PROFESSOR

(1962; Hindi; running time not available)

Directed by Lekh Tandon

Produced by F. C. Mehra; Story: Shashi Bhushan; Screenplay and dialogues: Abrar Alvi; Lyrics: Hasrat, Shailendra; Music: Shanker, Jaikishan; Cinematography: Dwarka Divecha

Shammi Kapoor (b. 1936; youngest son of Prithviraj Kapoor and brother of Raj and Shashi) is widely credited with having brought a new kind of hero, and a new libidinal regime, to the Hindi screen through his 1961 breakthrough hit JUNGLEE (“wild one”). In contrast to the eager but nervous and ultimately restrained romancers played by his elder brothers, Shammi (perhaps unconsciously drawing on the folk cliché of the amorous and restless youngest son; cf. Krishna) created a self-assured seducer, now coifed à la Elvis and clad à la Carnaby Street, whose aggressive sexuality, barely contained by the artifices of plot, spews out (so to speak) in body language, especially during song and dance sequences. This film (which also boasts an appealing Shanker-Jaikishan score and lovely footage of the Darjeeling Himalayas by Dwarka Divecha, who would later shoot SHOLAY) serves as a further vehicle for this persona, and for a surprisingly complex reflection on eros and its regulation, within the (modest) confines of the Indianization of the “sexual revolution.”

Shammi plays Pritam Khanna, an unemployed university graduate desperate for work. In contrast, however, to the visible grubbiness and disaffection of the un- or underemployed heroes of some 1950s films (cf. Vijay in PYAASA, Raj in SHRI 420), Pritam’s economic blues, framed within a comfortably bourgeois mise-en-scène and draped in a trendy wardrobe, are never more than a pretext for inserting him where the plot wants him to be: into a posh household full of sexually-repressed women. In the opening scene, a suited and goateed academic mentor (we never learn of what subject, but may assume that it is literary criticism, due to the gentlemen’s evident fondness for tropes) announces that Pritam’s sole possibility for employment—as tutor in the household of one Sita Devi, a wealthy woman in Darjeeling—has evaporated due to the employer’s insistence on “a man over fifty.” Returning home, Pritam learns that his adored and adoring mother (Protima Devi), whose white, patched sari tells us that she is a widow and who evidently has no other children, has been suffering from (but concealing) tuberculosis. When the doctor solemnly announces that Mother’s sole hope for recovery is to go for treatment to an expensive Himalayan sanatorium, Pritam resolves on an elaborate impersonation in order to score the well-paying Darjeeling job. Donning a graying wig, gold-rimmed spectacles, and false beard, clad in a nondescript frock coat and cap, and walking slightly bent and with the aid of a cane, he transforms himself into the requisite “Professor” and heads for the hills.

|

More tropes await him, for the Himalayas have long been associated, in Indian popular imagination, with eros, manifest both in the (supposedly) more forward sexual agency of ethnic hill women, and in the exhilarating and beautiful natural environment, remote from lowland urban society and its values, which facilitates romantic encounters (and is a stock setting for lovesongs, even when their framing films lack a mountain milieu).

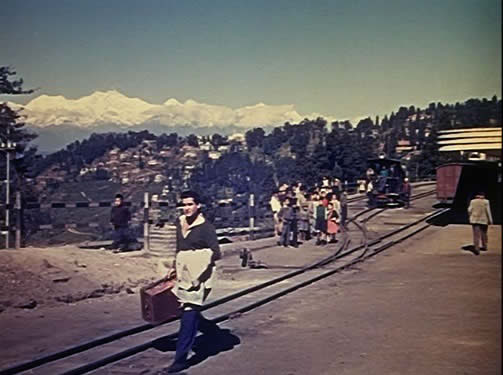

Reaching Darjeeling by the famous “toy train” (a blue-painted narrow-gauge railway), Pritam is greeted by folk musicians and dancers who perform the film’s first song, Koi aayega (“Someone will come”), against a backdrop of dazzling snowpeaks. Or rather, they serve as chorus line for an as-yet-unidentified but clearly non-local girl, whose smart toreador pants and blouse miraculously morph into ethnic “hill” regalia when she passes behind a bush, and who coyly sings of her blossoming sexuality and anticipation of a handsome stranger’s arrival (she has, in fact, already spotted Pritam on the path).

Pritam’s arrival at the palatial home of his employer occasions a bit of humorous intertextuality, for the silence of its columned main salon is suddenly shattered by the cry of “Yahoo!,” the beginning of the title song from Junglee and subsequently Shammi’s trademark, here presented as a phonograph recording being enjoyed by Sita Devi’s charges: the young sons and adolescent daughters of her deceased brother and his wife (who, we soon learn, were killed in a plane crash six months before); the arrival of the aunt’s car puts a stop to this merriment, however. For Sita Devi Verma (Lalita Pawar), clad in a policewoman-like khaki sari and high-buttoned long-sleeved blouse, is a harsh mistress of the household, as well as (apparently) the successful manager of a business and real estate empire. She is hated by her college-going nieces, Nina (Kalpana), and Rita (Praveen Choudhary)—the coquettish singers of the opening song—who call her ajallaad (torturer, harsh or merciless person; the subtitles render it “dictator”) behind her back, and later, when they become bold enough, to her face.

Since “Prof. Khanna” is to home-school the boys and then tutor the girls in Sanskrit when they return from college, he too is despised, and the young women repeatedly contrive pranks to provoke his dismissal by their suspicious and hot-tempered “Aunty.” Each time, however, Pritam manages to manipulate the situation so as to salvage his employment, meanwhile learning the ways of this dysfunctional wasps-nest of a mansion. |

|

|

|

Taunted by the girls, especially by the high-spirited elder Nina (through the song Yeh umar hai, “This is the age [of youthful passion],” in which she and her girlfriends describe their amorous longings, and the Professor protests that he, too, was once young and ardent), Pritam decides to get back at them by contriving to make Nina fall in love with him—in his undisguised form, but with the assumed identity of the Professor’s young nephew. This requires a lot of quick costume and makeup changes as well as several songs in which he comes on strong in characteristic Shammi style (the duets Main chali, “I am going,” and Aye gulbadan, “O rose-faced one [you are the fragrance of flowers and prick of thorns; seeing you my heart fears that I might fall in love with someone today]”); but the result is that both girl (first) and boy (later, succumbing to his own designs) are struck by love-god Kamadeva’s arrows amidst the terraced flower beds and tea gardens of the Darjeeling hills.

But enroute to a predictable romantic denouement for the two principals, there are some interesting digressions involving supporting characters. Younger sister Rita falls in love with a rich young college boy named Ramesh (Salim); rebelling (as the Professor had predicted) against her aunt’s strictness, she “goes too far” with him and winds up pregnant, even as Ramesh prepares to marry another girl chosen by his father. The Professor’s timely intervention to save the desperate Rita’s life and honor (and here the film suggests that premarital sex is okay as long as marriage follows) assists him in his own project of winning, as Pritam, Nina’s hand.

But still more interesting is the portrayal of his developing relationship, as aged Professor, to the girl’s dreaded Aunty, in a series of scenes in which both Shammi and Lalita Pawar give the film’s most creditable and intriguing performances. Pritam’s falsely-assumed age seems to have brought with it not only stereotypic comic mannerisms (squinting through his spectacles, moving his jaw as if chewing paan, etc.) but a certain wisdom regarding human character and motivation. Though we never actually see him teaching his young charges, he responds to them with avuncular understanding and soon becomes a buffer between them and their dictatorial aunt.

With the latter, his initial terror of her wrath (and of losing his hard-won employment) gradually yields to the insight that her harsh exterior conceals a tender but frustrated heart, and he is even able to frankly tell her this. She responds with slowly increasing warmth, ultimately confessing her love for the Professor, and indeed proposing marriage between them. Though viewers understand this to be an impossible dream, the actors succeed in projecting an odd but appealing couple whose union seems plausible and even desirable; indeed, Shammi appears (to this viewer at least) a good deal more interesting as a romantically-challenged fifty-something than as India’s “Elvis.”

As for Sita Devi, on the surface, the film’s conventionally sexist ideology explains her stentorian harshness as the result of sexual frustration and the assumption of an improper (i.e., masculine) role—and thus, this confident businesswoman who sits behind a big desk and successfully manages her wealth becomes, as she warms to the Professor, unable to act without his guidance (as when she flies him to Bombay to assist her in a legal matter), and increasingly preoccupied with her appearance, dyeing her hair, shifting to sleeveless sari blouses, and piling on jewelry. Yet Pawar’s sensitive portrayal gives sympathetic nuance to this cliché, creating a character who is likewise of considerably more substance than her preening nymphet nieces. |

Of course, the old aunt’s awakened desire must be sacrificed in the end, and the film accomplishes this through a heavyhanded (yet revealing) psychic transformation, therapeutically facilitated by Pritam, in which both her eros and her anger metamorphose into maternal love, thus rendering her (in Bombay cinematic ideology) a definitively non-erotic being. She can thus join the other asexual seniors—Pritam’s recovered mother, and the pudgy father of the cad Ramesh—in limply waving goodbye to two pairs of happy newlyweds, bound for the erotic delights of a double honeymoon in (presumably, and where else?) the hills.

[The Bollywood Entertainment DVD of PROFESSOR features a good quality print of the film, and offers serviceable subtitles for both dialog and songs.]