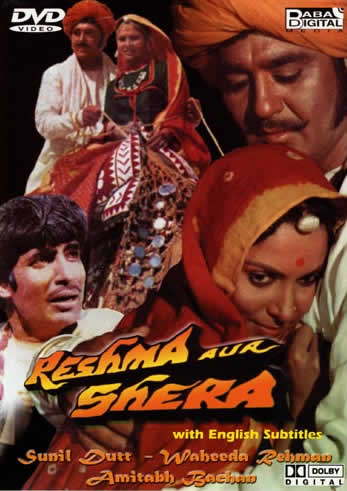

RESHMA AUR SHERA

(“Reshma and Shera,” Hindi, 1971, 140 minutes)

Produced and directed by Sunil Dutt

Story: Ali Raza; Music: Jai Dev; Lyrics: Balkavi Bairagi, Neeraj, Udhav; Cinematography: Ram Chandra

Equally bold visually and ideologically, this high budget but highly idiosyncratic film, shot in and around Jaisalmer, uses a conventional romantic narrative—a variant on Romeo and Juliet, here transposed to the realm of feuding Rajput clans—in the service of a decidedly unconventional message. It proved an expensive flop for producer, director, and star Sunil Dutt, and in retrospect, it is not hard to see why: for despite memorable songs by Jai Dev et. al., this is essentially an “art film” in disguise, and its hero, driven by a tragic destiny of Sophoclean dimensions, breaks any number of cultural and cinematic taboos. Its cinematography, capturing the stark dunes and intricate architecture of the Thar Desert, still looks good today, its rustic locations and crowds of authentically Rajasthani extras lend it, at times, almost the air of an ethnographic documentary, and its grimly against-the-grain story, which leaves viewers to ponder the human cost of machismo and patriarchal izzat (family or communal honor), seems more timely than ever. Waheeda Rehman gives a captivating performance as the heroine Reshma, and not-yet-superstar Amitabh Bachchan has a small but important role as the hero’s mute junior brother Chotu. Though a bit old for playing the romantic hero, Dutt offers a compelling performance as an initially Ashoka-like hero who has grown disillusioned with carnage and is veering toward a Gandhian path, but gets horribly derailed by revenge to become a tormented parricide and fratricide.

The Rajputs of the villages of Pochina and Karda are longtime rivals, and when the story opens, the family of the Chaudhury (headman) of Pochina is celebrating the murder of one of the five sons of Chaudhury Sagat Singh of Karda. The Pochina headman’s own (and only) son Gopal departs for an annual fair in honor of the patron goddess of Jaisalmer, accompanying his beautiful sister Reshma, who invokes Durga’s blessing for their safety. Meanwhile, Sagat Singh’s surviving sons Jagat, Vijay, and the mute Chotu leave for the fair with their elder brother Shera, who orders them to refrain from violence during the pilgrimage. At the fair—rendered in marvelously authentic detail, down to a peanut-vendor sporting the first transistor radio that the villagers have seen (the entranced Reshma calls it radio ka baccha, “the baby radio”)—Reshma and Shera’s eyes meet, and their love is nurtured by a wonderful (and very un-filmi)qawwali performance. When Shera’s brothers attack Gopal with swords, Shera intervenes and disarms them, furthering Reshma’s blossoming love for him. He begins to visit her by night, lighting a bonfire in the dunes outside her village and vowing to put an end to the enmity between their clans by paying his respects at Gopal’s forthcoming marriage. Yet the hatred of the senior Chaudhurys tragically aborts these plans, turning the wedding into a bloodbath, which then propels Shera on a horrific path of vengeance that can only be stopped by Reshma’s own dramatic act of self-sacrifice. Women stand tall in the film’s final segments, confirming Reshma’s earlier declaration that only they have been blessed by the Goddess to rebuild the world through acts of sacrifice.

Given the deliberate non-specificity of location in virtually every mainstream film about rural life (e.g. MOTHER INDIA, GUNGA-JUMNA, LAGAAN), Dutt’s determined focus on western Rajasthan is worth pondering. Visually it allows for stunning vistas of rippling dunes traversed by plodding camels, sandstone temples and palaces, and whitewashed huts adorned with intricate mirrorwork stucco; nothing here looks manufactured for the camera’s eye. But an ideological tinge to the location seems clear if the film’s appalling tragedy is read as an allegorical indictment of the forces that drive Hindu-Muslim communalism. Although historically, the Rajputs (“sons of kings”) may themselves be descended from Central Asian invaders of the 4th-6th centuries, they quickly assimilated to Sanskritic ideology. Acquiring Brahman-manufactured genealogies that linked them to the mythical solar and lunar dynasties of bygoneyugas, they became kshatriyas, exemplars of the ruling warrior caste that is closely allied with the sacerdotal Brahman elite. Locked in their own internecine vendettas of the sort accurately depicted in the film, they periodically fought, but also commonly allied with, Muslim invaders after 1200 C.E. Yet they acquired a reputation in later Indian historiography (in part due to the romantic and imperialist project of Colonel James Tod’s massive Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, published in 1829) as proto-Hindu nationalists, defending the soil of the Motherland with their code of death before dishonor. During the independence struggle, when direct criticism of the British regime was proscribed, the fight against “foreign tyranny” was allegorically projected backward into the Mughal period, and anti-Mughal Rajputs like Rana Pratap of Mewar became favored subjects of poster artists and speechmakers. He remains in the nationalist pantheon and is especially beloved of the ideologues of “Hindutva”—the more so since Rajasthan’s geographical location now poses its sons as guardians of the desert frontier that borders on Pakistan. By questioning—even mocking—the Rajput ethos as an ultimately destructive patriarchal obsession, Sunil Dutt (famously married to the Muslim actress Nargis who starred as MOTHER INDIA) thus attacks a sacred cow of Indian and especially Hindu nationalism, which feminizes the nation and valorizes male violence as necessary to defend “her” honor against culturally and politically threatening "outsiders"—a label easily applied to Indian Muslims by Hindu nationalists. In Dutt's film, Muslims play only a peripheral role and are shown (again authentically) as well-integrated into local society. Muslim qawwals (Sufi-style devotional singers) participate in the Goddess’ fair in Jaisalmer and their passionate singing occasions Shera’s first declaration of his love for Reshma. The lungi-clad villager Rehmat Khan (Amrish Puri) serves as friend and advisor to Shera’s family at key moments, and though initially endorsing the code of violent revenge, he is among the first to renounce it at the film’s end.

RESHMA AUR SHERA opens with a grandiose lecture, intoned by a basso narrator while its Devanagari text slowly scrolls by in saffron-colored letters, on the “heroic self-sacrifices” (balidan) of Indian women, a theme that is later visually echoed through images of the handprints of satis (Rajput widow-suicides) and of fiery conflagrations. The ponderous language seems to invoke the trope of MOTHER INDIA even as it appears to pre-impose a piously patriarchal interpretation that the unfolding story will tend to undercut. Perhaps this is an attempt to win friends and influence viewers by downplaying the film’s deeply subversive premise: that the much-vaunted “self-sacrifices” of Indian women, which it ostensibly salutes, are occasioned principally by the mess that their honor-obsessed and blinded men make of their own and others’ lives.

Addendum from Corey Creekmur:

In addition to the striking use of actual landscapes and locations, I would also point to the rich function of highly unconventional camera positions, and an overall organization through patterns of circular and fire motifs, as well as "rhymes" of key moments (e.g., Reshma intervening to stop two sacrifices by sword, and her two scenes before images of Durga: in each case, the early, "minor" incidents expand into major dramatic highlights later on). The odd camera positions seem at times to emphasize Reshma's stablity as the world spins around her: in fact she's in motion, but since the camera is fixed on her, the background seems to be in flux. The wonderful early scene with the temple bell is also edited to push the two characters awkwardly off-center in each shot, with the bell balancing the frame, so that the sequence is only "balanced" and dramatically concluded when the bell is rung. Overall the film seems to employ circles as both welcome enclosures (a ferris wheel, Reshma’s bangle) and as dangerously repetitive (the endless cycle of revenge); fire plays a similar role—the framing of the couple behind the bonfire suggests both purification and destruction, burning desire and self-immolation.

In addition, I was greatly impressed by the development of Reshma's character from giggling girl to erotic lover to defiant daughter to tragic heroine. (The confrontation of the goddess, near film’s end, was a stunning sequence!) Waheeda Rehman's face and body seem worlds apart from the beginning to the conclusion. Although Shera also goes through great psychological transformations, Sunil Dutt's performance seems less varied. It's eventually more his story than hers, but her character seemed richer and even more tragic to me, as she loses an innocence he never appears to have had.

[The Baba Digital DVD of RESHMA AUR SHERA is generally of good quality with adequate subtitles (though songs are unsubtitled). However, there are several abrupt cuts where portions of the film, which is listed as 158 minutes in the Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema, seem to have been lost, most notably during the attack on the Pochina marriage party. Though this is very unfortunate, enough survives of this gorgeously atypical film to reward viewing.]