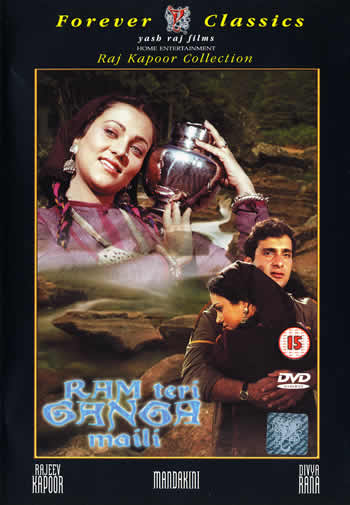

RAM TERI GANGA MAILI

(“God/Ram, your Ganga [Ganges] is tainted”)

1985, Hindi, about 170 minutes

Directed by Raj Kapoor

Produced by Randhir Kapoor for R. K. Films

Story: Raj Kapoor; Screenplay: K. K. Singh, Jyoti Swaroop, V. P. Sathe; Dialogue: K. K. Singh; Lyrics: Ravindra Jain, Hasrat Jaipuri, Ameer Qazalbash; Music: Ravindra Jain; Choreography: Suresh Bhatt; Art direction: Suresh Sawant; Cinematography: Radhu Karmakar

The last film that director Kapoor completed before his death in 1988 became a smash hit that heartily reconfirmed, after several lukewarm releases, his cherished epithet of “the Great Showman.” It is in fact in the grand Kapoor tradition: an ingenious and epic-scale allegory that synthesizes classical and mythic narrative, soft-core political and social commentary (here condemning the corruption of politicians and capitalists and championing the nascent environmental initiatives of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi), and audacious display of the female anatomy. Broadly speaking, the narrative recapitulates the Shakuntala story—that first appeared in the epic Mahabharata in perhaps the 3rd or 2nd century BCE and then was reworked, some six hundred years later, by the poet Kalidasa into the most famous of all Sanskrit dramas. Since the heroine of this story (after an ordeal that will be summarized below) became recognized as the mother of the dynast Bharata, whose name is reflected in the official, post-Independence name for “India” (Bhaarat, or “the [land of the] descendants of Bharata”), this tale is as portentous as it is popular.

But the film additionally alludes to another Mahabharata motif: that of a human prince’s union with a river goddess (as in King Shantanu’s marriage to Ganga incarnate), as well as to the myth of the divine river’s “descent” to the human realm, now superimposed onto mundane space to follow her meandering course over the north Indian plains to the Bay of Bengal. This permits the film to offer both a spectacular travelogue and an auspicious visual pilgrimage to some of north India’s most revered Hindu sites—from the source of the Ganga at the Gaumukh glacier, near the Tibetan border, to her great pilgrimage center at Banaras/Varanasi, to her merger with the Indian Ocean at Ganga Sagar, an island off the Bengal coast. As if this were not enough, motifs and themes from the Ramayana and from the life story of Krishna and his medieval poet-devotee, the Rajput princess Mira, are additionally worked in.

Ethnic ontogeny, national geography, Hindu mythology, and the feminization and divinization of land and nature thus all converge in the film’s blue-eyed Himalayan heroine, Ganga (played by Kapoor’s ingénue discovery Mandakini, whose stage name evokes another sacred river)—who shoulders this heavy symbolic burden, above her ample cleavage, as jauntily as she does the jug of ganga-jal (Ganges water) she carries in a famous scene early in the film. Like her epic prototypes, this divine forest-girl meets and falls for a city-boy and contracts an informal marriage with him—and then (so to speak) it is all downhill from there.

Some background concerning the Shakuntala story: One of the most ubiquitous tropes of classical Sanskrit narrative is of a prince, emblematic of masculinity, urbanity, and indeed human culture, who strays into the wilderness (usually while hunting deer) and there encounters a mysterious, semi-divine woman, symbolic of the fertility and protean power of nature, with whom he falls in love and who fatefully alters the course of his life. Shakuntala’s birth is itself the outcome of a brief liaison between a celestial courtesan (apsara) and a world-renouncing king, and she is raised in a forest hermitage where (like a Walt Disney heroine) she fondles tame deer and talks to birds and flowers. The virile King Dushyanta, out for a hunt, comes upon her and convinces her, with some difficulty, to enter into an informal “marriage” with him, promising to legitimize their union and send for her after he returns to his capital. In fact, the Mahabharata (with its characteristically astute and dark vision of realpolitik) makes clear that the king has no such intention, and merely intends to enjoy a one-night-stand with a naïve rustic belle. However, in Kalidasa’s better known version (possibly produced under the patronage of the Gupta kings), both Shakuntala and her royal lover fall victim to the power of a curse that causes her to lose the signet ring he gave her as a love token, and him to suffer total amnesia regarding the affair.

Kalidasa’s king-hero is thus exonerated of guilt for abandoning the heroine (and Raj Kapoor will likewise favor the latter approach, substituting a grandmotherly heart-attack and resultant family crisis for the loss of the ring). In any case, the lovesick Shakuntala becomes pregnant and gives birth to the hero’s son, and then—after enough time has elapsed to make her forest-dwelling neighbors wonder why no one has come for her—makes her own way to the royal city to present the boy to the king. In the story’s most powerful scene, the latter denounces her (in theMahabharata, Dushyanta knowingly lies, ostensibly to protect his reputation and lineage against the paternity suit of a possibly “loose” woman, but in the Sanskrit drama he of course literally does not remember who she is) and Shakuntala suffers bitter humiliation, yet offers a spirited and heartfelt defense of her claim. Both versions direct the audience’s sympathy toward the woman who has been wronged, and ultimately rely on a deus ex machina to bring the erring (or amnesiac) king to his senses—whereupon the little family is happily reunited and Shakuntala’s son, the demi-divine Bharata, becomes heir to the throne. Kapoor’s film substitutes a weak hero for an erring one and introduces parental and family complications that further exonerate him, and it situates most of its heroine’s humiliation during her long journey to the metropolis.

RAM TERI GANGA MAILI opens with a brief prologue depicting a political rally on the banks of the Hooghly (the name of the Ganga’s channel that flows through Calcutta), ostensibly to protest the pollution of the river, but in fact (as we learn immediately after the credits) as a grab for power by the corrupted party boss Bhagwat Chaudhury (Raza Murad) and his industrialist backer Jeeva Sahai (Kulbhushan Kharbanda), to whom he has promised a license to build another polluting factory.

The credit sequence alternates scenes of the pristine river of the Himalayas with her debased form on the plains, graphically showing (in newsreel-like footage) her pollution with human corpses and raw sewage, while the bhajan-style title song intones a verse (among others) that alludes to Kapoor’s own previous oeuvre: his JIS DESH MEIN GANGA BEHTI HAI (“the land in which Ganga flows,” 1960):

He who has worshiped Ganga with head humbly bowed,

And who has sung the praise of the land in which she flows,

He too now must come forward to say, ‘God, your Ganga is tainted.

While magnate Sahai celebrates the ruthless Chaudhury’s election as party president and plots a marital alliance between Chaudhury’s daughter Radha (Divya Rana) and his own dreamily idealistic son Narendra (or “Naren” for short; Rajiv Kapoor), the latter ponders the writings of Hindu reformer Swami Vivekananda (whose given name was also Narendra), and dreams of a college trip to the source of the Ganga, to discover if the river is truly pristine upstream, far from the corruption of Calcutta. Though his father refuses him permission to go, Naren obtains it through the intervention of his pious, wheelchair bound grandmother (Sushma Seth), who gives him a metal urn and begs him to “bring Ganga back” to her. Naren’s cause is also championed by his maternal uncle (mausa) Kunj Bihari (Saeed Jaffrey), an artistic bon vivant who frequents courtesan houses and who quotes a verse of Muhammad Iqbal concerning Ganga, but who outfits Naren with a Swiss hat and suede jacket for his mountain idyll.

Once in the Himalayas, Naren’s group finds the road to Gangotri blocked by landslides and settles into a comfortable holiday camp serviced by local mountain folk. It is while ecstatically roaming the hills nearby that Naren has his first encounter with Ganga-the-girl, in a scene brilliantly staged to evoke its mythic resonances—she is first experienced through her tinkling laughter, and then rises, yakshi-like, from a field of wildflowers to announce “I am Ganga.” It is, of course, love-at-first-darshan for both young people, and their bond is cemented when Naren saves Ganga from an attempted rape by one of the college lads, and then accompanies her on a walking pilgrimage to the river’s source. There is truly breathtaking scenery enroute, and also accompanying Ganga’s first song (that establishes her as both innocent and seductive), Tujhe bulaye yeh meri bahen (“my arms call to you”).

The voyeuristic side of Kapoor’s reputation as “Showman” rested in part on his willingness to repeatedly push the envelope on what government censors would permit filmmakers to “show” on the screen: from Nargis’ bathing suit in AWARA (1951), to Dimple Kapadia’s bikini in BOBBY (1973), to Zeenat Aman’s blouseless mini-sari in SATYAM SHIVAM SUNDARAM (1978). The equivalently scandalous (and doubtless most replayed) scene here is Mandakini’s bath in a waterfall while singing Tujhe bulaye…, the refrain of which calls out “Aa jaa” (“Come to me,”)—her gauzy sari rendered translucent by the water to offer, in effect, a full frontal display of the young actress’ generous charms.

Pre-marital sex in Hindi cinema, at least until recently, generally adhered to two rules: (1) the encounter had to be understood by the couple as a genuine and committed “marriage,” suggested by evocations of nuptial ritual (see, e.g., the prototypical scene in ARADHANA, 1969), and (2) even a single night’s contact invariably resulted in pregnancy that, moreover, produced a male offspring. In RAM TERI GANGA MAILI, the pretext for Naren and Ganga’s abrupt union is the supposed “mountain custom” of girls being allowed to choose their own spouses during an annual full-moon festival (represented by the song Sun Sahiba sun, “Listen, Beloved [I have chosen you; will you choose me?]”), as well as the pressure exerted by another local suitor. In a dramatic scene, Ganga leads Naren to a ruined temple that has been adorned as a nuptial chamber, while outside her stalwart brother Karan Singh (played by Hindi-speaking Indo-American actor Tom Alter in a rare non-Anglo role) fights off the jilted fiancé and his minions, ultimately sacrificing his life for his sister’s happiness.

Alas, that happiness is not destined to last long. After a single blissful night, Naren returns to Calcutta with his school group, promising to return soon to fetch Ganga. Instead, he finds the house adorned for his own engagement party—to Chaudhury’s daughter Radha—and when he tries to tell his grandmother that he is already married, she suffers a heart attack. Naren is no irresponsible Dushyanta, however. Though stricken with guilt over his grandmother’s death and severely beaten by his father who blames him for it, Naren attempts to escape to rejoin Ganga, but is apprehended in Rishikesh by police alerted by the evil Chaudhury, and brought back to Calcutta a virtual prisoner. Plans for his marriage to Radha proceed. Eventually, he confides in his uncle Kunj Bihari, who makes a second, unsuccessful attempt to retrieve Ganga.

The mise-en-scène alternates between Naren’s trials and the advancement of Ganga’s pregnancy against the backdrop of changing seasons in the Himalayas. Among falling leaves (and while Naren languishes in a police lockup in Rishikesh), the very-pregnant Ganga sings a long-distance duet with him (Yaara O yaara, “Beloved, O beloved”); she gives birth to their son, helped by a midwife and the friendly village postmaster, as snow falls on the hills. Yet when Naren still fails to appear by the next spring (and a misdirected letter from Radha reveals details of the planned marriage in Calcutta), the distraught Ganga resolves to go to Calcutta. She intends to make no claim on Naren (who she thinks has spurned her for Radha), but only wants him to accept their son.

Ganga’s trials now take a more demeaning dimension. Tragically missing Kunj Bihari at the Rishikesh bus stand, the innocent girl (who knows only that Calcutta is the place “where the Ganga ends”) is waylaid by a succession of exploiters: the madam of a cheap brothel in Rishikesh, a lecherous brahman priest, and finally a wily procurer for a higher-class kotha or courtesan house in Banaras, who is drawn by her beautiful voice. Though some viewers might wince at the film’s relentless depiction of the helpless vulnerability of a young mother lacking the “protection” of a male escort, the type of situations depicted, and the satire of exploitative north Indian types is, alas, not altogether hyperbolic (many prostitutes in Bombay and other cities are in fact said to be waylaid girls from the Himalayas), nor is Ganga entirely without agency: she fights back, attempts escape, and hurls shaming sarcasm at her abusers and would-be corrupters. Throughout this numbing “descent” of Ganga-personified, there are ironic allusions to the sacral status of the river for which she is named, that reflect on the hypocrisy of formal religion (as when an elderly woman on a train refuses Ganga a sip of water for her infant, because it is precious Ganga-water obtained on a pilgrimage). Though Ganga increasingly sees herself, and is seen by others, as a “fallen” woman, the film is of course careful to maintain her technical chastity, and the “Bai” or courtesan to whom she is eventually apprenticed gives a speech clarifying that her girls are trained only for “singing and dancing,” and are not forced to “sell their bodies.” Nevertheless, after a remarkable dance performance in a pavilion on the bank of the holy river that reprieves the title song, now in Ganga’s plaintive voice, she is indeed sold—to a powerful and ruthless politician from Calcutta (Chaudhury, of course), thus paving the way for the film’s extraordinary climax, when Ganga (assisted by Uncle Kunj, who has finally located her) is brought to perform at Naren’s wedding to Radha. Kapoor pulls out all the stops during this dazzling sequence, juxtaposing a double entendre-laden bhajan (Ek Radha, ek Meera, “There is Radha, here is Meera [both love Shyam, but say, what is the difference between them?]”) with a series of seemingly irresolvable dharma-dilemmas, escalating dramatic speeches, and even a (somewhat) surprising ending.

As an ideological statement, the film displays all the status-quo-affirming warts characteristic of Kapoor’s work (and indeed of much of mainstream Hindi cinema): the ultimate reduction of social conflict to family squabbles that can be resolved through “love” and “faith,” and the combination of enlightened messages about women’s agency and honor with the relentless display of their bodies and the stereotyping of their social roles within an unquestioned patriarchal matrix. By positing no explicit connection between the villainous Sahai and Chaudhury’s corruption and the hyper-rich lifestyle enjoyed by their families, the narrative apparently seeks to divert resentment against an entire class toward a few “bad” individuals within it, and gives viewers license to relish the spectacle of Naren’s innocently conspicuous consumption of the fruits of dad’s ill-gotten gain (e.g., he sports a different mod outfit every day on the Gangotri trip). Yet like all of Kapoor’s best work—and I personally rank this film not far below AWARA and SHRI 420—it also presents a visual and textual richness that can support variant readings.

Though the sincere but ineffectual Naren finds a voice at the end, it is the performances of Saeed Jaffrey as Kunj Bihari—an old debauchee who refuses to be a hypocrite—and of Mandakini as Ganga—an innocent who is nevertheless discerning and capable of the most disarming forthrightness—that dominate the film. When the two finally meet, Bihari (plotting a way out of Ganga’s plight and alluding to Sita’s agni pariksha or “fire ordeal” in theRamayana) delivers the memorable line, “You have already been through a severe fire-test, daughter-in-law; it is now your Ram’s turn to be tested!” Amen.

[The Yash Raj Films DVD of RAM TERI GANGA MAILI is of superior quality and offers subtitles for songs as well as dialogs. Like all subtitles, these are sometimes off the mark (e.g., when the pregnant Ganga, patting her tummy, metaphorically sings, “I have put on the adornment of your love,” the subtitle pragmatically substitutes “I bear your child”), but they make this densely-coded film more accessible to non-Indian viewers. The film is also available from Shemaroo, Ltd., the company that holds the Indian rights to the Kapoor films; I have yet to see this version, however. Though rarely available in the US, Shemaroo DVDs sometimes offer vastly superior quality prints (e.g., of AWARA and SHRI 420) to those sold by Yash Raj—although they generally do not provide subtitles for songs.]