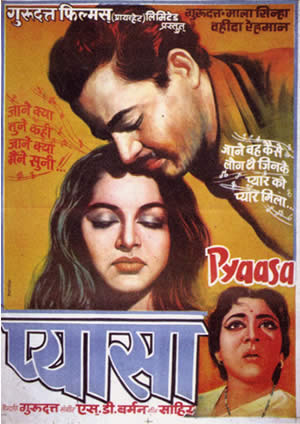

PYAASA

(1957), Hindi, 139 minutes

Directed by Guru Dutt. Music: S. D. Burman Lyrics: Sahir Ludhianvi

Playback Singers: Geeta Dutt, Mohammed Rafi, Hemant Kumar (aka Hemanta Kumar Mukherjee)

Cinematography: V. K. Murthy

(notes by Corey Creekmur, Department of Cinema and Comparative Literature, University of Iowa)

Pyaasa ("The Thirster") represents a high point in Indian cinema that, along with Mother India (also 1957) and major films by Raj Kapoor and Bimal Roy, confirms the 1950s as Hindi cinema's golden age. In his seventh film as a director, Guru Dutt -- taking a role originally intended for Dilip Kumar, who rejected it as too similar to his 1955 Devdas -- established his definitive screen personification as the anguished poet Vijay, whose artistic efforts are only appreciated by his loyal mother, his early but eventually materialistic college girlfriend Meena (Mala Sinha), his comical pal the masseuse Abdul Sattar (Johnny Walker), and, most profoundly, the young prostitute Gulab (Waheeda Rehman, who had premiered in Guru Dutt's production C.I.D. the previous year). Vijay's sensitivity and the world's indifference are established in a prologue depicting Vijay composing a poem in nature as he watches a bee flitting from flower to flower; suddenly, the bee is crushed by a passing stranger, the first in a series of innocents trodden under cruel heels throughout the film. Thrown out of his home by his coarse brothers, who have sold his poems as scrap paper, Vijay encounters Gulab singing one of the poems (Ho lakh musibat rasten men) she has learned from the papers purchased from the junk dealer. Flirting with Vijay as a potential customer, but rejecting him when he is found to be penniless, Gulab discovers that this "worthless" man is the poet whose work has so enchanted her. (Later, when Meena asks how a gentleman like Vijay could come to know a woman like Gulab, the latter quietly and wisely replies, "Saubhaagya se" [through good fortune]). Meanwhile, Vijay begins working for Meena's arrogant husband, the powerful publisher Mr. Ghosh (Rehman). Recalling his lost love, Vijay strains their marriage while his desire for recognition as a poet is continually thwarted. After he is sacked and considers suicide, he gives his coat to a beggar at a train yard; when an accident kills the beggar and injures Vijay, he is mistakenly pronounced dead, and Gulab succeeds in having his work published. When his volume of Urdu poetry, Parchhaiyan(Shadows), becomes a runaway hit, those who once scorned Vijay attempt to cash in on his "posthumous" fame. When Vijay is "resurrected" -- in full Christ-like pose -- at a public ceremony honoring his memory, he denounces the hypocrisy of a world that scorns living artists and profits from lies. In a conclusion added to the original, more downbeat version of the film (the shot of manuscript pages swirling around Vijay and Meena), Vijay and Gulab are reunited and leave Calcutta for parts unknown.

Pyaasa's carefully structured, melodramatic plot remains moving, and subtly links Vijay's pain to the independent nation's unsolved woes: the film proceeds through a series of ironic twists of fate and small but painfully dramatized failures: for instance, a rich Babu -- played in a cameo by the Bengali comic Tulsi Charaborty (who starred the same year in Satyajit Ray's first comedyParash Pathar) -- notes the irony of paying the educated Vijay for his services as a coolie before he slips him a counterfeit coin. Most disturbingly, Vijay can only watch and run away in despair when a dancing girl is forced to choose between entertaining drunken louts for small change and caring for her sick baby whose cries nevertheless cut through her upbeat music. However, the film's real triumph is found in its brilliant, consistent matching of style to theme. Dutt's regular cinematographer, the one-time violinist and jailed freedom fighter V. K. Murthy, provides some of Indian cinema's most breathtaking images in starkly contrasted black and white. The film's mastery of cinematic devices is especially demonstrated through Guru Dutt's genius for "picturization," which seamlessly coordinates music (by the legendary S. D. Burman), lyrics (by Urdu poet Sahir Ludhianvi), rhythmic editing, stark lighting, and fluid camera movement. For instance, when Vijay, working as a servant at Mr. Ghosh's snooty literary soiree, sings one of his poems (Jaane woh kaise), a pattern of forward and reverse tracking shots, pushing and pulling, back and forth, underlines the persistent desire and unbridgeable distance that now defines the poet's relationship to Meena, his former but shallow lover. A restless and wary camera also draws a drunken Vijay along dimly lit backstreets as he laments India's persistent exploitation of the downtrodden in the powerful song Jinhe naaz hai bind par who kahan hain. The film's final song, Yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaaye to kya hai elevates the film to an astonishing musical and dramatic crescendo, as slight head movements by all the major characters in the film match rising musical figures as Dutt cuts rhythmically among their close-ups. As the song builds from a whisper to a scream, Mohammed Rafi's steady voice breaks as Vijay's supposed admirers mutate into a rioting mob: the sequence provides a textbook example of how a filmmaker can wed the visual and sound elements of cinema to a storyline in the construction of powerful emotional meaning.

Although the film constructs a distinct vision that would characterize Dutt's remaining films -- especially the explicitly autobiographical Kaagaz ke Phool (1959), about a failed film director -- it's interesting to speculate on Dutt's possible influences when making Pyaasa: at least one song sequence (Hum aapke aankhon men), set in a cloud-covered dreamworld and hinting at Guru Dutt's origins as a dancer, appears to pay a modest homage to the famous dream sequence of Raj Kapoor's Awara (1951). More often the film -- especially its final rally for a constructed hero that escalates into a riot -- suggests Frank Capra's similarly bleak Meet John Doe (1941), and a late scene between the unscrupulous publisher Mr. Ghosh and Meena at their breakfast table surely alludes to Citizen Kane (1941). (In Welles' film, the famous "breakfast montage" ends as the first Mrs. Kane silently reads a copy of her husband's rival newspaper; in Pyaasa, Meena holds up an issue of Life magazine with a crucified Christ on the cover.) The film's consistently rich black and white photography suggests not so much American film noir of the 1950s, but its gloomy precedents in French poetic realist works like Carne's Le Jour Se Leve (1939) or Quai des Brumes (1938), which paved the way not only for dark American crime films, but for the existential artist-outsiders who would be Vijay's European soulmates following World War II.

For additional reading: Nasreen Munni Kabir, Guru Dutt: a life in cinema (Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). This sensitive tribute to Guru Dutt contains a fascinating chapter on Pyaasa, including the reminiscences of several close associates of the director.