was also smart, and a special fascination of storytellers has always been with the pregnant question: Did she know what she was doing? One finds both possible answers in classical texts: that she was truly fooled by Indra and hence “innocent,” though punished nevertheless; or that she recognized the god in his disguise, but was flattered…. or curious…or sexually frustrated, and went ahead anyway.

The Ahalya story gets radically turned around in some regional folktales—evidencing feminine input, or the worldview of lower class communities in which women had more power—such as the Kannada story of “the serpent lover” translated by A. K. Ramanujan. Here a cobra-deity, helped by a magic potion, falls in love with a young wife who has been abandoned by her reprobate husband and begins visiting her by night in his form. When the wife becomes pregnant, her real husband denounces her, but her snake lover cleverly instructs her on how to pass a truth-test before the king, as a result of which she is praised by everyone as a chaste wife. Eventually she gives birth to a handsome son and wins her husband back—though her serpent paramour, tortured by separation, finally commits suicide by hanging himself in her tresses. The story throughout invites sympathy for the frustrated, neglected wife, and invites listeners to delight in how she (with snaky prompting) hoodwinks all the arbiters of social morality. Far from being punished for her extra-marital affair, she ends up with a loving husband, a beautiful child, and a stainless reputation—not to mention (enroute to this summum bonum) great sex every night.

Palekar’s cinematic legend is closer in narrative and spirit to the folktale than to the classical one, but it takes an unusually compassionate and probing interest in both husband and wife—indeed, its delightful but puzzling ending permits it to be read as (among other things) a dual coming-of-age tale. As the film opens, Lachchi (Rani Mukherji) is being prepared for marriage to Kishenlal (Shah Rukh Khan), the son of a fabulously wealthy merchant of Navalgarh, and her girlfriends tease her (via the song Aaadhi raat jab, “At midnight, when…,” which accompanies the credits) of the sleepless wedding night to come, and recommend coquettishly “resisting” her husband’s advances.

These chidings prove ironic and unnecessary, however, for the shy, simple-minded Kishenlal is a workaholic drudge, forever doing sums in order to earn the approval of his gold-hungry father Bhanwarlal (Anupam Kher, in a brilliantly satiric portrayal of the business ethos stereotypically associated with the Marwari trading community). On the couple’s first night together, Kishenlal looks up from his books only long enough to announce that he must, by paternal decree, leave first thing in the morning for a five-year posting in a distant trading town. Declaring, “What is the point of igniting the spark of passion for just one night?” he leaves his beautiful bride alone in bed to cry herself to sleep. Fortunately for Lachchi, someone else loves her: a shape-shifting bhut who became infatuated with her when the wedding party, enroute home, stopped to rest at a haunted caravanserai and step-well (baoli).

The Sanskrit word bhuta (pronounced bhoot in Hindi) is a past participle of the verb “to be,” so literally a “has been”; though usually translated (as in the subtitles here) “ghost/spirit.” Sometimes portrayed in narrative as a nasty sort of revenant who can possess and torment living humans, in the fluid supernatural ecosystem of Indic folklore the term can also connote (as in this story) a demi-divine being with extraordinary powers. Lachchi’s bhut (who first appears as a crow, then as several other animals, a bluebird, and a peasant, before finally assuming the form of Kishenlal/Shah Rukh) is a tricksterish immortal who refers to himself as a mayavi (a sorcerer or “illusionist”), but apart from his digitally-enhanced shape-shifting skills, he obviously possesses a good measure of wisdom and (most important for the story) a lot of heart. Unlike Indra in the Ahalya tale, but like the cobra in the south Indian one, he isn’t just looking for a one-night stand. Though his body is an illusion, his love is real, and so true that, having learned the terms of Kishenlal’s five-year absence and assumed his form, and having successfully re-entered the family mansion through a ruse, he cannot bear to deceive the one he loves. Hence he frankly confesses to Lachchi, in their first intimate moment, just who he is (and isn’t). What happens then — and for the rest of the movie — is interesting enough that I don’t want to reveal it here. It is also significant, I think, in light of the history of popular cinema’s representation of female agency — or lack thereof.

The film’s multi-course feast of delights include a strong score of six songs that are sensitively integrated into the storyline, gorgeous Rajasthani locations, sets, and costumes (the film offers a veritable “palace on reels” mini-tour, evoking an eternal, pre-modern Rajasthan), a script cast in a saucy Rajasthani-ized Hindi that is still readily comprehensible by speakers of the (standard) Khari Boli dialect (this distinction will of course be lost on foreign viewers, but fortunately the English subtitles are decent), and a pair of wisecracking kath-putli marionettes (digitally doctored and wonderfully voiced by Naseeruddin Shah and Ratna Pathak Shah) who provide a running commentary on the tale. Excellent supporting performances (including that of Juhi Chawla as Lachchi’s long-suffering sister-in-law, who has also been abandoned by her husband, and Dilip Prabhawalkar as Kishen's stoned-out uncle) culminate in a juicy cameo by Amitabh Bachchan as a blustery sheepherder (is there anything the Man can’t do?) whose ultimate (apparent?) solution to the film’s climactic “riddle” is like a tasty paan to round out the cinematic meal. And then there is the pleasant lingering aftertaste as one digests its happy but multiply-interpretable conclusion.

PAHELI’s ambiguity stems in no small measure from Shah Rukh’s fine execution of his dual role — both as the immature (but patently desirous and slowly-awakening) husband, and as his self-confident yet vulnerably-tender supernatural double. Their inevitable meeting is not just a chance for the film editor to show off the latest in “doubling” technology, but (in my own fanciful reading…with which my wife, who also liked the film, strongly disagrees) a real emotional conundrum that raises some delicious interpretive possibilities—e.g., of love as kind of permanent “possession,” and of maturity as the incorporation of a heretofore alienated shadow persona.

Reference:

"The Serpent Lover." In A. K. Ramanujan, A Flowering Tree and Other Oral Tales from India (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), pp. 155-158.

[The Eros International DVD of PAHELI has a good quality digitalization of the film, plus an interesting "making of" feature that includes some of the cast's interpretations of its themes. Subtitles are adequate and are provided for songs as well as dialog.]