PAKEEZAH

(“the pure one,” Kamal Amrohi, 1971)

Hindi, color, 175 minutes.

Screenplay and dialogue: Kamal Amrohi; Music: Ghulam Mohammed, Naushad; Lyrics: Kaif Bhopali, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Kaifi Azmi; Cinematography: Josef Wirsching

“I’ve seen your feet; they’re very lovely. Don’t set them down on the earth—they’ll get soiled.” This metaphorical warning-note, penned by a romantic stranger and left between the toes of a sleeping woman in a railway compartment, forms a much-underscored motif in this classic courtesan film—the final collaboration between the great actress and dancer Meena Kumari and her former husband, actor and director Kamal Amrohi. Like MOTHER INDIA, this film coexists with its own legend involving the offscreen lives of the director and star, who planned it together in the late 1950s but whose marriage broke up around the time that filming began in 1964. Kumari (who was also a talented Urdu poet under the pen name Naaz) then purportedly became an alcoholic, but eventually came back to complete the film shortly before her premature death in 1972; aficionados may try their luck at identifying—from Kumari’s pained and sometimes mask-like face—which scenes were shot when.

The central theme of the film is the struggle for respectability of a tawai’if, an Indo-Islamic courtesan trained in poetry, music, and dance—a glamorous “public woman” whose career was to be an elegant companion (and potential lover) to affluent men, but for whom a “respectable” marriage and home was out of the question. Her beautiful feet—apart from being an erotic fetish—represent her mastery of the art of North Indian classical dance or Kathak, which tawai’if’s preserved and nurtured for several centuries. The “earth” that such feet must perforce touch, however, is ruled by patriarchal society with its crippling double-standards, which decreed that respectable women (who lived in parda or seclusion) could seldom be interesting to men, and that interesting women were seldom respectable. All courtesan fiction struggles with this divide, which forms a principal theme of one of the earliest and most famous Urdu novels, Mirza Mohammed Hadi Ruswa’s UMRAO JAN ADA (1905; itself later filmed several times; see notes on UMRAO JAAN). PAKEEZAH offers another variation on the theme.

As the film opens, the beautiful tawai’if Nargis (Kumari) is “rescued” from her establishment in the notorious Chowk district in Lucknow by the nobleman Shahabuddin (Ashok Kumar), who has fallen in love with her and pledged to marry her. But when he brings her home bedecked in matrimonial red, his father denounces her as a “whore” who will ruin the family’s reputation; the horrified Nargis flees to a graveyard where, nine months later, she gives birth to a daughter and dies, leaving a note for her husband. The note, lost inside a book, finally reaches Shahabuddin nearly twenty years after Nargis's death, and the distraught father then sets out in search of his child. But Nargis’s courtesan sister Nawabjaan (Veena), who blames Shahabuddin for Nargis’s sad end, has taken the child to Lucknow, determined that she will never leave the Chowk “until she goes in a bride’s palanquin, blessed by her father.”

When Nawabjaan learns that Shahabuddin is looking for his daughter, now called Sahibjaan and already a famous dancer and singer (Kumari again, of course), she removes her again, this time to Delhi. Enroute, the midnight encounter with the stranger occurs, producing the romantic note which Sahibjaan treasures in an amulet case—a token of a man who might truly love her. After a dance performance in her new employer’s opulent “rose palace” establishment, Sahibjaan is packed off with a wealthy admirer for private service on a pleasure-barge, but before her “buyer” can enjoy his prize, the barge is wrecked by (yes!) a herd of wild elephants. Sahibjaan stumbles ashore to find the deserted tent of Salim (Raaj Kumar), a high-born forest officer, and as it turns out, the very man who once admired her feet in the train. Not only that, but he is also the nephew of (her lost father) Shahabuddin. Confirming his love for the possessor of the beautiful feet, Salim must now struggle to win his family’s acceptance of his intended marriage to Sahibjaan, and her own confidence that he can make this happen. In the process, those lovely feet will become (in the film’s most famous scene) not soiled, but bloody, willingly enduring the pain which is the signifier of true love.

The film's glorious, surreal sets form appropriate backdrops for its justly famous song and dance numbers, such as the cocquettishInhen logon ne ("These are the men [who have snatched away my modesty]") and the wistful Chalte chalte ("While going along [I met someone]"), both sung by Lata Mangeshkar.

On a straightforward narrative level, the film heavily endorses the ideology of bourgeois patriarchy, fixating on maintaining the physical virginity of Sahibjaan, which alone insures that she can become (as Salim renames her) “Pakeezah,” a “pure one,” worthy of marriage—which the film clearly regards as the summum bonum of a woman’s life. So un-subtle is this message that the name of the railway station at which Sahibjaan first reads Salim’s note is Suhag Pur—the town of suhaag, a culturally-loaded word connoting the auspicious state of a woman who enjoys the benefits of a living husband’s protection. In treating the tawai’if lifestyle as an unfortunate netherworld into which some good women inadvertently fall, the film elides the fact (so evident in the novel UMRAO JAN ADA) that many celebrated tawai’ifs were in effect highly educated career women, often accomplished poets and musicians, who valued their financial and personal independence from male authority. The much-repeated note, then, sounds a warning not to fall from the pure, marriageable state into the tawai’ifs’ debased realm. Yet paradoxically, its flowery Urdu prose is itself an evocation of that sensuous, refined, and altogether alluring world. And the flamboyant and color-saturatedmise en scene unashamedly celebrates the life of the Chowk and its denizens as a fairyland of gauzy veils, pirouetting figures, and playing fountains. The soundstage fantasy of these scenes contrasts sharply with the realistic footage of railroads (the film’s central vector of modernity), tumbled-town mosques, and seedy markets. This contrast evokes an inevitably bittersweet nostalgia for the vanished world of the tawai’if, which (in the film’s final shots) is enveloped in dust as Sahibjaan’s wedding palanquin sways out of sight. One wonders whether the domesticated wife she has now become will ever again have a chance to set down her lovely feet on a dance floor and stamp them imperiously to the beat of a tabla.

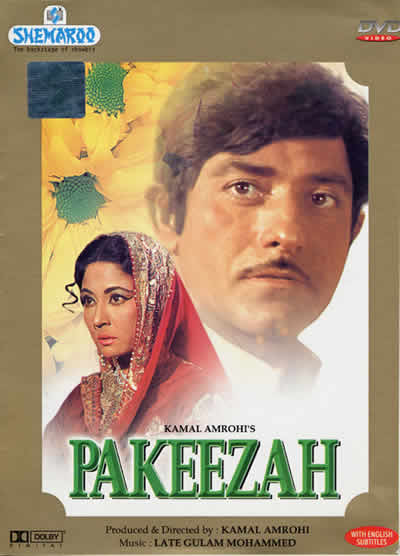

[Two DVDs of this important film have been marketed. That distributed by the India-based company Shemaroo (right, above) is much superior in quality and includes scenes deleted (without explanation) from the other version.]