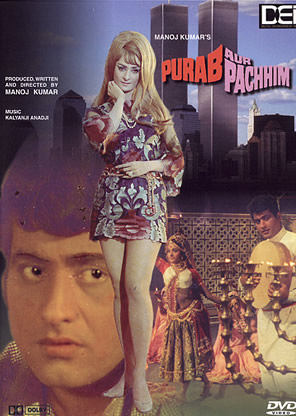

PURAB AUR PACHHIM ("East and West")

1970, color, Hindi, 175 min.

Directed by Manoj Kumar. Music by Kalyanji-Anandji.

The theme of the foreign-resident Indian, and of the cultural and moral dislocation that living "across the black waters" can induce in him (and still more in her), has been mined for both comedy and tragedy since the early days of Indian cinema (e.g., the 1921 silent film BILET PHERAT, or "England Returned"). It has remained a locus for exploration of such enduring Bollywood themes as the allure and threat of the West, and the nature and strength of Indian national identity — as well as a source of exotic glamour and erotic spectacle. Manoj Kumar's wildly excessive film is a classic sendup of all of these themes.

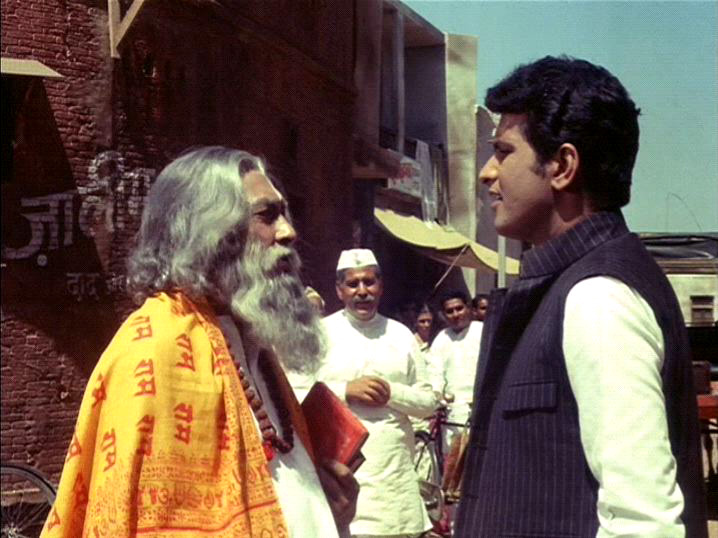

The complex storyline spans three generations of two families from Allahabad, a cultural center of eastern Uttar Pradesh. A prologue in black and white, set during the Independence struggle and shot to resemble newsreel footage, introduces Guruji, a venerable priest, and his son Harnam (Pran), a Westernized babu. When their neighbor Om, a freedom fighter with a price on his head, secretly comes home to visit his pregnant wife, Ganga, Harnam informs on him, leading to his murder by British police. Amidst a flood, Om’s grieving widow gives birth to a son whom she names Bharat (Hindi for "India").

Harnam soon flees to England with his reward money and his own infant son Omkar, abandoning his (likewise pregnant) wife Kaushalya, who gives birth to a daughter, Gopi. When the Brits burn Ganga's home, Guruji takes her in, raising both Gopi and Bharat as his grandchildren. B&W yields to florid color as the Union Jack is replaced by the Tricolor on August 15th, 1947, and we leap forward several decades to find the young adult Bharat (Manoj Kumar) being invited to England by his father's friend Sharma, who had settled there long ago.

Because the West now possesses the material magic of "science" and the two fatherless families need money, Bharat reluctantly agrees to leave, taking with him Guruji's blessing and a copy of the Gita. At London airport, he meets the avuncular Sharma, who has forgotten Indian ways (though later we will discover that he treasures a collection of K. L. Saigal records, a sure sign that his heart remains Hindustani), and his wife and children, who have never known them. Mrs. Sharma is a hairsprayed harpy, herself raised in England of Indian parents (to explain her fluent if intermittent Hindi), who chainsmokes and calls her husband "Darling."

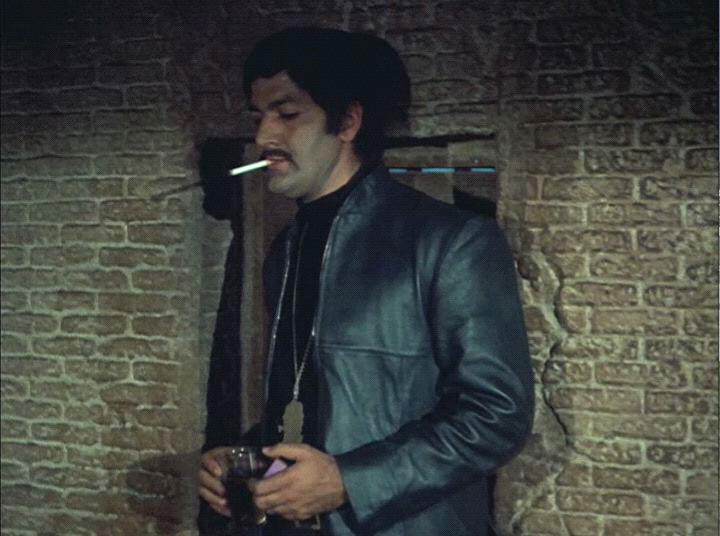

Their son, who calls himself "Orphan," is an aging flowerchild with terminal cultural confusion, and their daughter, Preeti (Saira Banu) a miniskirted, dyed-blonde bombshell, who shares her mother's addictions to cigarettes and booze. That she will fall in love with the chaste, self-confident Bharat is a foregone conclusion, but viewers can anticipate the delights of seeing how the film will negotiate this tricky multicultural affair.

They will not be disappointed. If Stanley Kubrick had hailed from provincial North India, he might have conjured up something like the Clockwork Mango world of Kumar's London — a titillating dystopia in the thrall of the psychedelic and sexual revolutions and Carnaby Street fashion fetishism, where deracinated Indians drown in liquor while ogling at miniskirted, go-go dancing blondes. Kumar lets his camera go wherever his eye would like to, making it an agitated, voyeuristic proboscis that also functions (via every cinematic technique available on his budget) as a spectatorial cuisinart that slices, whips, and purees reality. He makes marvelous use of reflecting surfaces: rivers, windows, mirrors, car doors, and of mind-boggling sets such as the "India Club" in London, where suited and booted NRIs gather to down scotch below portraits of Gandhi and Nehru amidst bordello decor AND three (count 'em!) revolving seating areas — an invocation of the whirling chakkar ("circle," but also "rat race") in which they reside. This is but one of a baroque cavalcade of scenes that includes a floating disco club on the Thames, a dog racetrack, the London Playboy club, and Oxford University (where a Hindi lovesong is rendered amid the cloistered lawns and deer of Magdalen College). Like Smirnoff, Kumar leaves you breathless, and his inventive incorporation of the cultural realia of late-‘60s London — Hare Krishnas chanting on the streets, pudgy working-class families strolling along the Thames, and the gesticulating employees of the greyhound track — suggests the satiric vision of a manic Third World ethnographer on acid. Eight strong songs include an amazing raga-ization of "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" (featuring Rajasthani-style marionettes that transform into the culturally-unstrung human characters), the rousingly patriotic Bharat ka rehne wala ("[I am] a son of India"), and the quintessential filmi bhajan (hymn) Jai jagdish hare ("Victory to Hari, Lord of the World"), which has become an anthem of transnational Hindutva.

Through its temporal and spatial scope, the film sagely suggests that the struggle for Indian "independence" did not end in 1947, but must be waged continuously in the market-driven world of postcolonial "brain drains," diasporas, and transnational (but West-centered) capital.

The ultimate threat is that the alienated NRI will (like the leather-suited Omkar) turn parricide and slay (or forget) his own parent culture. The film epitomizes the burden that diasporic society places on women as bearers of tradition, and its intense nationalism allows no hint that the West might offer Indians anything besides money, sex, and science — it’s ultimate goal is to Bring the Boys Home. Yet although predictably sexist and jingoist in its surface message, the film is more complex on the level of characterization: there are bad Indians like Harnam and Omkar, and good Westerners like Christina, who renounces her Indian fiancé when she learns from Bharat that he has an abandoned desi wife and child. There is also Francis, a French hippie pal of Orphan, who sacrifices his life to save Bharat in a club brawl and then dies requesting, "Pour l'amour de Dieu....votre chanson" (i.e., the Gandhian anthem Raghupati Raghava Raja Ram), while cradled in Bharat and Orphan’s arms in an amazing intercultural pieta.

Moreover, the NRI heroine, despite her steady diet of scotch and cigarettes, is still an Indian girl at heart, and ultimately redeemable. In its extravagance and wide-ranging vision, the film anticipates some of the innovative transnational interventions of the '90s, such as the British Asian artfilm BHAJI ON THE BEACH (which includes a fantasy sequence spoofing Saira Banu's character) and the Bollywood blockbuster DILWALE DULHANIYA LE JAYENGE -- in both of which NRI life in England is more frankly celebrated.

[The DEI DVD of this film is of good quality, though songs are unsubtitled. Despite its cover art, however, Kumar's film has absolutely nothing to do with New York City or with the World Trade Center (which had not even been built when the film was made!).]