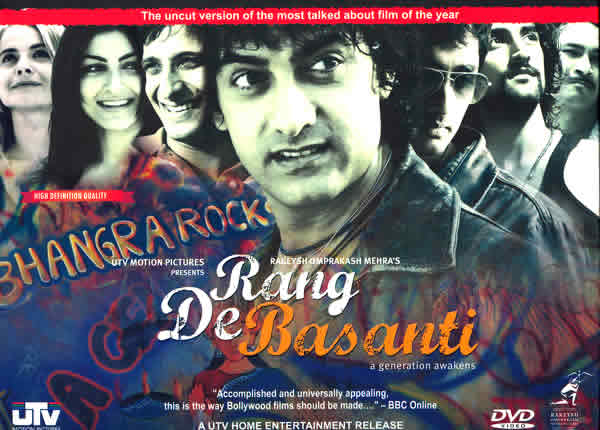

Rang De Basanti

(“The Color of Sacrifice”)

Directed by Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra

Produced by Ronnie Screwwala

Story and script: Kamlesh Pandey; Dialogue: Prasoon Joshi, Rensil D’Silva; Screenplay: Rensil D’Silva, Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra; Lyrics: Prasoon Joshi; Cinematogaraphy: Binod Pradhan; Music: A. R. Rahman

This complex and unsettling tale about the political awakening of a group of jaded urban youths became one of the most acclaimed and talked-about films of 2006 in India, as well as India’s entry in the US Academy Awards. In the best tradition of Bombay film, it is both innovative and conservative: a forward- and backward-looking meditation on two of the preoccupations of Hindi cinema: nationalism and filmmaking. Its fast-paced and visually arresting presentation belies a multi-layered storyline that assumes considerable background knowledge of twentieth-century Indian history. The story of the 1931 martyrdom of the young revolutionary and freedom fighter Bhagat Singh and his companions Rajguru, Sukhdev, and Chandrashekhar Azad—one of the hallowed legends of modern Indian history and itself the subject of a spate of recent films (see, e.g., THE LEGEND OF BHAGAT SINGH, 2002)—is again retold here, this time interwoven with a contemporary fable about radicalization and sacrifice. The two parallel narratives, one familiar and closed, the other emergent and unpredictable, come together through the eyes and lens of a fictional director making a film-within-a-film.

It is immediately suggestive of the unconventionality of certain aspects of Rang de Basanti (I will note the conventionality of others below) that the filmmaker is a young Englishwoman, Sue McKinley (Alice Patten), visiting India for the first time in order to make a TV documentary about the martyrs. She has a personal stake in this, for her screenplay is based on the diary of her grandfather, James McKinley, who was one of the wardens presiding over the young revolutionaries’ incarceration, torture, and execution. His cracked pocket watch, stopped at the moment of their death, is one of several talismans that open a window, in the color-saturated present, to the sepia-toned past, and his blonde, blue-eyed granddaughter, who has (we are told) taken night classes in Hindi for two years, is (again in the grand tradition of Indian epic) both the story’s narrator and one of its central characters.

An outsider-insider, she reverses the recent trend toward expatriate NRI heroes and heroines (who view the West through privileged Indian eyes) to invite Indian viewers to see themselves through foreign ones. That her gaze is discerning and not stereotyped, appreciative but not fawning, doubtless owes much to the scriptwriter and director, but also to Ms. Patten’s sensitive and endearing performance. Although, as a woman (and here the film shows a more conventional side) her role can only be to witness, from the sidelines, the central spectacle of male martyrdom, she is nevertheless (for Hindi cinema) a notably unconventional witness.

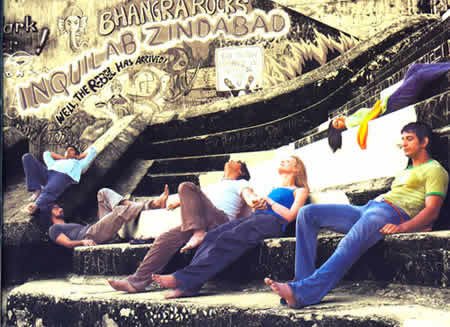

As the film begins, Sue’s dream of retelling the story of the anti-Raj revolutionaries is abruptly shattered when her BBC “World Vision” producers pull the budgetary plug on the project. Angry and disheartened, she goes to India anyway, where her would-be collaborator Sonia (Soha Ali Khan) cheerily announces that they will go ahead with the project despite the withdrawal of funding. (The small detail of how they will pull this off is, like a number of other improbables in the film, left to our willing-suspension-of-disbelief.) Settled into a posh flat in an “International Institute” at Delhi University (in fact, the set is the campus of the city’s impressive Habitat Centre), Sue begins casting her film, which is to feature an elaborate re-enactment of the revolutionaries’ decisive acts: the Kakori train robbery of 1925 to obtain money to purchase weapons; the fatal shooting of police officer J. P. Saunders in retaliation for the clubbing death, during a nonviolent protest in 1928, of elderly nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai; the April, 1929 detonation of a non-fatal bomb in the Delhi Central Assembly in order to call attention to their cause; and their subsequent imprisonment and execution. But Sue’s auditions yield only vapid and ludicrous wannabe actors — unable to put any oomph into freedom-struggle slogans like “Vande Mataram!” (“Hail to the Motherland!”) and (the preferred cry of the Leninist Bhagat Singh) “Inqilab Zindabad!” (“Long live the revolution!”) — until Sonia takes her to a different sort of “classroom” (Paathshala, also the film’s first song), a surreal cliffside amphitheatre where a gang of ultra-hip and not very studious college friends gather, hang, and party hard.

Like the village cricketers in Lagaan, this is a carefully-assembled microcosm of sub-ethnicities, including Karan Singhania (Siddarth), the son of a Sindhi Hindu millionaire, lanky Aslam (Kunal Kapoor), from a conservative Muslim family in Old Delhi, and two shorn Sikhs: the goofy Sukhi a.k.a. Sukhwinder Singh (Sharman Joshi), whose sole aim in life is to lose his virginity (evidently a difficult undertaking, for him), and a leather-jacketed biker whose proper name Daljeet Singh is similarly cropped to the coolly casual “DJ” (Aamir Khan). DJ is the nucleus of the group, and, despite having graduated years before, is loathe to leave it and enter the “real world” off-campus (evoking a phenomenon familiar enough to those who live in college towns, while also helping to explain actor Khan’s obvious age seniority to the others).

Reckless and energetic, DJ has (despite his tonsure) a shoulder tattooed with a large khanda, the Sikh sacred emblem, and is devoted in his way to his pious mom (Kiron Kher), who runs a roadside dhaba or open air Punjabi restaurant; in one sequence his family takes Sue and the others on a trip to Punjab that includes a pilgrimage to Amritsar's Golden Temple, the Sikh holy of holies (this sequence is accompanied by the moving song Ik Onkar, a rendition of the opening stanza of the Japuji, the first hymn of the Sikh scripture Guru Granth Sahib.)

At the group’s hangout, Sue also encounters another “type”: Laxman Pandey (Atul Kulkarni), a Brahman active in the student wing of a Hindu nationalist party that is never identified by name, but is clearly a stand-in for the BJP. A self-righteous true believer, Pandey leads his own gang of saffron-scarved thugs who bully and beat up students engaging in what he considers “immoral” and “foreign” pastimes, such as drinking parties or socializing with Muslims; he is, needless to say, a natural enemy of DJ and his apolitical pals.

It is Sue’s vision, of course, that will discern, in the graffitied “classroom’s” unlikely loafers, the perfect actors for her anticolonial passion play, and she will even succeed in inducing the fiery Pandey — the only one who actually knows much about the martyrs — to join the troupe. Once cast, her film begins to unfold as a series of dramatic inserts into the present-day narrative.

In an admirable cinematic move, these sometimes-abrupt cuts to a beautifully-realized early 20th century India are never precisely identified; they may be scenes from Sue’s (wished-for but unmakeable?) film, collective reveries, or true historical flashbacks revealing the reluctant collegiate actors as veiled avatars of the rebellious idealists of the past. These veils begin to lift after the Interval, however, through a secondary plot involving the most noble of their friends, the idealistic young airman Ajay Rathod (Madhavan), and their gradual uncovering of a scandal involving the Indian Air Force and a corrupt (and Hindu Nationalist) Minister of Defense. The scandal (which is based on a real one involving the alleged purchase of substandard replacement parts for Russian MIG fighter jets, leading to a high number of fatal accidents) causes the film’s two parallel narratives to coalesce toward a catastrophic denouement. Although the specifics of this coalescence may sometimes strain credulity (e.g., it is difficult to imagine the brutal beating, by riot police, of a group of middle-class Delhiites holding a peaceful candle-lit vigil near India Gate’s monument to the Unknown Jawan), the film’s relentless depiction of state-sponsored violence condoned by hypocritical politicians (a grim reality, certainly, for many poorer citizens, especially in rural areas) evidently struck a chord with Indian audiences. Indeed, its explicit depiction of young jeans-clad consumerist cynics morphing into Independence-era martyrs bears an implicit and chilling corollary message: that (as Bhagat Singh feared) the Indian state has now become a reincarnation, ruled by “Brown Sahibs,” of the repressive Raj that it once replaced. And despite the film’s effort to contextualize and soften its heroes’ desperate act, it imparts the further implicit message that, in the face of this irredeemable regime, violence may be the only reasonable response — rendering problematic the film’s subsequent enthusiastic invocation by young activists from a broad spectrum of political persuasions.

The visceral impact of Rang de Basanti is enhanced by a fine score (including the title song — a pulsing, patriotic anthem in Punjabi) by the versatile A. R. Rahman. The delivery of this score, though, is another of the film’s unconventional features, for (as in a handful of other recent Hindi films) there is no “playback singing” here. That is, the songs are presented non-diegetically, without the actors mouthing their lyrics, as mere “soundtrack” to the action. This is, of course, the Euro-American norm, separating ubiquitous cinematic dramas-with-music from the now-peculiar genre of the “film musical,” but it departs from some six decades of standard Bombay practice. The most obvious effect of its adoption is to give Rang de Basanti a “cooler” emotional tone, allowing the heroes to “move” to moving lyrics without themselves expressing them. Whether as hard-drinking nihilists or reluctant activists, the young heroes of “the classroom” are evidently too cool to sing their hearts out.

Yet despite this innovation, Rang de Basanti, with its elaborate plot structure and central motif of cyclical time, remains a characteristically self-reflexive Hindi film, even recapitulating the time-honored tropes of male dosti-unto-death (cf. SHOLAY), and of a wounded and comatose Mother India (regally rendered in a cameo by the great Waheeda Rehman) being reinvigorated by the sacrificial lifeblood of her sons (cf. AMAR AKBAR ANTHONY). Such hybridizing of “tradition” and “modernity” has always been a hallmark of Hindi cinema at its best, and director Mehra’s second film (after the uninspired but technically accomplished thriller Aks) easily deserves the success it has achieved.

[The UTV DVD of Rang de Basanti is of high image quality and offers effective subtitles for both dialogs and songs.]