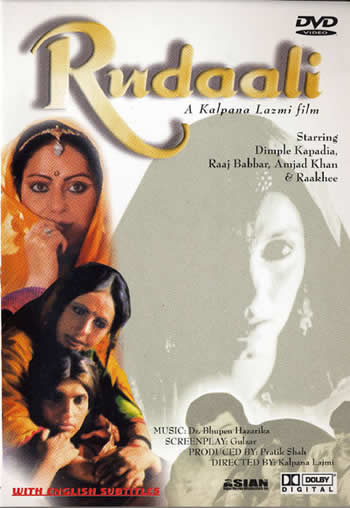

RUDAALI

(“the professional mourner”)

1992, Hindi, approx. 126 minutes

Directed by Kalpani Lajmi

Produced by Pratik Shah

Based on the short story “Rudaali” by Mahasweta Devi; Screenplay, Dialogue, and Lyrics: Gulzar; Music: Dr. Bhupen Hazarika; Choreography: Bhushan Lakhandari; Art Direction: Sameer Chanda; Cinematography: Santosh Sivan, Dharam Gulati

Underwritten by the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) and Doordarshan (Indian national television) as part of the Indian government’s controversial but ongoing effort to provide audiences with edifying alternatives to “Bollywood” entertainment, and based on a short story by famed Bengali author Mahasweta Devi—whose tales often focus on the travails of low-caste women—RUDAALI is an uncommon and arresting film. Shot mostly on location in the Jaisalmer region of western Rajasthan, it features authentic regional costumes and props, somewhat less authentic (but quite haunting) music, and two famous female stars, Dimple Kapadia and Rakhee Gulzar, cast in unusual and challenging roles—the central roles in this film that lacks male heroes. Indeed, the women it portrays cannot rely on men for either love or support. The film is unusual too in having a female director: Lajmi (who, incidentally, is a niece of Guru Dutt) was a longtime assistant to Shyam Benegal before she became a successful director of documentaries. RUDAALI was her second feature film.

The title refers to a custom in some parts of Rajasthan—where aristocratic women were long kept secluded and veiled—of hiring professional women mourners on the death of a male relative, a rudaali (pronounced “roo-dah-lee”—literally, a female “weeper”) to publicly express the grief that family members, constrained by their high social status, were not permitted to display—or at times, perhaps did not feel. Dressed in black and with unbound hair, a rudaali beat her breast, danced spasmodically, rolled on the ground, and shed copious tears while loudly praising the deceased and lamenting his demise; the ability to hire such a performer was a mark of social status. The film’s credits roll against a stylized backlit chorus of five such women, their faces concealed in shadow, dancing in unison on a surreal parquet floor that is (apparently) the film’s only soundstage set. The urgent drumming and orchestral music that accompanies their dance will recur periodically as an ominous motif throughout the story.

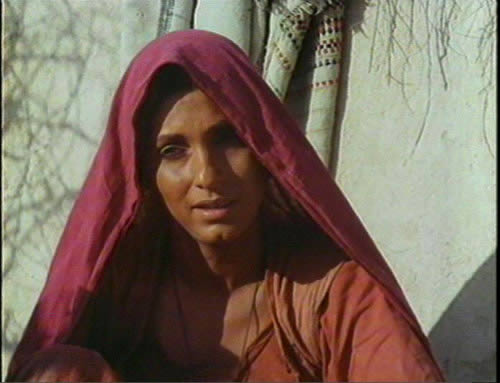

As the narrative begins, the dying zamindar (landlord) or Rajput nobleman of the desert village of Barna (played by a terminally obese Amjad Khan, who indeed expired during the film’s production—it is dedicated to his memory) has been shifted from his mansion to an outbuilding and is performing the rite ofgodaan or gifting a cow to a brahman—a meritorious pre-death ceremony thought to guarantee safe passage across the fearful Vaitarani River of the Hindu Hades. Anticipating his imminent death, and realizing that none of his close relatives are likely to mourn him, he summons a rudaali named Bhikni (Rakhee Gulzar) from a nearby town. While waiting for her client to die, Bhikni temporarily lodges in the modest home of Shanicari (Dimple Kapadia), a widow whose life has been plagued by misfortune. Born on a Saturday (a bad-luck day ruled by the malefic planet Shanichar or Saturn), the ill-omened girl child was blamed by villagers for the untimely death of her father, and then for her own abandonment by her mother, who ran off to join a nautanki folk theatre troupe. The tale of Shanichari’s life, told to the sympathetic Bhikni, unfolds in a series of flashbacks that occupy much of the film.

Shanichari’s early marriage to a gadabout drunkard named Ganju ends abruptly when her husband succumbs to an outbreak of plague at a village fair. She is left with a son, Budhua (played as an adult by Raghuveer Yadav), whom she adores, though she realizes that he has inherited her mother’s penchant for irresponsible wandering. Her poverty is relieved somewhat by employment at the zamindar’s haveli after the master’s son, Lakshman Singh (Raj Babbar) takes a fancy to her. She attends on his spoiled but strictly secluded wife, and periodically converses with her benefactor, who lectures her on social equality and urges her to “look up” into his eyes when speaking to him (rather than averting her gaze as other women do)—these talks (given the evidence of a romantic attraction between master and servant) hover somewhere between idealism and seduction, and eloquently express the constraints on love in a feudal, patriarchal order.

Though it is never clear whether the romance leads to a physical liaison (Lakshman Singh displays a restraint that ethnographic evidence suggests has rarely been the case among Rajput zamindars), it does lead to the master’s gift to Shanichari, one night after a singing performance, of her own house and two acres of land—a gesture that offers her a modicum of financial security within the village. She will need this, since Budhua, after a brief and unhappy marriage to a quarrelsome young prostitute (who aborts their child, Shanichari’s hoped-for grandson), will in turn desert his mother. Shanichari’s painful reminiscences of these trials—throughout which, she says, she has never been able to shed a tear—alternate with scenes in the present, depicting her growing bond with Bhikni. Yet when the latter abruptly leaves her—on the very night of the old zamindar’s long-awaited death—Shanichari learns a secret that unleashes her pent-up emotions and transforms her, too, into a rudaali.

The film’s dialogue, in a rusticized standard Hindi meant to substitute for the Marwari speech of the Rajasthani desert, effectively expresses its stark hierarchies of gender, caste, and class. Villagers never refer to the zamindar and his son by name, but only as “Hukum” (literally “order, command”—identifying them as embodiments of power) or “Sarkar” (“government, authority”). The stereotypic local brahman capitalizes on the villagers’ credulity, demanding stiff fees for ceremonies that will rescue their deceased relatives from hell, and is alternately effusively Sanskritic or (when addressing Shanichari, after whom he secretly lusts) cruelly crude. The spirited heroine, though shouldering debt in order to pay the priest’s fee, fights back verbally and reminds the old lecher of his crimes—although her ability to do so evidently rests to some extent on her own favorable relationship with the zamindar.

Both Rakhee and Kapadia deliver notable performances, yet it is the latter’s portrayal of a slowly maturing woman, whose depth and compassion grow through the routine sufferings of the rural poor in a feudal society, that leaves the strongest impression. And although there are moments when her hard-luck but radiantly aging heroine suggests an updated and art-filmi incarnation of Nargis in MOTHER INDIA, Kapadia’s dignity and conviction, as well as her effective body language and gestures, lift her character far beyond bathos.

[The DVD of RUDAALI marketed by Asian Video Movies Wholesalers Inc. offers a print of decent quality, with optional subtitles that are likewise adequate. None are provided for songs.]